Fall 2019 San Diego City College Student Anthropology Journal

Edited by Elizabeth Cook

Published by Arnie Schoenberg

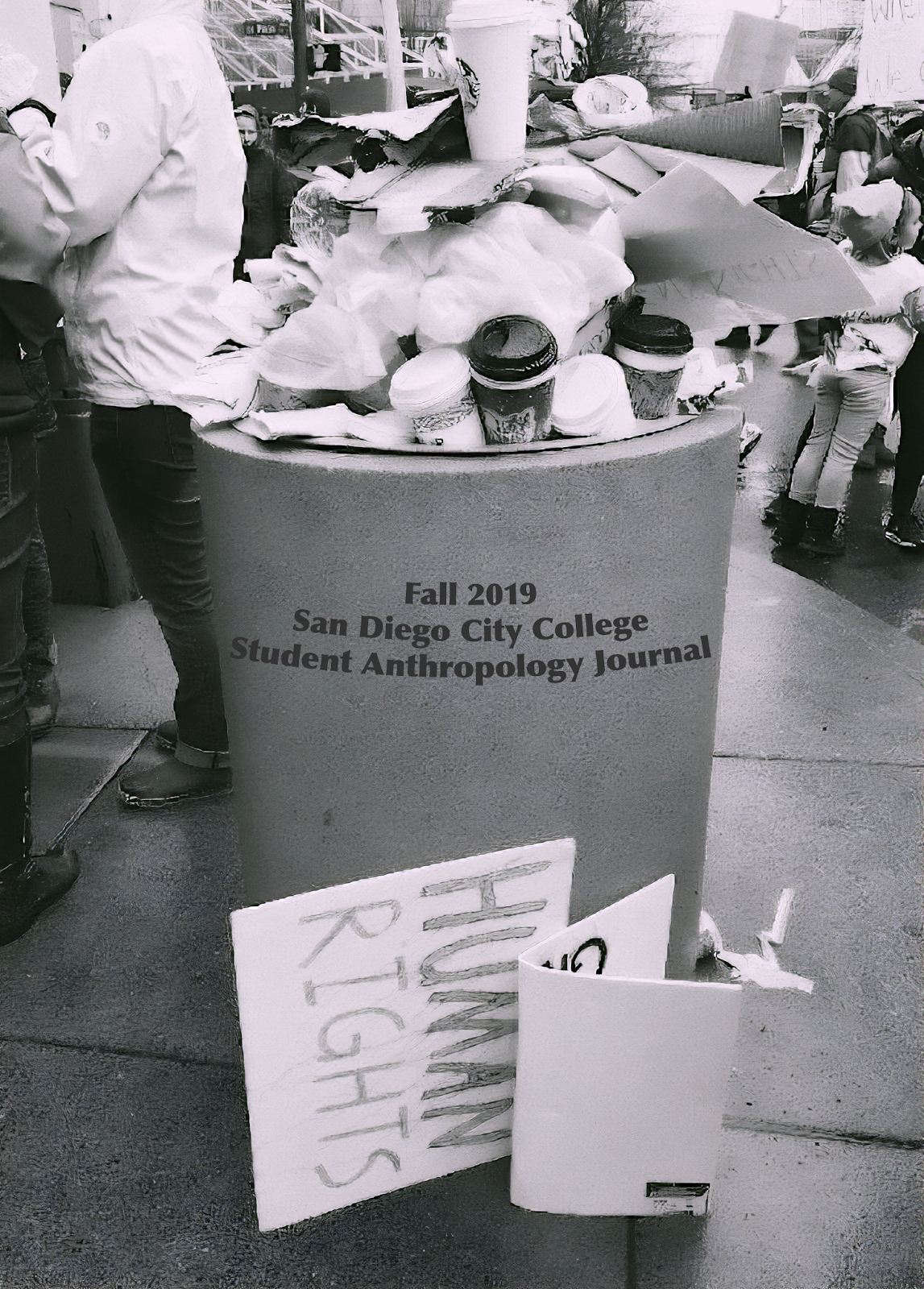

Cover Photo: “A photo of an overflowing trash can with a sign resting on it that read ‘HUMAN RIGHTS’” by Macey Bishop

http://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/journal/fall2019

Volume 3 Issue 2

Fall, 2019

latest update: 6/18/22

Unless otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

More issues at http://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/journal/

contact: prof@arnieschoenberg.com

Genetic modifications have been around for a few decades now, from the food you eat, to the furry, four-legged, good dog you love so much. But when exactly do we draw the line? And at what cost? A designer baby is a genetically modified embryo, typically done to prevent major illnesses within the baby’s future. However, it has become very debatable on where to draw the line between health imperfection, and social/ superficial imperfection. This means humans now have the power to evolve faster than ever. However, not everyone is on board with this power, for multiple reasons. One is that people will use it to create a “perfect” physical appearance, with their baby being a product of a designer world. This is a very expensive procedure, therefore only the very wealthy will be able to achieve this. This is a controversial procedure, and we do not know the outcome of such extreme human-made genetic modifications. This could lead to humanity's doom.

As of 2019, we possess the ability to change a child’s genetic coding from the womb, thanks to the CRISPR (clusters of regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats). Tina Hesman Saey explains the process of how the CRISPR works: “scientists start with RNA. That’s a molecule that can read the genetic information in DNA. The RNA finds the spot in the nucleus of a cell where some editing activity should take place” (Hesman Saey 2018). The CRISPR cuts the DNA, with enzymes that act like scissors, and replaces some nucleotide letters. Adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine are represented with the letters: A, C, G, and T. These are naturally zipped to their opposing nucleotide letter. The CRISPR began as a source of information, to report the pattern of the genomes, and what each trait represented, and was later discovered to have the ability to not only cut and report, but to also edit DNA. This was thanks to American biochemist, Jennifer Doudna, and French professor Emmanuelle Charpentier. With the correct coding, we can form different strands of DNA creating bacteria that could defeat diseases, and more.

Humans now have the power to evolve faster than ever, and this power comes with problems. One is that people might try to create a “perfect” physical appearance, which could lead to stronger discrimination, especially racism and groups of people who do not fit the social beauty standard as it is known within each culture. This could further lead to the lack of opportunity for the poor, given the expense of the procedures. Given that some features are more desirable than others, this will isolate a small group of features within each culture creating a further picked out selection, and the end of natural selection as it is known today.

This procedure has already been performed in China. Twin baby girls were the first two CRISPR babies, “with an edited gene that reduces the risk of contracting HIV. Jiankui He, a Chinese scientist, stated the babies ‘came crying into this world as healthy as any other babies a few weeks ago’” (Hesman 2018). The claim is that the babies came out perfect. However, the only way to know the real results of the CRISPR is to wait, and hope the twins are able to live a long healthy life. Plenty of parents want their biological children to be free of disease traits one or both partners share. A great example of this is Matthew and Olivia, who live in fear of having a baby with the traits they shared.

That term [Designer Baby] has negative associations, suggesting something trivial, discretionary, or unethical. They weren’t choosing eye color or trying to boost their kid’s SAT score. They were looking out for the health and well-being of their future child, as parents should. Matthew was lucky. His was a mild version of DYT1 dystonia, and injections of Botox in his knee helped. But the genetic mutation can cause severe symptoms: contractures in joints or deformities in the spine. Many patients are put on psychoactive medications, and some require surgery for deep brain stimulation. Their kids, Matthew and Olivia were told, might not be as lucky. They would have a 50–50 chance of inheriting the gene variant that causes dystonia and, if they did, a 30% chance of developing the disease. The risk of a severely affected child was fairly small, but not insignificant. My friends learned there was an alternative. They could undergo in vitro fertilization and have their embryos genetically tested while still in a laboratory dish. Using a technology called pre-implantation genetic testing, they could pick the embryos that had not inherited the DYT1 mutation. [Hercher 2018]

Having this technology is a miracle for parents who desire their baby to live a life without internal complications. “Next-generation sequencing improves our ability to detect these abnormalities and helps us identify the embryos with the best chances of producing a viable pregnancy...Potentially, this should lead to improved IVF success rates and a lower risk of miscarriage. Abnormalities in the DNA of embryos account for the two-thirds failure rate of in vitro fertilization (IVF)” (Palmer 2013). The procedure will help solve plenty of future problems with their child. They will not have to see the person they love most in the world suffer in the way they did.

The United States has become more open to experimentation and availability within this field. As for the gene-editing in patients’ cells that aren’t inherited, clinical trials are already underway for HIV, hemophilia, and leukemia. The committee found that existing regulatory systems for gene therapy are sufficient for overseeing such work (Kaiser 2017). The more studies and experiments conducted, the closer we are to creating the possibility of becoming successful at this genetic modification process. However, we still do not know the long term effects on humanity and how it would shift our Anthropological evolution. “In the late 1990s, scientists discovered a gene that is linked to memory. Modifying this gene in mice greatly improved learning and memory, but it also caused increased sensitivity to pain” (Tang, Wei, et al, cited in Simmons 2008). Although this study was conducted 20 years ago, the base example still remains. The side effects could be a defect not so physically visible, or instantly eye-catching, and could later lead to a greater issue in the child’s life.

The procedure could be processed in two different ways. It could be processed as a human germline engineering tactic. Human germline engineering is “the process by which the genome of an individual is edited in such a way that the change is heritable. This is achieved through genetic alterations within the germ cells, or the reproductive cells, such as the egg and sperm” (Wikipedia). This means, sperm, eggs ,or embryos, can change the DNA of future generations, meaning it is changing the human population and its evolution. Or with the alterations of somatic cells, which are the majority of the cells of the body, where DNA is not passed onto offspring, leading to a consistent procedure of gene alteration or having the option to terminate it completely. Therefore, if there are complications with the genetic change or cell change conducted on the designer child, they may or may not be passed along. However, John Travis explained that “the summit’s organizers concluded that actually trying to produce a human pregnancy from such modified germ cells or embryos, either through in vitro fertilization (IVF) with the sperm or eggs or the implantation of an embryo, is currently “irresponsible” because of ongoing safety concerns and a lack of societal consensus” (Travis 2015). In Vitro Fertilization or IVF is the process of fertilization where an egg is combined with sperm outside of the body, in vitro. This procedure can help prevent the transmission of genetic disease from parent to child. Travis later explains that introducing permanent enhancements into the human genome is highly deemed off-limits, but is still up for discussion.

I conducted an informal study on my social media where I asked my followers their opinions on designer babies. The outcome was almost 50-50. It really surprised me to see the outcome, given that my followers are from around the world. However, most of my followers are San Diego natives, creating a slight bias on the answers, given that San Diego is a mostly liberal-minded city. I also asked my followers why they believed designer babies were right or wrong, and here are a few of the results I got: “designer baby is a dystopic term. I’m all for genetic engineering,” - (@jessica) who voted in favor of designer babies. Her answer was very open to the realization in the word “designer” itself. It sounds like an accessory rather than a living, feeling child. Many others were with her when it came to their decision. Many were affected by the term designer baby itself, rather than by the actual procedure. Another popular opinion was that this procedure “leads to ‘perfect’ and ‘inferior’ traits. Like the Nazi Aryans, only the rich can afford it” - (@anonymous). If the genetic modification is, in fact, a modification affecting the physical appearance of the child, then we can indeed be led to this dystopian world, where most will want their child to share the perfect attributes displayed in the media. This will become difficult for lower classes to possess. Finally, one of the most common opinions was that it will prevent disabilities, cancer or any other disease that will negatively affect the child’s health.

A different form of designing babies would be genetic selection. In this case, the selection of traits would be artificial. This is a form of marker-assisted selecting, covering the whole genome that is used. This is typically used to decide which traits are desirable within the egg being fertilized. This process is known as preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), and has been around for more than 27 years. With PGD, fertility clinics remove cells from embryos created through IVF and test the DNA for genetic diseases. However, according to geneticalliance.org “it is difficult to assess success rates for PGD because there is currently little data available. As with most fertility treatments, success depends on many factors, including the woman’s age and weight” (Genetic Alliance, 2019). There are a lot of factors that come into play given that it is such a delicate procedure. This, however, can allow the prediction of the traits of the offspring to an extent, given the variability and selection within each embryo.

As of today, we are already evolving at an exponential rate, compared to previous years. However, with genetic modifications done to embryos, the future of humans will be highly impacted. Whether it is gene selection or gene editing, and whether it is for the greater good, to a straight way to the end of humanity as a whole. Many studies are being presented, from China, Europe, to the United States in order to make this genetic modification a reality. We have successfully achieved the ability to select and modify traits within offspring, and we are successfully genetically modifying somatic cells for therapy reasons. However, if it is decided to allow germlike enhancements and modifications, the results of humanity will be largely affected. It is one of those aspects of life that may be too good to be true, and our idea of a utopia with healthy spawn roaming the Earth can become dystopian quickly. Genetic modifications are still being tested today, but are 100% a reality that we will soon experience as a whole.

Hercher, Laura. “Designer babies aren’t futuristic. They’re already here.” www.technologyreview.com Last modified October 22, 2018. Accessed October 11, 2019. https://www.technologyreview.com/s/612258/are-we-designing-inequality-into-our-genes/

Saey, T. H. 2018. "Chinese Scientists Raise Ethical Questions with First Gene-edited Babies." Science News

Saey, Tina Hesman. 2017. "Explainer: How CRISPR Works." Science News for Students. Accessed November 15, 2019.

Kaiser, Jocelyn. 2017. “U.S. panel gives yellow light to human embryo editing”. Sciencemag.org. Last modified February 14, 2017, 11:00 AM. Accessed October 11, 2019. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/02/us-panel-gives-yellow-light-human-embryo-editing

Palmer, Chris. "Next-Gen Test Tube Baby Born A baby has been born using in vitro fertilization aided by next-generation sequencing of embryos for genetic abnormalities." The Scientist » The Nutshell. Last modified July 10, 2013. Accessed October 11, 2019. http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/36454/title/Next-Gen-Test-Tube-Baby-Born

Travis, John “Inside the summit on human gene editing: A reporter’s notebook”.Last modified December 4, 2015. ScienceMag.org. Accessed October 11, 2019 https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/12/inside-summit-human-gene-editing-reporter-s-notebook

Simmons, Danielle. 2008. “Genetic Inequality: Human Genetic Engineering” Nature Education. Accessed November 15, 2019 https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/genetic-inequality-human-genetic-engineering-768/

Wikpedia. “Human germline engineering”. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_germline_engineering

Hello, my name is Lizbeth Sanchez, I have two jobs and go to school full time. Have you ever seen a movie, where a lady is an overachiever and always looks like she's going crazy? That's the story of my current life. I am a business major with a strong passion for psychology and sociology. I love taking classes on subjects people are typically passionate about in order to understand them at a deeper level. One of my jobs is to be a "love" coach, but I see it more as a life coach in general. Therefore it is ideal to become aware of different people's interests and try to put myself in their shoes, to be able to find and speak with commonalities. This will help me understand them at the core level and help me find what they're looking for in order to help them from a standpoint they're comfortable with and understand. I am also a part-time licensed barber in Downtown, San Diego, so I get to meet people and learn from their experiences. Thanks to barbering, I have a greater understanding of my long-term goals, given that I get the opportunity to talk to many different people with a variety of career paths. This has helped me become more and more aware that the path of social service that I am taking is exactly what I want.

Indigenous cultures have been influenced by Western Europe for hundreds of years. Women of these indigenous communities have faced challenges when attempting to integrate with Western Europe. With this paper I will examine the Navajo women of Utah and the Inuit women of Greenland during the late twentieth century. These women faced struggles that required them to work harder than their white peers and to make life-changing decisions that would require them to leave their homes if they wanted to find a different life.

First, I will consider the book Saqqaq: An Inuit Hunting Community in the Modern World written by Jens Dahl (2000). Dahl wrote this book after observing the community of Saqqaq during 1980 and 1981. He lived among the people and recorded their way of life. He added to this experience information compiled from historical archives, newspapers, personal memories, and events that have taken place after that time resulting in his book (Dahl 2000, 4).

The settlement of Saqqaq is a small village on the western coast of Greenland. It sits on a sunny slope of a mountainous peninsula. In 1997, the village had a population of 212 with the majority being indigenous Greenlanders (Dahl 2000, 24-5). The people here speak their native Inuit language, Greenlandic, with Danish being the secondary language.

The village is a hunting village. The men hunt and the women traditionally take a supporting role. The men provide food and materials for the people of the village. This is their first priority. The women support this by processing the meat, taking care of the household, and finding salaried employment to support the family financially (Dahl 2000, 186). This traditional way of life has left women living here at the end of the 20th century with little motivation to stay in the community. Young women began looking at opportunities outside of the community, and the parents of these girls encouraged them to continue schooling in Denmark.

Janne Flora, a researcher, wrote an article about these students who travel to Denmark for education. She asked why they left and what they hope to accomplish. These Greenlanders reported that they are embarking upon higher education not for social mobility but for a civic duty, for the sake of Greenland’s future (Flora 76). These young women are creating choices in which they can stay in Europe and pursue a different life, return to their villages to run the processing plants, schools, and institutions, or stay in Greenland to embrace the traditional way of life. The men have more limited options. They do have the same educational opportunities as women, but the families encourage young men to stay with their parents to hunt (Dahl 2000, 38). If young men leave they jeopardize elders’ access to seal and whale meat, a commodity that they view as essential (Dahl 2000, 155).

Greenland has had a very isolated history. It has been a colony of Denmark since the early 18th century and ruled over by the Danish until the 1970s. At that time the people of Greenland began governing themselves with the establishment of Home Rule. Home Rule gave Greenland the right to legislate some of their internal policies. Denmark maintained full control of external policies, which has resulted in a complicated history (Wikipedia). For the purposes of this paper I will focus on the policies of education and gender. Greenlanders are Danish citizens. They have a right to attend schools in Denmark and in the 1990s the only option for higher education was to leave Greenland and attend school there (Flora 73).

The primary school in Saqqaq is one of its most important institutions. The children are required to attend from six years old until they finish ninth grade. For students that want to continue schooling they then have to attend a boarding school in the larger town of Ilulissat.

In contrast to these ideas, I will now look at young Navajo women living on a reservation in Utah in the late 20th century. Donna Deyhle (2009) wrote her book Reflections in Place: Connected Lives of Navajo Women after conducting ethnographic research on the reservation. Deyhle took a deductive approach to her ethnographic research. She selected a problem and let the problem guide her research (Brown 2017, 10). She studied the Indians living on the reservation to find out “Why do Navajo youth leave school?” and “What factors help Navajo students succeed in school?” (Deyhle 2009, xi). Deyhle lived on the reservation in 1984 and then continued her research for 25 years afterwards (Deyhle 2009, x). She followed the lives of three Navajo women. She first met them while they were in high school and followed them into adulthood, as they had their families and jobs. One of the first problems Deyhle discovered was the youth largely had uneducated parents (Deyhle 2009, 20). Navajo students were not allowed in public school until the 1950s (Deyhle 83). Before that they attended schools on the reservation and only obtained a limited education. The families on the reservation have a history of leaving to find work and a better life, only to return again when they are not successful. On the reservation they can rely on a traditional way of life as sheepherders (Deyhle 2009, 68).

Jan and her family had just moved back to the reservation after living in Moab for eleven years. Scattered throughout these years were times of unemployment when the fluctuation of uranium prices in the world market forced plants and mines to lay off workers. Ernie had told me, “We decided to return to being Navajos again. We had Elizabeth’s mother’s flock of sheep, so we decided to learn to be sheepherders again!” He spoke contentedly about their life. “We don’t have electricity. And we don’t have electric bills. We haul water, and we don’t have water bills. And out here we don’t have to pay for a [trailer] space. [Deyhle 2009, 68]

At this time in 1984, fifty percent of Navajos living on the reservation were living without water and electricity (Deyhle 2009, 69). They lived in small homes. The roads there were unpaved.

Navajo women are systematically denied equal opportunities at all levels of schooling and in the workforce. This has created an impoverished community. Deyhle has followed Jan, a young woman on the reservation, through her schooling. She observed the classes offered to the children from the Navajo Reservation and the oppression that occurred. Jan was interested in taking higher-level classes, but “Navajo students saw survival strategies in the high school as enrolling in classes where fellow Navajo students would surround them, minimizing racial assaults in mainstream classes” (Deyhle 2009, 97). Instead she took classes in jewelry design, driver education, history, welding, accounting, and health. All without a clear career path. This trend continued when Jan moved onto college. The Navajo youth were encouraged to seek terminal degrees in vocational areas (Deyhle 2009, 108). It is known that “political economies constrain people’s choices and define the terms by which we must live and while humans are inherently creative, our possibilities are limited by the structural realities of our everyday lives'' (Lyon 20). These ideas were clearly visible in the lives of young Navajo women. They face constrained choices and limited possibilities.

Deyhle observed that Navajo people had limited choices in their education resulting in limited job opportunities. The local community college offered almost 100 courses and two-thirds of these were in vocational or technical areas (Deyhle 2009, 108). The Navajo Nation also co-sponsored special vocational programs designed to fill immediate job needs in marina hospitality, needle trades, building trades, sales personnel training for supermarket employment, pottery trades, office occupations, restaurant management, and truck driving (Deyhle 2009, 108). An instructor she interviewed explained the problem with this mass training for limited jobs.

“We trained forty or fifty people at a time to run cash registers. That’s good. But how many stores around here are going to hire all those people? They’re training for limited jobs. Why send everybody to carpenters’ school? In this small area we have tons of carpenters. Why teach them all welding? You can do it at home, but how many welders are there in this area? Probably every other person is a welder” [Deyhle 2009, 109].

During the 1980s at the community college, Navajo youth and adults earned 95 percent of the vocational certificates (Deyhle 2009, 109). Navajos and whites had equal population numbers in the community, but whites held over 90 percent of the professional and managerial jobs. White teachers held over 85 percent of the teaching positions. Deyhle, after following 537 young women for 10 years, found an unemployment rate of 67 percent and of those employed only 27 percent were employed full time (Deyhle 2009, 110).

With the data that Deyhle was able to collect she concluded that Navajo women wanted jobs in the community. Women who had higher degrees obtained the few professional jobs available. Navajo women had very limited access to managerial and professional level work (Deyhle 2009, 109). Due to the racially defined job ceiling, limited vocationalized training in high school and college, and the family pull for them to stay in the area, most women were unemployed or had low pay service level jobs (Deyhle 2009, 110). Most of the women remained in their home communities, received some kind of federal assistance, and pursued any kind of job available (Deyhle 2009, 111).

When comparing these two groups of women in these indigenous communities we can see many similarities and just as many differences. Throughout both communities we see the value that the young women bring to their families. In the Greenlandic community it was observed that women have access to an equal education but have limited options to pursue a higher level of education. It is expected of them to travel away from home to get this education. While they are doing this they have pride in their culture and are not expected to leave it behind. Many have said that they chose to study away from home in Denmark for the sake of Greenland’s future, rather than solely for their own sake (Flora 76).In contrast the women living with the Navajo Nation are simply doing what they can to survive. They leave the reservation to find jobs and return again when times are hard. Their education choices are limited by how hard they want to work and what they can endure for equal access to the classroom. If they are lucky enough to find a good education they are limited by racial discrimination and lack of work when looking for a career near their homes. To find success they must leave the reservation.

For the success of their families these women must raise children and work outside the home to bring in extra money. The men in both communities expect the women to contribute to the household, while at the same time they must continue to perform the traditional roles of their native people. The women in the Navajo Nation are slowly leaving their traditional roles behind at the cost of losing parts of their culture. The women in Greenland are not pressured as much to set aside their traditional roles. The men in Greenland are still simply hunters and the women are still needed to process the meat and skins.

These two books were written at the end of the 20th century, before the age of the internet, before everyone had access to telephone, water, and electricity. In the past twenty years as these conveniences are available and provided to all I wonder how these communities have changed. Have the Greenlanders held on to their hunting lifestyle, with the men providing the meat and the women providing everything else? On the Navajo reservation has the gap between whites and Indians grown smaller?

Brown, Nina. 2017. “Doing Fieldwork: Methods in Cultural Anthropology.” In Perspectives: An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology. Edited by Nina Brown, Laura Tubelle de González, and Thomas McIlwraith. American Anthropological Association. Accessed October 28, 2019. http://perspectives.americananthro.org

Dahl, Jens. 2000. Saqqaq: An Inuit Hunting Community in the Modern World. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Deyhle, Donna. 2009. Reflections in Place: Connected Lives of Navajo Woman. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

Lyon, Sarah. “Economics.” In Perspectives: An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology Edited by Nina Brown, Laura Tubelle de González, and Thomas McIlwraith. 2017. American Anthropological Association. Accessed: October 26, 2019. http://perspectives.americananthro.org

Wikipedia. “History of Greenland”. Accessed October 28, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Greenland#Home_rule

My name is Sarah Rice. This is the start of my second year of community college. I'm returning to school later in life to keep up with my kids who are now also attending college. One of my daughters is majoring in anthropology and I would like to be able to have discussions with her on the topic. I have always been a housewife and now as the kids are older and don't need so much of my time I decided to explore college. I have extensive experience in living life, raising kids, and helping with homework. My goals are to learn all I can. I don't have any professional goals at this time. As my husband and I head towards retirement we are looking forward to travelling and grand-kids.

When it comes to “tying the knot” family customs and traditions vary throughout different cultures. In this ethnology I will focus on these practices using two distinct tribes. The Ese Eje, a community of people who reside in the Amazonian forests of South America, and the Kgatla tribe of the Bechuanaland Protectorate whose territory lies between the Molopo River and the Zambesi River in South Africa. I will also make some direct connections with the “Family and Marriage” chapter in the An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology textbook regarding the Kgatla tribe. More specifically I will focus on the different ways and options these tribes have available when choosing to get married.

Among the Esa Eje people of the Bolivian and Peruvian Amazon there are two options when it comes to marriage that are traditionally accepted. Couples can either make their marriage public which is preferred by the tribe, or they can choose to keep their marriage secret allowing the couple to make their own decisions by keeping family influences out of the marriage. Typically, it is young couples who decide to keep their marriage secret. In the Esa Eje community family is greatly valued and the immediate family is very involved in the lives of a recently married couple. For example, when a couple marries, the husband moves into the home of the bride’s immediate family right away.

In the Kgatla community secret marriages would never be an option. Traditionally, parents on both sides of the family would make the decision of whom their offspring would marry. In more modern times, due to Western influences, their offspring’s opinions are greatly considered in the decision making. Tribal law actually states that both sides of the family have to conduct formal negotiations before the wedding ceremony takes place. This being said, unlike the Esa Eje community, the Kgatla people would never consider secret marriages an option technically speaking it would be against tribal law to conduct such an act.

In India some practice a kind of modified arranged marriage that allows potential couples to meet and spend time together before agreeing to a match. Although arranged marriages still exist, love matches are increasingly common. As long as social requirements are met, love matches are accepted by the families involved (Gilliland 2017, 10). East Indians call it “marriage meet”, the Kgatla tribe doesn’t have a specific name for it but the practices are very similar. Although parents make the final decision whether a marriage takes place or not, a groom has the opportunity to express his interest in a potential bride. The potential couple’s desire towards a potential mate isn’t always met by the parents. This could be due to several things, including social status.

This practice of “modified marriage”, in a sense, could be compared to secret marriages among the Esa Eje Amazonian communities. In a secret marriage the couple has the ability to get to know their partner before they decide to commit to marriage or make their marriage public. Unlike the Kgatla where marriages are focused not on love but on financial stability, the Esa Eje are allowed to choose a partner they desire. The separation of a married couple is greatly shamed among the Esa Eje and it is often not an option. If a couple is secretly married and decides to separate, they will not have to face the shame of their tribe. Most likely, due to their marriage being secret, no one will notice they were even a couple in the first place. This of course is not the same as the modified marriage practices in India. But it does give couples the opportunity to get to know each other before committing to marriage and in the Esa Eje community a chance to avoid shame from their tribe.

The main priority in an Esa Eje marriage is collaboration between partners. Their marriage isn’t judged or deemed successful based on the couple’s happiness. It is the financial stability and success attained by the couple once married that determines whether the marriage is a successful one or not. In a public marriage the husband immediately moves his belongings, usually not very many, into the bride’s household together with her parents and other siblings. It is during this time the husband has to demonstrate his willingness and ability to provide for his wife. The bride’s family gets a chance to make sure the new addition to the family has what it takes to provide for his own household when the time comes. He proves himself by hunting, fishing, and working the field providing not only for his wife during this time but her entire family as well.

The Kgatla tribe, just like the Esa Eje, also prioritize financial stability when contemplating a marriage. The parents of a potential couple are in charge of arranging a marriage but not before they verify the individuals are financially compatible. As mentioned above the son’s opinion is greatly valued when he shows interest in a potential spouse. Although his opinion is taken into consideration, the parents have the ultimate say depending on financial compatibility whether the marriage takes place or not. People are expected to marry within religious communities, and to marry someone who is ethnically or racially similar or who comes from a similar economic or educational background (Gilliland 2017, 10).

In my opinion, American culture has one of the most diverse definitions of what family and marriage should be. In recent times we’ve experienced a big movement in the LGBT community regarding rights when it comes to creating a family and getting married. The traditional way of what a family or marriage should look like is slowly taking a turn. Today a marriage between the same gender is widely accepted. A family with two fathers or two mothers isn’t uncommon. Wedding ceremonies could simply be the signing of a document stating two individuals are legally married. Weddings could also involve spending thousands of dollars and inviting family and friends.

The concept of family and marriage is universal; it is practiced in every single culture. The ceremonies differ depending on the traditions each community is accustomed to. Although there are many differences through cultures in their traditions and customs, there are some similarities. Economics and religion play a big factor in most cultures when deciding to start a family. There aren’t any set biological rules that dictate how a family should act or start, but there are certain cultural expectations. Time changes cultural customs and traditions, new ideas about family also adapt to new circumstances (Gilliland 2017, 18).

Daniela Peluso. The Anthropology of Marriage in Lowland South America: Bending and Breaking the Rules. Edited by Paul Valentine, Stephen Beckerman, and Catherine Ales, 2017

Gilliland, Mary Kay. 2017. “Family and Marriage” In Perspectives: An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology. Edited by Nina Brown, Laura Tubelle de González, and Thomas McIlwraith. American Anthropological Association. http://perspectives.americananthro.org

Good evening everyone my name is Jesus Cabrera, I am a fulltime student this semester taking a whole fifteen units. I am a veteran and a part time reservist stationed out of Naval Base Coronado. My discharge date was in June of this year, during my active duty time I served aboard two naval ships stationed out of Norfolk, VA. My rate in the Navy and in the reserves is Engineman, our duties consist of operating, completing preventative maintenance, and repairs on diesel engines. Upon completion of my time in the military, I realized I had to search for a job in the real world. I was unclear of what I wanted to do next the only thing I was certain of, engineering was not a field I was interested in pursuing as a civilian. After some time, I decided to pursue a career in law enforcement hoping to continue serving from my hometown. I am currently working towards an Administration of Justice degree, while in the hiring process for several police departments.

“A photo of an overflowing trash can with a sign resting on it that read ‘HUMAN RIGHTS’” by Macey Bishop

“Race is fake!” “We’re all one race, the human race.” “Well, I’m not really white, I’m Italian!” These are just some of the phrases that are common in conversations surrounding race in the United States- a diverse country with tense racial politics. When filling out surveys, many Americans struggle with the question of race. There is a similar reality in Brazil. Like Americans, some Brazilians feel that their racial identification fits neatly into a survey box, while others reject the idea entirely. So why do so many people have different understandings of what race is? In order to explore this topic, one must start at the origins of race and understand how it has been socially constructed across cultures. In order to do so, this ethnology will focus on the United States and Brazil, two countries that–although both part of The Americas–have vastly different ways of understanding and organizing race.

It is important to begin by defining the differences between race and ethnicity, as they are used interchangeably at times but are not the same thing. In the Encyclopedia Britannica, it says that in the United States, the term “race”, “generally refers to a group of people who have in common some visible physical traits, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and eye formation” (Wade et al., 2019). The Oxford Dictionary defines ethnicity as “the fact or state of belonging to a social group that has a common national or cultural tradition” (Ethnicity). The key distinction between race and ethnicity is that race is solely based upon how someone looks to someone else, while ethnicity refers to someone’s genetic makeup in regards to the region they, their family, or their ancestors are from. While this ethnology is on race, ethnicity also must be examined as these two different concepts often go hand-in-hand.

A scholar named Charles Taylor said that humans experience a natural desire to claim their ethnic and racial diversity through recognizing these identities (Sansone 2003, 3). However, if identity is born out of the existence of human-made borders, how can this be true? L. Sansone writes that “If ethnic identity is not understood as essential, it then has to be conceived of as a process, affected by history as well as contemporary circumstances, and by local as well as global dynamics” (Sansone 2003, 3). Here, “ethnic identity” is an all-encompassing term that is used to refer to how one defines their own race and ethnicity. Viewing ethnic identity as something affected by both history and the current day is vital. This would allow space for ethnicity and race to be more of a spectrum and mixture of ways in which one thinks of themself, while still acknowledging that it can have tangible and oppressive realities.

Sanson continues by focusing on Brazil specifically. He works on breaking down what race is through asking questions.

Striking a new balance in this dilemma could make a major contribution in addressing the key questions born by ethnic studies in Brazil: why is it that Brazil has a history of racism against black people, “indios”, and immigrants (mostly those of non-European origin), while the narrative of ethnic mixture, supported by the reality of miscegenation, has proven more powerful? Why is it that in so many other contexts race and ethnicity- whose dark side takes the form of racism and whose more generally accepted side is nationalism- and the issue of cultural integration have throughout history and in recent years sparked riots, movements, and wars, yet in Brazil they have failed to mobilize the same degree of collective emotion and action? [Sanson 2003, 4]

When folks from elsewhere in the world imagine someone from South America, they may picture someone with mainly light brown features. As the reader, the person you may be imagining would have an ethnicity of “South American”, specifically one of a certain country, but their race would be what you create in your mind. This imagined person’s race would be the physical attributes they have. There are stereotypes that exist for both ethnicity and race. Imagining a South American person as “light brown” is a stereotype, but it also erases Afro-Latinx populations and denies the possibilities of a racial and ethnic spectrum in countries that are home to people of color. Sansone mentions a “hidden hyphen” that exists in Brazil when defining one’s ethnicity. This doesn’t allow folks to embrace multiple facets of their ethnic identities and call themselves Afro-Brazilian, Lebanese-Brazilian, and so on (Sansone 2003, 5). Sansone continues noting that the social construction of race in Brazil differs depending on the context. These hyphens allow marginalized people to claim their marginalized identities, seek meaning in them, and form connections with others who identify in the same way. If someone that appears white is simply “Brazilian” while someone that appears black is also just Brazilian, the black person may not then be able to fully call out the injustices they face. To the white Brazilian experiencing many social privileges, they might claim that they’re all “just” Brazilian, so what’s the issue? The existence of race-based oppression creates the necessity for the oppressed to have language for what they are experiencing, and how they are being set apart.

Although Brazil and the United States now have different concepts of race, these countries were born in similar ways. Both countries were created through European colonialism and used enslaved African people to work plantations. Additionally, both countries have had many immigrants since then (Garcia 2017, 13). In Brazil, rather than describing someone’s “ethnicity”, meaning their genetics, people are described in “types”. These categories are vast, there are words for people with light skin and blonde hair, with curly blonde hair and green eyes, with dark skin, and dark straight hair, the list goes on (Garcia 2017, 13). In the United States, someone’s complex appearance often gets watered down to skin color, or a defining “non-white” feature.

Let’s rewind a bit though. The concept of race first appeared in American history in the seventeenth century. As Leda M. Cooks stated, this was “when the colonists began to identify themselves as ‘white’ in distinction from the Indians whose land they were appropriating and the black slaves they were enslaving” (Cooks 2006, 3). In the United States, race was first conceptualized not out of unique self-identity, but rather out of the desire to prove one's difference from another. In the U.S., race began as “white”, and everyone else; again, centralizing “white” and other appearances as “non-white”. Later on, in 1790, the first law was passed by congress to control the access of immigrants to citizenship. This made it so that only a “free, white, person” had the right to naturalization. The distinction between ethnicity and race in the U.S. appeared around 1930, when the census never racialized European immigrants. It recognized them by their nation of origin. However, Mexican and Asian folks had specific racial categories (Cooks 2006, 3).

While all people of color in the United States experience oppression and different kinds of disadvantages, black folks have a “special position”, as Cooks puts it. This special disadvantage, according to Cooks, is “slavery, Jim Crow, ghettoization, and, most recently, massive incarceration” (Cooks 2006, 8). Cooks claim that there is a conclusion that American society would be better off if black people could create their own self-identity through various ethnic groups, rather than one race. However, for many, this is impossible. How can folks who were forced to go to the U.S. as slaves know what country their ancestors were once from? Despite this, a black panethnicity of “the Black Diaspora” has gained traction. Diaspora is “the dispersion of any people from their original homeland” (Diaspora).

Although Brazil sounds as though it is more racially progressive or has achieved a greater level of equality than the United States, many Afro-Brazilians claim differently. Afro-Brazilians make up about half of Brazil’s population, and only 2 percent of university students. There are large economic disparities between Afro-Brazilians, those of European descent, and everyone else on that spectrum (Garcia, 14). A common expression describing the racial make-up of Brazil and the U.S. is “the United States had two British parents while Brazil had a Portuguese father and an African mother” (Garcia, 14). In the United States, during colonization, marriage between colonizers and native people, as well as African people, was rare. However, in Brazil, Portuguese colonizers often had relationships with African women. This created a wide range of appearances in the next Brazilian generations to come. It is said that “The United States has a color line, while Brazil has a color continuum” (Garcia, 13). In the United States, if you have curly hair and tan skin you may immediately be categorized as black, even if you are white and a quarter African, or any other ethnic makeup. However, in Brazil, a small sunburn may cause someone to be categorized as a different “type” until that sunburn goes away. Additionally, the fluidity of race in Brazil goes as far as someone being considered more white when they have more money (Garcia, 14). This means that a Brazilian's racial categorization can change throughout their life depending on their socioeconomic status, even though they have looked the same the whole time. In the United States, race is so heavily reliant on visual markers and stereotypes that something like socioeconomic status does not change one’s race.

These differences may not be so prominent after all though. Brazil and the U.S. have very similar systems of five official racial categories that are decided by the government and appear on censuses and forms. In both countries, a large majority of citizens and people that live in these countries reject these categories. Brazilians' rejection of these categories is what birthed all the different “types” of people. In the United States, this rejection has taken form more as a reclamation of offensive words or oppressive language, rather than creating new categories all together.

If these two countries were created through almost the same means, perhaps they are not actually that different. Were small differences in the Portuguese and British colonizers enough to create different realities for similar people today? Or, do humans bend toward racism and the oppression of people of color, and simply have different ways of practicing that and covering it up? Based on Sansone, Cooks, and Garcia’s findings, it appears that Brazil has claimed its use of the racial spectrum as sufficient enough as far as racial equity goes. However, the realities in the United States and Brazil are similar: people of African descent and other people of color are at a large disadvantage. Perhaps, it begins with the white man believing he could travel to anyone’s land like it was his own, and use anybody for his advantage. Perhaps, if the white man had stayed put and minded his own business, there would be no conversation about the social construction of race, perhaps it would not even exist.

Cooks, Leda M. “Not Just Black and White: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity in the United States (Review).” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 9, no. 2 (2006): 344–47. https://doi.org/10.1353/rap.2006.0038.

“Diaspora: Definition of Diaspora by Lexico.” Lexico Dictionaries, n.d. https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/diaspora.

“Ethnicity: Definition of Ethnicity by Lexico.” Lexico Dictionaries, n.d. https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/ethnicity.

Garcia, Justin D. 2017. “Race and Ethnicity.” In Perspectives: An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology. Edited by Nina Brown, Laura Tubelle de González, and Thomas McIlwraith. American Anthropological Association. http://perspectives.americananthro.org

Sansone, Livio. 2003. Blackness without Ethnicity: Constructing Race in Brazil. New York: Palgrave

Wade, Peter, Audrey Smedley, and Yasuko I. Takezawa. “Race.” Encyclopædia Britannica. October 18, 2019.

My name is Macey Bishop, I am a full-time student and a full-time worker at an ice cream shop, as a nanny, and on-campus at City College. I went to the University of Portland for a year and a half after high school until I decided it wasn’t for me and moved to San Diego last year. I am now working toward a Psychology degree in hopes of becoming an art therapist, a professor, or really anything relating to teaching and encouraging positive mental health practices. Coming from a preppy private university, I thought that I would feel behind in school because I “should” be graduating this year. However, my time at City College thus far has shown me that you can be a student at any age, and there is no set timeline of when to get your studies done.

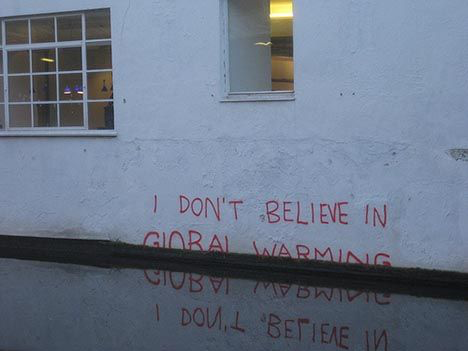

“Climate Change: Too hot to handle” 2009 by John Englart https://www.flickr.com/photos/takver/4178690408 CC BY-SA 2.0

Do you expect anyone to change the way they live in order to inhibit the end of Earth’s time? Many researchers and climate activists answered in the affirmative saying: "It’s not too late." Anyone can make subtle changes in their life that can make a huge difference for our planet. Despite all its crises, the world is not lost, and people must turn to already existing ideas about climate protection, agriculture and energy production — and make use of them (Kürten 2019). "So, by all means, let’s talk about how urgent action is, and imagine the worst results of not acting, but let’s be sure to tell stories that lower the barrier to taking action, too, individually and collectively" (Christensen 2017).

The tunnel vision doomsday narrative around conspicuous consumption creating ecological devastation, ultimately leading to the destruction of our world that is being portrayed in the media today is creating a sense of fear and hopelessness that leads to inaction. Without providing a more balanced optimistic view that includes hope being part of the story, society is left with depression, panic, guilt, shame and becomes disengaged, with some even denying that the problem exists. I reference scientific research, articles, quotes by experts, and real life examples that will validate my conclusion that a gloom and doom narrative for climate change on its own creates inaction by the general public.

“I don´t believe in global warming.png” by Matt Brown 2009 CC BY 2.0

Almost all the stories reported in the news today that refer to climate change and globalization rely on painting a picture of tragedy and hopelessness. These “fear, misery, and doom headlines and articles” (Boykoff 2012), very rarely use positive words such as “strong,” “capable,” or “empowered” to describe the people affected, rather portraying them as helpless victims instead (Adams 2008).

Journalists are supposed to take the role to present the unbiased truth and report it so that the public will be aware and can take action; "reporting just the doom and gloom about climate change is insufficient” (Arnold 2018).

Over the past 50 years multiple scientific and environmental scholar studies have repeatedly outlined the dire consequences of our global climate crisis, and while nobody disagrees or "disputes the validity of the information," almost all responses were "condemned as alarmist and overreaching" (Mattis 2018). "Calling attention to the impacts of climate change is essential if you are a journalist covering climate change. But if how people are responding, individually and collectively, is framed out, the whole story is not being told" (Arnold 2018).

In California, we continue to hear about “the big one” – the massive earthquake coming soon, with the California Earthquake Authority (CEA) touting notices to buy earthquake insurance, emergency kits for preparedness and even launching the first statewide early warning earthquake alerts system earlier this year.

David Wallace-Well's latest book, The Uninhabitable Earth, goes into scary detail, reading like an apocalyptic horror, on how our lives will be affected due to climate change (Riederer 2019). Have we become so accustomed to hearing bad news that we have unconsciously created a doom barrier?

It’s no surprise that people can’t process the truth about the climate crisis and instead construct defense mechanisms against it. In twenty years, what now registers as an extreme heat wave will likely be the norm. By 2045, more than three hundred thousand U.S. homes will be lost to encroaching oceans; by 2100, a trillion dollars’ worth of real estate will be lost in the U.S. alone. As atmospheric carbon levels rise, plants produce more sugars and fewer nutrients—by 2050, vegetables will be turning into junk food. There’s a huge overlap between things that wreak havoc on the climate and things that serve a materialist version of the good, comfortable life: meat-eating, air-conditioning, air travel. [Riederer 2019]

“It’s a basic part of being human that our minds frequently deal with competing interests—that’s how defense mechanisms are formed,” Margaret Klein Salamon, a clinical psychologist and founder of a climate-advocacy organization said. "The daily apocalyptic talk of crisis, catastrophe, and tipping points seems to have clouded the senses of many people" argues Felix Steiner in his opinion article on The eco-warriors of climate protection. Wallace-Wells hits this same note in his book, too, writing: “We seem most comfortable adopting a learned posture of powerlessness.” As uncertainty and denial about climate have diminished, they have been replaced by similarly paralyzing feelings of panic, anxiety, and resignation (Wallace-Wells 2019).

And, John Christensen, in his article, "Climate gloom and doom? Bring it on. But we need stories about taking action, too", surmises the same: “Dystopian visions are easy to conjure these days; they come with scientific probabilities. The second part of that communication strategy – making a compelling connection to how we can act, individually and collectively, to avoid the worst consequences of climate change when so much of our lives depend on fossil fuels – is the really hard part” (Christensen 2017).

While the media continues to use a repetitive message of pessimism in climate change reporting, there are also other climate change stories that tend to rely on the so-called false balance: journalists, using their traditional norm of balance have introduced a false equivalence into coverage by adding a contrarian point of view (Boycoff 2004). A good example of this is in reporting the story of Newtok, Alaska. Arnold writes that she was "a national broadcast correspondent reporting on environmental conditions" and the focus of the story was on a remote community of roughly 400 indigenous people in Northwest Alaska. Their land is "losing forty to a hundred feet of coastline a year to erosion, and sinking because of 'permafrost' that is no longer permanent, the direct result of a warming climate." Arnold continues, "In this example, many facts have been repeatedly told nationally and internationally: the community is threatened because of a warming climate." Experts are suggesting that the residents of Newtok need to be relocated "but the facts that are left out or downplayed, may be just as important to report: the community has been in the process of relocating for more than ten years" (Arnold 2018). This is a perfect example of how the media has swayed the narrative. At the same time, journalists described local communities as “endangered,” “threatened,” “facing losses” and “incapable of responding” in the wake of global warming with text, images and writing style specifically chosen to set the scene of environmental disaster -- which may not be the case, according to Lucy Adams, as interviewed by Arnold in Kivalina, Alaska. These indigenous locals don't want to relocate, but would rather rebuild and repair their community to prepare for the inevitable. She further sums it up by saying “If people in the Arctic weren’t good at making the best of what they encounter, there wouldn’t be people in the Arctic.”

Not all humans created this problem. "The indigenous did not exploit natural resources to the point of collapse; they honored and respected other species and their place in our global ecosystem. They considered more than quarterly earnings; they considered the consequences of their daily actions and looked forward toward the preservation of life for a minimum of seven generations of their people." [Mattis 2018]

“Time To Act Climate Change London Protesters Creative Commons” by David B. Young 2015 CC BY-NC 2.0

Mattis, along with many others, point to climate change being a consequence of greed. She further elaborates that people don't dispute that there is a global climate crisis but they are reluctant to change because they are focused on chasing the dream of becoming rich and the "mega-rich generated their massive fortunes by exploiting the environment, so clearly they are averse to change."

The truth is that the public has not taken action because no one dares to explain what to do, and no one dares to explain what to do because what to do inevitably involves radical changes to the daily lives of the majority of people in the western world, most especially the richest among us who contribute the most to all of our ecological calamities. But even more importantly, no one with money, power, and influence dares to walk the walk when it comes to personal environmental action. [Mattis 2018]

"Our current capitalist economy creates a culture of consumerism, where our happiness is measured by conspicuous consumption" which ultimately can be traced back to exploiting the environment at all costs (Schoenberg 2019:8.1).

Our modern technological, consumerist, lifestyle must be massively curbed. Changes that would help the environment and changes that would bring more social justice go hand in hand, because it is precisely the industries, occupations, and lifestyles of the rich that create the enormous environmental, economic, and social crises. [Mattis 2018]

"Market forces that enrich the wealthiest not only permit, but demand that food goes wasted rather than to the hungry, that clothing is destroyed rather than worn by those who have need for it, and that homes are left empty rather than housing the millions of homeless and marginally-sheltered around the country" (Mattis 2018). As a consequence, climate change, extinction of species, ecosystem disruption, overuse of natural resources and massive pollution have done its job. “Nearly all of the changes that can potentially help mitigate our environmental crises will also mitigate our social crises and our misery. So exactly why are so many people so reluctant to change?” (Mattis 2018).

Many believe, based on a small number of studies, that we need to "keep information simple and hopeful in order to effect change" because the climate problem is just too "overwhelming, which incites hopelessness and inaction" for the general public (Mattis 2018). “In her book Environmental Melancholia, Lertzman argues that unprocessed grief about ecological devastation is a big part of what prevents people from addressing environmental challenges. This ‘arrested, inchoate form of mourning’ keeps people locked in a state of inaction, she writes” (Riederer 2019).

But, is this hopelessness and inaction really despairing, or is it denial in not wanting to admit that each one of us personally has a role to play in the problem and in the solution? And, that we each need to "change our way of life in innumerable ways, and none more so than the wealthy."

Critics claim doom and gloom messaging is disempowering and counterproductive, so is there a better way to communicate about the urgency of climate change? Jon Christensen, Adjunct Assistant Professor in Environment and Sustainability at UCLA thinks so and conducted a real-life experiment with Climate Lab as part of an online mini series of videos campaign to help educate and make a compelling connection to diverse audiences about the possibilities of climate change devastation and what needs to be done to get to carbon neutrality by midcentury. Based on feedback gathered from a previous report co-authored by 50 UC researchers, these creators knew they wanted to have “an approachable, even fun and humorous, trusted mentor that would appeal to diverse audiences.” In so doing, they collaborated with a creative communications team and a professional video crew. “Subjects of the video series ranged from why people are so bad at thinking about climate change to the impacts of our consumer habits.” Three stories that stood out had some important key findings:

They connected individual actions to collective actions, they showed people taking action and they modeled a positive spillover effect. People respond well to two things: stories about what they can do, and how they can be part of a broader effective change. And those two things need to be connected. So, by all means, let’s talk about how urgent action is, and imagine the worst results of not acting, but let’s be sure to tell stories that lower the barrier to taking action, too, individually and collectively. [Christensen 2017]

Mattis' method and technique of looking at things was decidedly different, citing a wide array of reports and news articles by scientists, economists, government panels, politicians, climate activists as well as consumer television shows, movies, historical political policies, polls, surveys and interviews were used along with citations from her own informal environmental education, works from other anthropological collected data and science communication scholar research using examples from the Club of Rome and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

In 1972, the Club of Rome, a consortium of scientists, economists, politicians, diplomats, and industrialists, produced a lengthy scientific report entitled Limits to Growth. Their work predicted a collapse of the human population due to our unchecked economic growth and resource depletion. While their estimates were condemned as alarmist and overreaching, independent researchers have updated the report for the 50th anniversary of the club’s inception, and have largely found that the conclusions from the original still hold. [Mattis 2018]

Even Saturday Night Live’s Weekend Update seemed to support the idea of hopelessness and inaction in the wake of the IPCC news (Mattis 2018) and "what's essentially an obituary for the Earth" (Ivie 2018):

Colin Jost: Scientists basically published an obituary for the earth this week and people were like, “Yeah, but like what does Taylor Swift think about it”….We don’t really worry about climate change because it is too overwhelming and we’re already in too deep.

Michael Che: That story has been stressing me out all week. I just keep asking myself “Why don’t I care about this?” I mean, don’t get me wrong, I 100% believe in climate change yet I am willing to do absolutely nothing about it.

Margaret Klein Salamon, the author of The Climate Psychologist blog and founder of a climate-advocacy organization, The Climate Mobilization relies on more informal techniques by “hosting periodic phone sessions where callers dial in to discuss their feelings about climate change and climate activism.”

All sorts of emotions have come up on these calls: guilt and shame, grief, panic, helplessness, even “destructive glee” from people who are angry that their warnings haven’t been heeded. Salamon stresses the importance of processing climate change as an emotional and personal phenomenon, not just a scientific one. [Riederer 2019]

A statistical approach was Arnold's method of determining the dominant narrative of national media coverage of climate, done through an analysis of stories containing the key terms “climate change” and “arctic” in diverse news outlets (including NPR, NBC News, ABC News, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The Washington Post) over a five-year period. A majority of news stories focused on the science of climate change and not people, except for “experts,” including scientists, policymakers and advocates. "Few included the voice of actual residents" (Arnold 2018).

Of the minority subset of stories that had a human subject at the center of the narrative, it was that of an indigenous person or community. Of that subset, the individual or community was overwhelmingly framed as a victim facing environmental threat or loss. The dominant Arctic climate change story involving people focuses on coastal erosion and the prospect of relocation, a story that has been told repeatedly for more than a decade with little discussion of mitigation or adaptive responses. [Arnold 2018]

John Fraser is a conservation psychologist who has studied burnout and trauma among people doing environmental work. “We have to move beyond terrorizing people with disaster stories,” he tells Riederer in an interview.

Psychologist and communications expert Renee Lertzman was a panelist at the annual conference of the Society of Environmental Journalists in October, 2017 that was titled “Doomsday Stories: The Ethics and Efficacy of Doomsday Reporting.” She argued that it is necessary to “blow up the dichotomy” between fear and hope, or truth and positivity. The problem with the horror-story narratives is not necessarily that they are frightening, she said, but that they are presented almost cinematically—placing people outside of the action in the “politically neutralizing” position of “titillated, excited, fearful spectators.” (Riederer 2019).

Climate psychologist Per Espen Stoknes confesses as to why people are reluctant to act to halt global warming, "We have several brain challenges when it comes to dealing with the abstract, slow moving, invisible threat of climate change. It doesn't really trigger our evolutionary risk lamps. Since it's invisible and often described very abstractly, people distance themselves from it" (Quaile 2019).

Furthermore, Stoknes claims that there are a lot of studies that show how people tend to disengage and the reason is fear and guilt feelings, which tend to be evoked by the "doom framing," and then we start to shut down. "These are feelings that make us passive not active. We know from psychotherapy that just shaming people or making them feel guilty does not enhance the willingness to change. People start to avoid those messages and people who make them feel bad" (Quaile 2019). Such reporting should also include responses and innovations, and increase pressure on policymakers to act, rather than offering excuses for inaction.

Data presented in both the textbook and by the authors cited here agree: on a large scale and only in the last few hundred years, "we have altered geology, chemistry and biology across the globe that has left a wasteland of ecosystem destruction, species decimation, acute and chronic toxic pollution" which has ultimately created a catastrophic global climate change.

For most of our 200,000 years, Homo sapiens, like the other species living among us, affected local areas in limited ways that were not completely detrimental and irreversible. We didn’t leave traces of persistent organic pollutants at the poles of the globe, having manufactured and used them thousands of miles away. We didn’t leave radioactive vessels at the bottom of the ocean and heaps of radioactive materials in piles that we hope will not be touched for tens and hundreds of thousands of years. We didn’t deforest and desertify swathes of land the size of states and countries. We didn’t drastically reduce the number of insects and pollinators of our food supply. We didn’t kill the majority of species of large mammals. We didn’t leave a supply of chemical and plastic waste in the oceans, the quantity of which will soon outnumber the productive biota of the sea. And we didn’t drastically alter the gaseous concentrations of the atmosphere, thereby transforming the entire planetary climate. Some humans never did. [Mattis 2018]

The American Psychological Association created a task force in 2008-2009 to look at the connection between psychology and climate change. While most agreed climate change was important, they didn't “feel a sense of urgency” (Riederer 2019).

The task force identified several mental barriers that contributed to this blasé stance. People were uncertain about climate change, mistrustful of the science, or denied that it was related to human activity. They tended to minimize the risks and believe that there was plenty of time to make changes before the real impacts were felt. Just ten years later, these attitudes about climate feel like ancient relics. But two key factors, which the task force identified as keeping people from taking action, have stood the test of time: one was habit, and the other was lack of control. “Ingrained behaviors are extremely resistant to permanent change,” the group stated. “People believe their actions would be too small to make a difference and choose to do nothing.” [Riederer 2019]

Fraser wants people not to feel alarmed, but activated, and he takes a relentlessly positive, solutions-oriented attitude. “We got trains all the way across America in a few years, and people on the moon in a few years,” he said. And ideas for climate moonshots abound: negative-carbon-emission plants are prohibitively expensive, but they do exist; some advocate for reviving nuclear power; proponents of a Green New Deal call for ending fossil-fuel extraction and subsidies, and radically expanding public transportation. In Silicon Valley, ideas are emerging that rely less on politics than on technology, like flooding some deserts to grow carbon-sucking algae beds, or using electrochemistry to get rocks to absorb carbon from the air. Fraser believes that the most productive way to communicate about environmental problems is to emphasize the positive solutions that exist. “What we need to promote is hope,” he said. “The first step to a healthy response is feeling that the problem is solvable” (Riederer 2019).

Responses to climate change are often discussed as a spectrum, with denial and disengagement at one end and intense alarm on the other. We are getting more alarmed. In 2009, a Yale and George Mason study grouped Americans’ responses to climate into six categories: alarmed, concerned, cautious, disengaged, doubtful, and dismissive. In 2009, eighteen per cent were alarmed; in 2018, that number had risen to twenty-nine per cent. [Riederer 2019]

During the process of "Climate Lab", an experiment in the art and science of climate communication, Jon Christensen pointed out three of the stories that were the most popular: "why we need to be nudged to think about climate and like to compete to be greener than others, how we can reduce consumer waste individually and collectively, and how simple solutions can lead to big reductions in wasted food."

It was his belief that "people respond well to two things: stories about what they can do, and how they can be part of a broader effective change. And those two things need to be connected." (Christensen 2017). His team plans to continue with "Climate Lab" as well as creating a real online class for undergraduates and other universities in hopes of continuing a "positive spillover".

"If you look at the science about what is happening on earth and aren’t pessimistic, you don’t understand data. But, if you meet the people who are working to restore this earth…and you aren’t optimistic, you haven’t got a pulse.” —Stephen Hawking

Marcus Vetter's film The Forum, which premiered in Amsterdam in November 2019 at the world's largest documentary film festival was the latest in a series of documentaries focusing on climate change and globalization, and might reach a new wave of people, and help them understand a few connections and not to take an overly pessimistic view of the future; putting your head in the sand is not an alternative; so portray people who set a good example (Kürten 2019).

Considering everything presented, the validity of the information cannot be ignored; we need to promote hope, tell the story that the problem is solvable by keeping the information simple and hopeful in order to effect change. We have to remember how important it is to take action and evaluate the negative repercussions of doing nothing. In order to save the world, "everything needs to change" and "we must all take the lead: eat, sleep and breathe with our environment in mind." And, we need to do this now” (Mattis 2018).

Decarbonizing the economy will be difficult, but it must be done. It will be hard—but not as hard as surviving the catalogue of disasters that will befall us if we don’t. The thing to grieve, then, is not the Earth’s habitable climate but, instead, the century of carefree car-driving and reckless deforestation, the years of eating meat with abandon and inexpensively flying around the world—and the massive economic growth that this system has enabled. Overhauling the fossil-fuel economy will represent a true loss, but its sacrifices will be nowhere near the alternative. [Riederer 2019]

The plea by Greta Thunberg rings true: we need to examine why we think it's okay to destroy the climate with the way we are living and how we can change that to preserve the planet for future generations.

"…We can’t save the world by playing by the rules because the rules have to change. Everything needs to change and it has to start today….To all the politicians that pretend to take the climate question seriously, to all of you who know but choose to look the other way every day because you seem more frightened of the changes that can prevent the catastrophic climate change than the catastrophic climate change itself… Please treat the crisis as the crisis it is and give us a future".

— Greta Thunberg, 15 year-old climate activist speaking at the Helsinki climate demonstration, October 20, 2018

The research shown throughout this paper has helped me understand that many ways of living that I take for granted are actually contributing to the overall climate crisis. I am hopeful that this paper sheds light on how we need to explore new ways of curtailing the destruction and continue to rethink existing technologies to stop destroying our precious climate. I think Koko the Gorilla summed it up well: “Earth Koko love.”

“Koko3” by FolsomNatural 2016 CC BY

Adams, Lucy. “Interview by the author Elizabeth Arnold in Kivalina , Alaska”. July 2008.

Arnold, Elizabeth. “Doom and Gloom: The Role of the Media in Public Disengagement on Climate Change, 2018”. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://shorensteincenter.org/media-disengagement-climate-change/#_ftnref14.

Behrensmeyer, Anna K. “Climate change and human evolution”. January 27, 2006.

Boycoff, Jules M. and Boycoff, Matthew T. “Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press,” Global Environmental Climate Change 14 (2004) 125-136.

California Earthquake Authority Accessed November 29, 2019. https://www.earthquakeauthority.com/Press-Room/In-the-News.

Christensen, Jon. "Climate gloom and doom? Bring it on.” The Conversation August 8th, 2017. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://theconversation.com/climate-gloom-and-doom-bring-it-on-but-we-need- stories-about-taking-action-too-79464.

Cox, Sally Russell. Interview by the author Elizabeth Arnold in Anchorage, Alaska, March 16th, 2018.

Fraser, John. Interview by the author Rachel Riederer, March 2019

Fridays for Future: What next?. June 21, 2019. Accessed November 29, 2019h ttps://p.dw.com/p/3KpG7.

Ivie, Devon. “Vulture”, October 14, 2018. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://www.vulture.com/2018/10/snl-tries-to-scare-you-into-caring-about-climate- change.html.

Koko the Gorilla. June 24, 2018. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eXS0rzf4iYo>

Kürten, Jochen. “Climate change, globalization, the economy — can movies save the world?”. November 22, 2019. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://p.dw.com/p/3TWTw.

Lertzman, Renee “Doomsday Stories: The Ethics and Efficacy of Doomsday Reporting”. Society of Environmental Journalists annual conference, October 2017

Marx, Bill “‘Bad Environmentalism’ — Laughing at Gloom and Doom”. March 17, 2019. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://artsfuse.org/181816/book-interview-bad-environmentalism- laughing-at-gloom-and-doom/.

Mattis, Kristine. “Eco Crises: Doom & Gloom, Truth & Consequences”. October 30th, 2018. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://www.counterpunch.org/2018/10/26/eco-crises-doom-gloom-truth-consequences/.

Moser, Susan. “Communicating climate change: History, challenges, process and future directions”. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 1 (January- February):31-53 2010.

Quaile, Irene. “Psychology behind climate inaction: How to beat the 'doom barrier'” May 24 2019 Accessed November 29, 2019. https://p.dw.com/p/3ISxS.

Riederer, Rachel. “The Other Kind of Climate Denialism” March 6, 2019. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/science/elements/the-other-kind-of-climate-denialism

Salamon, Margaret Klein. Accessed November 28, 2019. http://theclimatepsychologist.com/author/theclimatepsychologist/

Saturday Night Live. Weekend Update: U.N.'s Climate Change Report - SNL October 13, 2018. Accessed November 28, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=07oe1m67eik.

Schoenberg, Arnie. “Homo sapiens futures; Doom, Gloom, and hope?” in Introduction to Physical Anthropology. Last modified November 17, 2019. http://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/bio/intro/section8.html

Steiner, Felix. “The eco-warriors of climate protection”. DW Akademie. September 20, 2019. Accessed November 28, 2019. https://p.dw.com/p/3Pxxi.

Stoknes, Per Espen. Interview by the author Irene Quaile. May 24, 2019.

Wallace-Wells, David. 2019. The Uninhabitable Earth.