San Diego City College Student Anthropology Journal

Edited by Fernanda Corral

Published by Arnie Schoenberg

http://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/journal/spring2019

Volume 3, Issue 1

Spring, 2019

latest update: 6/25/22

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

More issues at http://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/journal/

As science reveals human evolution, we are offered increased opportunities to understand our potential. We can utilize this new-found knowledge to transcend our current boundaries. Although we invest a large portion of our effort to develop tools, technology, and institutions, there are many valuable pieces of information that will further our understanding of what made us, humans, what we are, what elements led us to where we are today, and where we are headed. This literature review seeks to explore the origin and evolution of the human mind beginning with early humans and concluding with the future of our species. Analyzing various experiments and studies related to early humans, brain development and cognitive ability, we will explain how humans have come this far as a species and what direction we are going in. History will repeat itself unless we learn from it and progress within our experience.

The earliest evidence of hominins appears in Chad, Africa approximately 7 million years ago with the archeological find of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, a primate skull. However, this skull did not provide enough evidence to definitively postulate it was a bipedal ancestor of humans (Smithsonian Institution, 2018). Up to this point, we had various skeletons and fossils of our supposed ancestors, including the famous Australopithecus fossil, Lucy, but nothing established a definitive correlation with our ancestors. It was not until the discovery of the Laetoli Footprints did we have any palpable evidence of our human ancestors. These footprints that solidify our bipedal ancestors were found in 1978 by two scientists in Tanzania (Raichlen, 2010). They have estimated that these footprints are approximately 3.6 million years old, creating a 3 million year gap with little to no evidence of human life. The footprints validated the popular claim that the genus Australopithecus is, in fact, a stopping point within human taxonomy.

Establishing our general existence as a species is only a benchmark for our true evolutionary focus—human cognitive ability. The dawn of intelligence seems to be rooted in a critical transformation in our ancestors called encephalization. Approximately two million years ago, the genus Homo habilis rose to a certain level that re-classified itself within human taxonomy, triggering an enormously complicated sequence of steps that lead to our modern-day human brain. Following Homo habilis was Homo erectus. The two are primarily distinguishable because of the massive difference in brain size. Homo habilis had a brain size of approximately 600cc compared to its successor, Homo erectus, with a brain size of 800cc. The millions of years that it took for development eventually led to the modern human with a brain size of approximately 1300cc (Lumsden, 1983).

Approximately two and a half million years ago the first known tools were created (AHC, 2012). The appearance of stone tools established the first signs that Homo habilis had the ability to think beyond the means to survive. The significance of the appearance of tools is profound because it means that our ancestors began to truly use their cognitive abilities, they began to understand that using a sharp rock would have made their tasks easier. As archeologists uncovered more tools, they began to recognize a pattern in how these tools were made, a method referred to as flaking. Flaking is a method used to chip away fragments of rock to create a sharpened edge. This is important because not only did our ancestors realize they could use sharp objects to their benefit, they began to make sharp objects themselves. To take this a bit further we want to highlight an experiment that was conducted in 2018 by a group of scientists in London. The hypothesis for this experiment was rooted in the communicative abilities of these early Hominins, and how they shared the knowledge of stone tool creation. Their findings postulated that some form of gestural language was required to pass on the knowledge of flaking (Cataldo, 2018). To the current date, there is absolutely no evidence supporting the use of language in any form. Although there is no evidence beyond their claim, it seems logical that these early humans must have had some form of communication.

After the discovery of stone tools, the next big step in our cognitive development was discovering the first known burials. Approximately 300,000 years ago in Spain, Neanderthals began burying their dead. This discovery was so significant because of what it meant for the cognitive ability of Neanderthals. Having a system in place to bury the dead subsequently means that there must be some form of religious belief. Scientists believe that a concept so complex as religion would require the use of spoken language (AHC, 2012). There is no way to conceivably know the mode of communication or language that was used with these Neanderthals, but it is evident that these people had a way to communicate amongst themselves.

At this evolutionary stage, we could walk on two feet, which permitted the use of our hands. From there we understood that we could make and use tools. Then we thought of the afterlife and we began burying our dead. However, going from one event to the next took millions of years, and year after year something brilliant was taking its course to make all of this possible—natural selection. Natural selection is defined as, “a natural process that results in the survival and reproductive success of individuals or groups best adjusted to their environment and that leads to the perpetuation of genetic qualities best suited to that particular environment” (Merriam-Webster, 2019). Essentially, this means that our ancestors were considered the fittest species to continue to reproduce within that environment. Nature recognized that our ancestor’s genetic makeup best matched the environment and because of this, we have evolved and developed exponentially compared to our primate relatives.

Following the evidence of our ancestral existence, bipedal primates began appearing everywhere. Homo sapiensand Neanderthals started to emerge all over Africa, Australia, Europe, and Asia (EMHS, 2013). Along with these appearances came new evidence of enhanced cognitive abilities. About 35,000 years ago, people that we refer to as Aurignacians lived in deep caves in Western Europe where they painted and engraved numerous animals and geometric forms. They occasionally did so with great mastery and with an obvious appeal to the aesthetic senses. The Chauvet Cave located in southern France is a great example of how artistic and resourceful our ancestors had become. Within this 30,000-year-old cave, there are over 100 different images created with various techniques that populate these walls (La Grotte Chauvet-Pont D'Arc, 2015). Our ancestors were no longer primarily focused on surviving, they were leaving a story behind for others to see, admire, and learn from.

Survival went from a point of urgency to a matter of strategy, and along with this, we became expressive creatures by means of art, jewelry, and advancements in the tool industry (i.e. Sexy Hand Axe). Becoming aware of the immense benefit of working together and creating more intrinsic groups allowed them to collectively think. Collaboration was an advantage in their environment and it created the means not only to endure, but to thrive. As a collective, humans began to understand that it was not necessary to travel with a hunter and gatherer mentality to survive, but it was possible to stop in a strategically ideal location to take on a more sedentary lifestyle. Once this shift occurred, human development skyrocketed.

Evidence supports that approximately 23,000 years ago near the Sea of Galilee in Israel, the first agricultural site indicated that a group of humans lived and farmed for grain (Snir, 2015). This type of lifestyle is extremely unprecedented in regard to human behavior. Typically, our ancestors traveled with the seasons and followed the warmth of the sun, growth of plants, and the presence of wild animals, as food. As tools advanced, an understanding of the environment grew, humans no longer needed to travel to survive. Instead, they began to create long-term camps that provided shelter for them and their belongings. Previously, moving with the seasons required these people to travel light and never allowed for more resources than what was necessary. A more consistent living arrangement allowed these people to do something that had never been done before—gain a surplus of resources. Having a designated location to store tools, weapons, food, and clothing gave rise to a new way of life.

Having a surplus not only allowed people to live in settled locations, but it also gave our ancestors a new reason to develop and advance beyond what had already been created. They now generated specific jobs to manage the different aspects of their camps. Jobs such as tool/ weapon making, clothing making, farming, cooking, and security became necessary elements to maintain their new lifestyle. With these jobs being divided among individuals and not being the responsibility of the entire group as a whole, they were able to focus on their craft and continue to make developments that made their jobs easier. For example, the farmer did not need to necessarily worry about how to make clothing or what was needed to secure their resources. Farmers could spend their time discovering new ways to grow wheat and grains, or how to better care for the cattle. They could focus on their specific trade without spending too much time worrying about every aspect of their survival. Our ancestors were able to start developing and improving exponentially in multiple areas.

This revelation ended the Paleolithic era and entered into the Neolithic Revolution. This new era brought domestication of plants and animals, new resources (clay, metal, iron), improved housing, specialization of jobs, and more settlements than ever before. The most important aspect of this era was the appearance of written communication. The significance of this allowed the transmission of ideas and concepts beyond one’s own settlement. Now, not only are humans developing within their own societies the are sharing that information with other people allowing them to develop and build upon their work. For the next few thousand years, societies rose and fell building upon what was left before them. Ancient societies like the Egyptians, Medieval Kingdoms, the Greco-Romans, Chinese Dynasties, The Roman Empire, the Renaissance, all lead to the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution created the building blocks for what our species is able to do today. These societies learned from one another, understood their mistakes, and improved from what was left behind. Every generation of humans has left behind a little more knowledge than what they started with, which allows for future generations to go beyond what was possible for them.

Understanding our history is necessary in order to better understand our capabilities. Seven million years ago, evidence demonstrates that we once lived in trees. Years ago, we descended and began walking on two feet. Our brain began to grow in size allowing us to become articulate thinking beings. We became curious and strategic, which in turn began an era of advancement and creation. This pattern of advancement provides insight and permits reasonable hypotheses on what we can expect in our future. Technology is essentially the modern stone tool of our generation. In modern society, we use technology every day to make our lives easier. Because of technology, we have been able to change the world and create a globalized network of communication to continue the advancement of our species. Due to the impact of communication, the development of stone tools is analogous to how we communicate in present-day in order to share ideas and learn from one another. Before the age of technology, and after language was developed, communication with other people was difficult and sharing important relevant knowledge took a lot of time and effort. With the advancement of technology, we can share knowledge within seconds to various people on the other side of the world simultaneously. To further this point, we have the ability to share knowledge with people who speak different languages with the use of translating applications and websites. Communication was vital for ancestors to progress and it is just as important for our advancement today. We would argue that communication and the continued advancement of technology may be the most important aspects of our continued survival.

As the unknown continues to drive us towards discovery, whether it be for spiritual understanding, technological advancements, or our inherent hedonism, we have transformed discovery into control. Our ability to improve our species has done something amazing, we have removed natural selection as a factor from our species. It was natural selection that allowed humans to develop the brain and descend from the trees to walk on two feet. Natural selection allowed us to begin to think for ourselves. Now in the age of technology, natural selection has nothing to do with what will happen to humans. We create the change that we want to see. For example, the work done with DNA technology is groundbreaking and life-altering. Scientists have recently begun studying the ability of cloning genes that has a myriad of real-world implications. Such as “pest-resistant plants, vaccines, heart attack treatments and even entirely new organisms” (F. Sarah, 2019). This concept of manipulating DNA to defy the “natural order” of things is almost unfathomable. In early 2018, scientists in Shanghai defied the odds and cloned the first two primates in history (Cell Press, 2018). This milestone is extremely important because as primates ourselves, our DNA is closely related to that of monkeys. In fact, DNA research shows us that humans have many of the same genes as other life forms as well, including plants, bacteria, and other animals (Minerd, 2000). This research has relatively only just begun, and we have already made huge strides towards humanmade evolution. Speculation of the work that has already been done has led us to believe that one day scientists will be able to dictate and code every aspect of our DNA. We will literally be creating life without the need for sexual reproduction.

Another example of the strides our species has made in technology is the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI). This branch of computer science is dedicated to creating machines that have the ability to “think” like humans. Seven million years ago, humans did not exist. Now, in modern society, we are creating inanimate objects to think like we do. In 2016, a robot named Sophia was created. She is a human-like robot that thinks and talks for herself. She is the culmination of years and years of trial and error. And in 2017, she became recognized as a citizen of Saudi Arabia, becoming the first non-human citizen in any country around the world. We have come a long way from descending the trees, to building robots that can hold intuitive conversations. This technology will impact our society and future societies in a unique unparalleled fashion. This has implications in areas such as the job force, robot/human rights, and technological advancements. Our future is something that rivals concepts from a fiction book.

The human capacity to think, understand, question and explore is truly something incredible. We are living in unprecedented times where the sky is not the limit. For our ancestors, the sky began as a means of guidance and light. To the modern human, it is a place unknown that we have and will continue to explore. Mystery has been a catalyst on our quest to explore the unknown. We have a visceral drive to decipher the obscure and unfamiliar. It began when our ancestors discovered the use of tools. Their minds began to grow and question the things around them. Our minds evolved as time passed and we became inquisitive about every aspect of our lives. We have reached a moment in time where there are no boundaries by nature. The only obstacles we face are created by ethical standards we have established. The future is unknown, but we now have the foresight and understanding to create a future that we want to live in. Natural selection once decided who or what was fit enough to survive in this world—now, we decide what constitutes as fit to survive.

Cabrera, Sergio and McBride, Trent “Dust” 2019. https://youtu.be/Tu4VA1-zMlw

“Archaic Human Culture.” (AHC), Evolution of Modern Humans: Archaic Human Culture, 2012, Dennis Oneil , www2.palomar.edu/anthro/homo2/mod_homo_3.htm. Link from chapter 6.1.3

Cataldo, Dana Michelle, et al. “Speech, Stone Tool-Making and the Evolution of Language.” PLoS ONE, vol. 13, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 1–10. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191071.

Cell Press. "Meet Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, the first monkey clones produced by method that made Dolly." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 24 January 2018. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/01/180124123231.htm>.

“Early Modern Homo sapiens 201.” (EMHS), Evolution of Modern Humans: Early Modern Homo sapiens.Dennis Oneil, 2013, www2.palomar.edu/anthro/homo2/mod_homo_4.htm.

F., Sarah. “Practical Applications of DNA Technology.” Study.com, Study.com, 2019, study.com/academy/lesson/practical-applications-of-dna-technology.html.

Lumsden, Charles J. and Wilson, Edward O. “The Dawn of Intelligence: Reflections of the Origin of Mind” The Sciences, March/April 1983.

Minerd, Jeff. “Trend Analysis: Genetic Engineering Increases Human Power.” Futurist 34, no. 2 (March 2000): 23. http://search.ebscohost.com.libraryaccess.sdcity.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=2796140&site=ehost-live.

Raichlen, David A, et al. “Laetoli Footprints Preserve Earliest Direct Evidence of Human-like Bipedal Biomechanics.” PloS One, Public Library of Science, 22 Mar. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2842428/#!po=1.35135.

Schoenberg, Arnie. 2009. Introduction to Physical Anthropology.

Snir, Ainit, et al. “The Origin of Cultivation and Proto-Weeds, Long Before Neolithic Farming.” PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 7, July 2015, pp. 1–12. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131422.

Staff. 2019 “Natural Selection.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/natural%20selection.

Staff. “The Aurignacians.” La Grotte Chauvet-Pont D'Arc, 2015, archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet/en/aurignacians .

Staff. “Walking Upright.” The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program, 17 Oct. 2018, humanorigins.si.edu/human-characteristics/walking-upright.

The emergence of art is a significant and crucial point in human evolution. Art separates humans from all other animals, as it is proof of higher cognitive function and abstract thought. The evolution of art coincides with the increasingly more advanced thinking of early human ancestors (Blum, 2011:196). From these examples, the culture in which these artistic creations were made can be better understood, which allows for interpretation of the early art and the weight it carries. Art is a determining factor in the distinction between humans and other primates.

In order to explore art, it should have a clear and solid definition. The modern interpretation of art covers everything that art has evolved into in the contemporary world, including music, dance, painting, drawing, bodily adornments, and more (Dissanayake, 2002:50). This broad array of mediums makes it difficult to decipher art from years past because we do not have any cultural information to which the art can connect. Did early humans intend to create something with meaning beyond practicality or pure instinct when they danced? To look at art from a scientific viewpoint in the evolution of the brain of a species, the art under question should be clearly seen as art by the ones who created it, otherwise, it would be too subjective to provide any substantial findings.

Does art have to have form? Can a few chicken scratches on a seashell be considered art? For the purpose of clarity, when examining art without context, I define art as anything purposely and methodically made outside practical purposes. Works such as hand paintings in caves are easy to see as art. Paint and pigments are applied to decorate a surface. No matter if the intention is spiritual, ritual, or purely aesthetic, it is art. Lines carved into a seashell are more difficult to determine because the intentions of the “artist” are unclear. What if the early human ancestors, referred to as hominins (Schoenberg, 2019:6), who made those carvings were only doing so to test out a sharp stone they were working with? The intentions and cultural background are not apparent. Nevertheless, I will include anything that could be considered the beginnings of art, as art did not start with someone going off into a cave and creating a masterpiece. It began as a slow process of humans being inspired to gradually step away from practical creations, such as tools, and verge into more aesthetic and symbolic things (Dissanayake, 2002:129). To narrow down the broad range which art encompasses today, I will not be discussing music, language, or dancing; rather I will interpret the deliberate mark makings such as paintings, carvings, and sculpture, as I believe these evolved differently than other forms of art such as dancing and language. Additionally, these art forms have been preserved from hundreds of thousands of years ago, whereas purely cultural art forms, such as dance, have not.

Art originally developed from tools that were becoming increasingly ornamental or aesthetic, with the first ones being made with green lava and smooth pink pebbles approximately 2.5 million years ago. Around this time, there is evidence of early human ancestors carrying around things other than tools for no practical purpose. While the hominins did not do anything to these objects for them to be considered a work of art, they are pretty things, which shows an interest in the aesthetic (Dissanayake, 2002:70). Hominins during this time period were known asHomo habilis; the first hominin close enough to Homo sapiens to be considered to be within the genus Homo (Schoenberg, 2019:6.5.1). Other examples of specialized tools are spearheads specifically crafted so the stone had an imbedded fossil in the center of the flat side of the spear, created 250,000 years ago (Dissanayake, 2002:71). These samples could be considered the earliest forms of art, as they mark the beginning of thought beyond simple survival or functionality.

The first art apart from decorated tools were carvings. One discovery of carvings made into seashells suggests that these carvings could be as old as 500,000 years old. Researcher Eugène Dubois found a mollusk shell with several deep, angular scratches that created a geometric, almost zigzag pattern across the outside of the shell (Kemp, 2017). While these scratches are distinct and deliberate, the intentions of the maker are not clear. It does not seem to be of any symbolic significance. However, it is so substantial because it was made by Homo erectus, a primitive species whom scientists did not think were capable of creating such marks (Kemp, 2017). Additionally, approximately 100,000 years ago there were more clearly defined marks on bones, varying in shapes and contour. This is the beginning of symbolic expression (Dissanayake, 2002:72).

From scratches on shells and bones, we move onto more clearly representational and artistic expressions of early hominins. The oldest rock art was found in Africa and was created 75,000 years ago (Blum, 2011:196). Around 70,000 years ago, stylistic differentiations of artifacts were emerging between different hominin groups around the world (Dissanayake, 2002:72). Blum hypothesizes that this major jump in artistic representation could be due to a genetic variant associated with changing brain function that appeared which allowed for better survival advantages, which made the hominins more intelligent, leading to a surge in art (Blum, 2011:196).

Dissanayake theorizes that due to the need for survival, hunter-gatherers needed to be interdependent. Finding food when food is not readily available would require more complex thinking, as they would learn to think ahead to what they need in the future. This kind of intelligence allows for the ability to learn, remember, and understand (Dissanayake, 2002:126). Hominins, as they evolved, grew to have larger brains, which allowed them to have more advanced thought processes, called encephalization (Schoenberg, 2019:6.1.2). As the hominins got better at finding and maintaining a food supply, they would inevitably have more leisure time. That, combined with the now evolutionary increase in intelligence, would cultivate an environment in which curiosity and creativity were sparking, leading to amplified artistic behavior and thinking (Dissanayake, 2002:127).

Lastly, we move onto the more advanced forms of art: cave paintings and sculptures. Hand stencils are considered the first style of painting. It is a technique in which the artist places their hand firmly against a rock face and blows pigment onto the hand, creating a negative painting of the hand. The earliest dated hand paintings are from 39,900 years ago and were created in caves in Indonesia. These incredibly old paintings survived the transitional years between the Middle and Upper Paleolithic periods and mark the true beginnings of art as we know it today. In the same cave, next to the oldest hand stencil in the world, is a depiction of a pig painted 35,400 years ago (Ghosh, 2014). Figurative paintings of real animals and people mark a huge jump in artistic ability, and therefore solidifies the intelligence of the hominins who formed them.

While there is little known about the cultural interactions of the hominins who created these works of art, information can be inferred from the location, tools, and depictions shown through these works of art, especially in the cave paintings. The early artists would travel through complex and dangerous caves to reach a transcendent space to begin their work. Evidence found in these caves suggests that they would have their assistants carry decorated torches and stone lamps fueled by animal fat and moss or pine needles (Blum, 2011:197). They would also bring a pestle to grind the pigments and paints made up of iron oxides in the colors of red and yellow, Manganese dioxide and charcoal made of burned wood were used for black outlines, and kaolin and mica for white. Brushes made of animal hairs were used along with the artists’ fingers to paint (Blum, 2011:198). Although primitive compared to the many works that can be seen today, the high-quality art was not seen as a lowly pastime, rather, it was a trained skill. The previously discussed stylistic differences in hominin groups attest to this. Many paintings show not only the use of paints to portray animals and other forms, but also the contours and formations of the cave itself to create the images. The artist would plan the pre existing cracks, bumps, and fissures to fit into and add to the final painting (Blum, 2011:198).

The difficult and perilous placement of the paintings suggests that they were to be revered and sacred places. Many anthropologists believe that the artists saw their paintings as spiritual, both figuratively and/or literally. Whether the cave walls were a physical separation from the spiritual world, or that the depiction of literal forms somewhat captured their physical counterparts, the paintings may have been an attempt to communicate with the spiritual elements. Theories as to the nature of the communication are widely varied. Some claim that the shamans or artists were attempting to entice, appease, or atone for killing the animals depicted. Some also suggest that the artists may have believed that they could magically acquire the abilities of the depicted animals, as many of them were predators. One interesting aspect of this is that it strongly suggests a sense of empathy with the animals, which carried into their interactions with other humans (Blum, 2011:199).

Creating a literal representation of something in the real world carried a hefty weight in the culture of the early Homo sapiens. This may have been the reason for the incredible lack of violence in all depictions. The most graphic the paintings would become was two animals locking horns. There was never death or even bloodshed in the early depictions of animals, leading Blum to hypothesize that the portrayal of violence was prohibited (2011:199). Interestingly, the depiction of humans was also taboo. It is suggested that the culture believed that the forms represented through the art could capture the subject matter, possibly endangering them through magical control, possession, or destruction (Blum, 2011:200).

Blum psychoanalyzes the paintings to better understand the culture of the artists. He states that, contrary to popular belief, the artists of these monumental paintings were not just men. Evidence of women creating art in these caves is evident through the hand and finger marks formed (Blum, 2011:201). Women’s hands and fingers can be determined as female through a calculations of ratios of relative fingers including index and pinkie fingers (Messer, 2017). Art created by women and men may even have different meanings due to the differing perspectives in the roles that they played. Women may have painted female genitalia and other birth-oriented forms to magically insure pregnancy and reproduction (Blum, 2011:200). Sculptures were one of the only mediums in which a human figure was depicted. Many of these are believed to represent a fertility goddess, pertaining to the power of creation that females hold (Blum, 2011:202).

The ability to produce art is a uniquely human trait. Although studies have been done on chimpanzees to see if they too can create art (Dissanayake, 2002:67), it could be argued that it is not due to their abilities, but rather the interactions between chimpanzees and humans that allowed them to recreate art. Nevertheless, human ancestors were the first to show the ability to create art. This, as well as other reasons, is how humans have differentiated themselves from other primates in evolutionary history.

Anthropologists determine where the term “primate” stops, and “hominin” begins. Once again, a hominin is a bipedal human ancestor that does not include apes. Three important factors for separating humans from apes and chimpanzees are bipedalism, encephalization, and associated culture and tools (Schoenberg 2019:6.1). Bipedalism is the ability to walk on two feet. This transition allowed hominins to freely used their hands for tools, and eventually included art making (Schoenberg, 2019:6.1.1). While other primates, such as chimpanzees, use sticks and stones, hominins are unique in that they create innovative tools which they improve upon over time (Dissanayake, 2002:67). Encephalization is the study of the head, or more specifically, the brain. Overall, as hominins evolved, their brains got bigger, as did the portion of the brain dedicated to higher, more advanced thinking (Schoenberg, 2019:6.1.2). This also led to the ability to express abstract thoughts through art. Finally, the last determining factor is associated culture and tools (Schoenberg, 2019:6.1.3). As discussed previously, the innovation that came with tool making opened a new path for creativity, branching off into multiple forms of art, including carving, painting, and sculpture.

Art allows anthropologists to understand and decipher the culture in which it was created. Inferring information from the art itself and the location puts it into a cultural context which we would not have otherwise. Demonstrating the ability to clearly distinguish early members of the genus Homo from all other animals, art has proved to be an invaluable asset to anthropologists. The complex and abstract thought that goes into artmaking is a testament to the abilities of our early ancestors. Arts personal, raw, even sacred nature has preserved the thoughts of people living tens of thousands of years ago, left for us to decode and understand.

Blum, Harold P. 2011. “The Psychological Birth of Art: A Psychoanalytic Approach to Prehistoric Cave Art.” International Forum of Psychoanalysis 20 (4):196204.doi:10.1080/0803706X.2011.597429

Dissanayake, Ellen. What Is Art For? Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

Ghosh, Pallab. "Cave Paintings Change Ideas about the Origin of Art." BBC News. October 08, 2014 Accessed March 14, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-29415716.

Kemp, Christopher. 2017. “The First Art: The Earliest Hominin Engraving.” Natural History(10):34

Messer, A'ndrea Elyse. "Women Leave Their Handprints on the Cave Wall." Penn State University. July 28, 2017. Accessed May 18, 2019. https://news.psu.edu/story/291423/2013/10/15/research/women-leave-their-handprints-cave-wall

Schoenberg, Arnie. 2019. Introduction to Physical Anthropology. Version 3/21/19. Retrieved from http://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/bio/intro/index.html Accessed 19 April 2019.

My name is Kelli, this is my second semester of college. All throughout high school I was pursuing Science, and almost went into Chemistry because I love figuring out the world around me. However, I decided that I would be much happier following an artistic path. I am currently working towards getting a BA in Graphic Design and/or Illustration. I hope to one day to put those degrees to good use and become a concept artist.

Many of the issues we face today are a result of us taxing the environment. We often have a tendency to use things that the earth only has a certain quantity of. Sometimes we do something and not realize the consequences of our actions until later. Some examples might include the mass growing of corn or the widespread development of wind energy. Looking at past trends we are able to analyze how the environmental factors transformed the decisions we made. The path that we took through evolution helps to portray and illustrate why we evolved in the ways that we did. It is impossible to know the whole scope of events that may or may not have taken place, but through examining fossil records as well as oxygen isotopes, we can get a better understanding. The articles discussed here walk through how our evolution began, from the change in our diets, to the reason why some of our species may have died out years ago. Through doing this, we are able to use anthropological imagination to examine the ways that our evolution may have been affected by the fluctuating environment.

The movement we are most interested in is the movement that occurred approximately 200,000 years ago. At this time, Homo sapiens had begun to migrate out of Africa towards the area of Eurasia. The interesting thing about this is the driving forces that may have led them to migrate. A theory of migration and evolution proposed by Dr. Rick Potts from the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program is known as variability selection. He forms this hypothesis based on the idea that human evolution isn’t solely based on adaptation to their specific environment or trend. Humans migrated due to a lack of environmental stability, and they evolved to grow and thrive in a multitude of different environments (Potts, 2018:6).

Through the use of fossil records, as well as oxygen isotope records, it is believed that hominins evolved in a time that overlaps a significant period of environmental change on earth. Hominins are known as “all species of modern humans and early humans after their split from chimps about 14 million years ago” (Caperton, 2016). This species went through environmental changes that were more than just seasons. It was a time when ocean temperatures were increasing as well as glacial ice melting. These changing environmental patterns subsequently changed the environment in an irreversible way, requiring early hominins to adapt with it. The changes they would need to make to adapt include the development of tools needed to build, hunt, and scavenge for food as well as where they would be able to find their main source of food.

Tool making continues to play a large role in how we view early climate change and environmental effects of evolution. The turning point is once hominins became dependent on their tools for everyday use. Dr. Potts also talks about what is known as Oldowan toolmaking. According to the article written by Dr. Potts, early hominins carried tools over large spans and used them as a way to maneuver through changing environments—migration—which in turn meant changes in diet as they found new food sources from new areas. These tools, along with increasing sizes of the brain, provides a strong correlation between movement of these hominins and the varying tools used as evidence of environmental stressors and adaptation to new environments.

The use of, and dependence on tools as well as frequent movement found from fossil records, show a possible trading of tools, but also the coming of complex human emotions and further development into Homo sapiens. Dr. Potts describes situations in which groups could have possibly traded tools or other objects in an attempt to make allies or friends for food. When the environment put stressors onto one group’s food supply, he states that they may have used these relationships formed by tool trading to gain access to food. This is another example of environmental impact on encephalization and the patterns of social development can be seen as a starting point of further social complexity.

Moving from the Paleolithic era into the Neolithic, we see substantial growth in human cultural complexity, and population growth as well as increased brain size. It is a widely accepted idea in the science and historical communities that the time period between the old stone age and the new stone age was when agriculture and animal domestication began. Once humans spread out over continents, they stayed in groups making it difficult for some groups to provide enough food for everyone. Due to the difficulties some faced, plant and animal domestication, horticulture, and agriculture became the means for providing food for the whole group.

Merry Wiesner-Hanks et al., in the book A History of World Societies, writes about that time when the agricultural revolution took place and how it altered the landscape that we adapted to. The significance behind this transition from hunting and gathering to “farming” is a result of the tactics that were used in order to further their development. As planting habits continued, they eventually ended up stripping the soil of nutrients that sustained plants. Therefore, they had to move it elsewhere. Wiesner-Hanks states, “especially in deeply wooded areas, people cleared small plots by chopping and burning the natural vegetation, and planted crops in successive years until the soil eroded or lost its fertility, a method termed ‘slash and burn.’ They moved to another area and began the process again, perhaps returning to the first plot many years later, after the soil had rejuvenated itself” (Wiesner, 2018:18). This book goes over the development that early humans went through in altering their environment and subsequently how they altered their tools, habits, and their means of life.

The next point to be made is that of the entire Holocene time period. In a report written by Patrick V. Kirch, he lists outcomes of the destructive patterns and habits of early humans and the outcomes on their physical environment rooted in that period. Not only was the Holocene period a time of first farming and growing techniques, but it was also a time when early Homo sapiens experienced fire. He notes the seemingly close correlation with environmental changes and of specific times and the flora and fauna that also went extinct around that same time. The use of fire is said to begin before plants and animals were domesticated, according to the article. But fires that got out of control and burned large areas of land completely altered the landscape. Kirch uses the example of the outcome in Australia where a large increase of charcoal particles in sedimentary basins and lakes coincides with a large decrease in conifers, along with other rainforest trees. Other such examples of extinction due to serious environment alteration are the wingless birds from New Zealand known as dinornithids, along with many other extinctions experienced around that time frame. These are just a few examples of species that have been extinct because of human alteration of the land.

After the domestication of both plants and animals and the development of farming, the population of early humans started to increase. Along with the increase in numbers, we also started to see an increase in brain size and in complex thought processes. Another topic discussed in the article written by Patrick Kirch was that of migration patterns of early human’s growth habits. As our groups began to grow into villages and communities, human construction began to cover large areas of land and go in-between communities. Kirch talks about the continuing damage of the physical environment to meet their new needs and the impact on the flora and fauna around them.

Anyone who has followed-even in a cursory manner-the advances that archeology has made over the past half century in tracing the myriad of ways in which human population have irreversibly shaped the physical and biotic world we inhabit will recognize that global change has been underway since the early Holocene. The record if cumulative resource depression, translocation, extinctions, deforestation, erosion and sedimentation, expansion of agrarian landscapes, and increasing urbanization dispel any lingering views that pristine ecosystems persisted until the expansion of the industrialized West. [Kirch, 2005:6]

It is the extreme changes in our environment around us that altered our evolution alongside of our ever-changing environment.

An interesting theory brought up by Dr. Potts was that of animal distinction and replacement in East Africa as early hominins began migrating up and out of the continent. He cited many instances where animals that were too delicate or in need of specialized habitats and diets were replaced with smaller, and more “hardy versions” (Potts, 2018:16). The most notable being that of the Zebra, Equus oldowayensis, from between 780,000 and 600,000 years ago, and its replacement by Equus grevyi, a more common version you’d see today (Potts, 2018:16). It would be possible to link the reason for other hominins around the world, such as the Neanderthals, becoming extinct is because of the specialization they needed; they were ultimately replaced by us as the hardier “version”. Thus, as our environment continues to change, we have to alter ourselves to properly survive within our environment and we do so through adaptation and evolving; as these animals have done in the past.

A current growing concern is that of our population density and the damage it is causing to the plants and animals in our direct environments. Now that we are fully functioning humans with means to create, prevent, and solve almost any issue we face, our population has grown by exponential numbers. Jeffery McKee describes the growing impact that humans have on the biodiversity in the area specifically surrounding highly populated cities in the article “Outlook is grim for mammals and birds as human population grows”.

If we get to 11 million people, which is where we’re supposed to peak, then the amount of space you have per person is a lot smaller than that stadium. When you’re left with less space, there’s virtually no space left for most other species. Loss of species, and especially so-called keystones species that are important to the environment because they function as significant predators and prey, can disrupt ecosystems. Plants and animals also help the planet adjust to climate change, provide oxygen and are sources of food and medicine. [McKee, 2013:3]

A report published on May 6th, 2019 by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Service (IPBES) is the first of its kind to evaluate the current standings on biodiversity on this grand of a scale. The report culminates 145 expert authors from 50 countries, 310 contributing authors, and 15,000 scientific and government sources to evaluate our current global crisis and loss in animal population and biodiversity as well as its current trajectory. The current goals that are set for 2030 will not be reached by our current efforts to help climate change, and there is a current risk for losing many qualities given by the earth, such as food security and quality of life. Co-chair professor Josef Settele (Germany) states, “This loss is a direct result of human activity and constitutes a direct threat to human well-being in all regions of the world” (IPBES, 2019). The report states “the assessment’s authors have ranked, for the first time at this scale and based on a thorough analysis of the available evidence, the five direct drivers of change in nature with the largest relative global impacts so far. These culprits are, in descending order: (1) changes in land and sea use; (2) direct exploitation of organisms; (3) climate change; (4) pollution and (5) invasive alien species” (IPBES, 2019). It would seem like common sense to think that of course as us humans grow and expand cities; delicate species will sooner or later be pushed out. However, for those that cannot adapt to other habitats or that struggle not having a specific food source from their original habitat, we threw off the balance in our ecosystems. This could possibly be opening the door to other situations where animals that are hardier come in to take their place, as previously mentioned. The cycle continues, and displacement of species takes place. It is hard to say what the outcomes of such an instance would be over many years of replacement. However, it is possible to link it to our evolution moving forward from today. If it was possible in our migration patterns thousands of years ago, it could have a similar effect on us again.

It is easy to say that our environment has obviously played a part in our evolution. Being able to pin down the exact reasons why through historical analysis helps to deepen our understanding of what exactly was happening in major times of our evolvement and what our responses were to our changing environment. These articles are able to give us a more detailed record of how our evolution has irrevocably changed our environment, and vice versa. Not only did this widespread destruction start longer ago than previously believed, but it also shows how they may have altered us in return. The work done by these writers can be recreated and the possibility of more information to further prove or counter this is widely accessible through fossil records and timelines. There is a strong correlation between our damage to the environment through evolution and our evolutionary changes based on said damaged environment.

Caperton Morton, Mary. "Hominid vs. Hominin." EARTH Magazine. August 18, 2016. https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/hominid-vs-hominin

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. "Media Release: Nature's Dangerous Decline 'Unprecedented'; Species Extinction Rates 'Accelerating'." IPBES: Science and Policy for People and Nature. May 6, 2019. https://www.ipbes.net/news/Media-Release-Global-Assessment.

Kirch, Patrick V. 2005. "ARCHAEOLOGY AND GLOBAL CHANGE: The Holocene Record." Annual Review of Environment and Resources 30: 409-440. http://libraryaccess.sdmiramar.edu:8080/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libraryaccess.sdmiramar.edu/docview/219877856?accountid=38871.

McKee, Jeffrey, Julia Guseman, and Eric Chambers. "Ohio State News." Outlook Is Grim for Mammals and Birds as Human Population Grows. June 18, 2013. https://news.osu.edu/outlook-is-grim-for-mammals-and-birds-as-human-population-grows/.

Potts, Dr. Rick. "Climate Effects on Human Evolution." The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program. September 14, 2018. http://humanorigins.si.edu/research/climate-and-human-evolution/climate-effects-human-evolution.

Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E., Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Roger B. Beck, Jerry Dávila, Clare Haru. Crowston, and John P. McKay. A History of World Societies. 10th ed. Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Bedford / St. Martins, Macmillan Learning, 2018.

Hello! I'm a Michigan native; born and raised in Mid-Michigan. I am 22 years old and I am married; I've known my husband since 7th grade. Before I started going to college, I wanted to be a baker and even took serious steps in that path before switching gears. I am in my final semester before I graduate with my Associates Degree in Business Administration and transfer to San Diego State University. I love doing anything that involves being outside, as long as I can take my dog—Nora—with me. She’s my partner and crime, along with my husband and we love being active and getting out whenever we can. Being here in San Diego has given us so many opportunities to explore this beautiful place and we love it. We always take the opportunity to enjoy it while we can!

The concept of where we get our traits and characteristics from traditionally is relatively simple to understand. In many schools, kids are taught the basics of genetics starting as early as third to fifth grade. If you ask any of these kids to tell you where they get their curly brown hair or their bright blue eyes, they would probably give you the same answer as many adults who have a similar level of understanding of the concepts—mom and dad of course! The concept of inherited traits is not only easy to understand, it also makes sense and is backed by scientific research. However, the widely accepted genetic inheritance process may not be as clear cut as we originally believed.

When we think about genetics, the familiar species tree concept often comes to mind. In following the branches, we can trace species back through their genetic characteristics that have been passed down to them through reproduction. It also follows that these traits change according to different circumstances over long periods of time through the evolutionary process. All of these traits can be visualized as being passed on vertically from parent to child over generations.In this paper, I will be discussing the concept that challenges this idea and gives new life to the ideas of evolution and adaptation. This concept has changed the way that scientists view genetics and it has a bright future in a variety of different fields of research.

More recently, scientists started to notice that not all adaptations seemed to follow this pattern of vertical structure. Research indicates that genetics can move vertically but also horizontally as well. This concept is called lateral gene transfer and has made big waves in the field of genetics as it has challenged the entire idea of the tree of life. Even though the idea that genetics flows in both directions has met great resistance throughout its history, the future looks promising for the study of lateral gene transfer.

In 1928 the possibility of genes being able to transfer horizontally was first observed in an experiment by Frederick Griffith (Quammen, 2018). The results Griffith found through his experiments were alarming, and he wasn’t exactly sure what to make of them.

In one experiment, for instance, he injected heat-killed S form (virulent) of Type I bacteria along with living R form (mild) of Type II bacteria into five mice. When all five keeled over within a few days, and Griffith drew blood, he found living Type I that was virulent. Note again this change: dead virulent I, plus living mild II, becomes…living virulent I. Something weird had happened. It sounded like zombie bacteria. Either the mixing had brought the virulent Type I back to life, or else the dead Type I had somehow transformed the living Type II into a version of itself. This wasn’t a sci-fi movie, and neither of those options was supposed to be possible. (Quammen, 217)

Scientists started noticing that bacteria could absorb the genetic material of dead bacteria essentially by consuming them. This came as a surprise to scientists who had previously accepted the vertical theories of genetics. was later discovered by a scientist named Joseph Lederberg that two bacteria could also share genetic material by “mating” with each other, thereby exchanging their differing traits. For example, if one bacterial organism had a trait X and “mated” with a bacterial organism with trait Y, it was observed that both bacteria had traits X and Y after the exchange. This concept of course seems ridiculous in that sense which is part of the reason the idea was so widely rejected early on. It seemed absurd that two organisms could exchange genetic material this way. This concept is called conjugation.

An example of conjugation can be seen in examining the rapid rate in which bacteria build up a resistance to antibiotics. Through a concept called infective heredity, bacteria can exchange resistant genes very rapidly with each other. These resistant genes are called episomes and can be copied and exchanged between bacteria quickly, reducing the effectiveness of antibiotics (Quammen, 2018).

An important topic that scientists are currently exploring is what the future of lateral gene transfer might look like. The impact of lateral gene transfer in nature in the future may be difficult to predict or speculate beforehand. Fortunately, scientists are now taking lateral gene transfer into their own hands by replicating the process artificially under lab conditions, removing all unwanted outside factors. In an article from Cell Press, the authors write that "the natural process of horizontal gene transfer can be mimicked under laboratory conditions. In plants, transposable elements of the Ac/Ds and Spm families have been routinely introduced into heterologous species” (IVICS, 1999). Basically this means that experiments are being done in controlled lab environments to find the applications and potential limits of lateral gene transfer.

In essence, much of the gene editing that is being researched and studied today also falls under the umbrella of lateral gene transfer. Huge strides are being taken in the realm of taking genetic code from one organism and transferring it horizontally—as opposed to traditionally vertically—to achieve certain desired genetic outcomes. This raises the question of ethics in genetic modification today. Although synthetic lateral gene transfer can have seemingly minor results compared to other forms of genetic engineering, it is still important to visit and research the various standpoints in the debate of ethical genetic modification.

Genetic modification has had a history of receiving a very volatile reaction since its inception. When stem cell research was first brought into the scope of the popular media, it met very strong resistance due to the source of the stem cells, one of the few available at the time: “the controversy was much worse a decade ago when the major source of stem cells was aborted fetuses” (Schoenberg, 2019:2.4.4.2). Today there are far better options for harvesting stem cells such as “from your own baby teeth, your blood, even from your leftover liposuction” (Schoenberg 2019:2.4.4.2) which has increased the support for this controversial topic. As the technology starts to catch up with the seemingly far-fetched ideas of the possibilities of genetic modification, the conflict between the two sides in favor of it and against it grow more and more relevant. These topics of debate no longer deal with vague, hypothetical “what-if” scenarios but real “what-happens-when” scenarios. These new advancements and discoveries will open many doors for the biological and anthropological communities, regardless of their mixed reception.

Until laws are made preventing genetic modification, it is only going to grow larger and more powerful. This means that synthetic lateral gene transfer has a promising future for its study and application. In revisiting the topic of bacterial resistance to antibiotics, imagine the applications of reverse-engineering the process by which this happens. If scientists could use what we now know about lateral gene transfer to come up with a solution for this problem, it would have enormous effects on the pharmaceutical industry. This is only one of an infinite number of potential applications that should be considered and researched further.

Lateral gene transfer is a radical idea that has challenged the almost unanimously accepted previous concepts of genetics and the tree of life. The history of the study of horizontal genetic flow was unpopular and controversial. Nevertheless, the few who did chase and study this idea have made huge strides in completing our understanding of genetics. Although the examples of lateral gene transfer observed so far may seem insignificant, they open the door to an unlimited potential for genetics.

Kaiser, Jocelyn. “U.S. Panel Gives Yellow Light to Human Embryo Editing.” Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 14 Feb. 2017, www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/02/us-panel-gives-yellow-light-human-embryo-editing.

Quammen, David. The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life. Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Schoenberg, Arnie. 2019. Introduction to Physical Anthropology. Arnieschoenberg.com/anth/bio/intro/index.html

Zhaxybayeva, Olga, and W. Ford Doolittle. “Lateral Gene Transfer.” Current Biology, Cell Press, 11 Apr. 2011, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982211001011.

Ivics, Zoltan. “Molecular Reconstruction of Sleeping Beauty, a Tc1-like Transposon from Fish, and Its Transposition in Human Cells.” Cell Press,14 Nov. 1997, https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(00)80436-5?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0092867400804365%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

My name is Andrew Hinshaw. I grew up in the Bay Area but I came down to San Diego a few years ago for school. I had completed four years at California State University San Marcos but had to take a temporary leave of absence. I will be attending San Diego State University starting this fall to finish my degree in Computer Science. In the meantime, I'm happy to be here at City College picking up my last few general education classes before I go back to finish my degree. I'm currently working full time doing customer service for an software company and enjoying getting to see all the inner workings of a rapidly growing small business. My goal some day is to run a business of my own so I am learning all that I can now to set myself up for success in the future.

Although I have a limited background in anthropology, I enjoy learning about anything and everything. Some of the topics in the scope of anthropology are fascinating to me and I hope to be able to explore them deeper in the future.

In 2017, Malaria caused approximately 435,000 deaths worldwide (WHO, 2019). This number represents approximately 30% decrease from the year 2010 and continues to decline. While the number of deaths has dramatically decreased in the past 20 years, preventing contraction of the disease has been challenging. In 2017, approximately 219 million cases were reported, a steady number over the past ten years. Historically, approximately 90% of these deaths occurred in Africa, but in the age of globalization, there is a high risk for the disease to occur and adapt in new environments (WHO, 2019). The production of the genetically edited mosquito is theorized to end the malaria-carrying mosquito population, but there remain many ethical issues and theoretical problems with such a release. Mathematical models and lab testing have had individual successes with gene drives (Selfish gene, Driving-Y and population replacement) that researchers believe have the capability to collapse mosquito populations. Though, gene drives in mosquito populations have proven successful in the lab, the ethical implications of employing this approach in malaria prone communities will be a challenge. This can be overcome by using a consistent, aggressive and community-oriented approach to ultimately eradicate malaria.

In 2018, gene drive research was nearly driven into a moratorium at the annual convention for biological diversity held in Egypt (Callaway, 2018). Members ultimately denied a moratorium on gene drives, instead imposing limitations on the research, citing a need for caution (Callaway, 2018). Gene drives are a method of suppressing or eliminating a trait within a certain population. In natural Mendelian inheritance, when two parents mate, the chance of the offspring having a certain gene is around 50% (Callaway, 2018). With modern gene-editing technology, scientists can edit or completely remove a gene in a subject species. Once released into the populations, due to the careful editing process, the offspring of these subjects have a 100% chance of carrying the edited trait (Callaway, 2018). One of the main arguments for proponents of gene drive technology is that it is the most efficient and cost-effective tool against eradicating diseases, such as malaria (Callaway, 2018). Malaria is a disease that is transmitted in over 200 million people per year and resulting in nearly half a million deaths annually, many of which occur in children under the age of five (WHO n.d). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2019) is committed to helping communities receive preventative measures such as treated bug nets and vaccinations (WHO, 2019). Though, many experts believe that the organization are far from attaining their goal of 90% eradication of malaria by 2030 from these methods alone (Eckhoff, 2017).

Although great success in reducing the burden of malaria has been achieved with current tools (2), the remaining burden is intolerably high, and significant questions remain about how much further these already deployed tools can get to elimination (28–30). On the horizon, there are ways to use drugs and diagnostics in innovative campaigns to clear the human infectious reservoir (31), potential rollout of vaccines (32), coverage increases with existing tools (2), and more, which could get closer to elimination. However, it will require high levels of effort and funding just to maintain current gains. [Eckhoff, 2017]

CRISPR (proper name, Clusters of Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) systems have already shown success is lab tests around the world for utilizing gene drives to advance elimination the malaria carrying gene in Anopheles mosquitoes. CRISPR Cas9 systems work by tying together “RNA” molecules to create a marker for cutting within a particular sequence (Vidyasagar, 2018). The system then cuts through the entire DNA strand to either remove a part, or allow for the sequence to repair itself, thereby changing signals within the subject species (Vidyasagar, 2018). This technology allows for scientists to target specific genes and either modify or eliminate traits in an organism (Broad Institute, 2018). However, it is important to compare current studies to identify the true risks and benefits between lab tests and wild populations. Due to a lack of public insight on the benefits of implementing gene drives (Callaway, 2018) one bad test could cause these systems to lose credibility with the public on a global scale, making a moratorium on this research more probable. Through analysis of mathematical models, lab testing, and wild population testing, this literature review will compare the use of gene drives in tests in Panama, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Italy to compare commonalities of benefits and risks. To ethically release gene drives to eradicate malaria, these factors must be identified in order to fully educate communities and prevent reintroduction of the disease in the future.

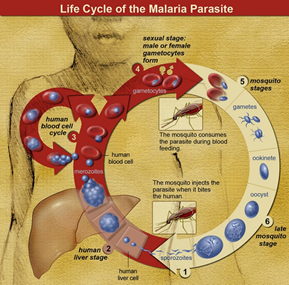

The battle with malaria has existed in human history for centuries. The parasite Plasmodium is the root cause of disease transmission from mosquito to human (Schoenberg 2019). Infection occurs when the parasite enters the bloodstream and reproduces, causing cells to pop and continuing infecting cells causing severe or fatal sickness (Schoenberg, 2019).

Infection begins when (1) sporozoites, the infective stages, are injected by a mosquito and are carried around the body until they invade liver hepatocytes where (2) they undergo a phase of asexual multiplication (exoerythrocytic schizogony) resulting in the production of many uninucleate merozoites. These merozoites flood out into the blood and invade red blood cells where (3) they initiate a second phase of asexual multiplication (erythrocytic schizogony) resulting in the production of about 8-16 merozoites which invade new red blood cells. This process is repeated almost indefinitely and is responsible for the disease, malaria. As the infection progresses, some young merozoites develop into male and female gametocytes that circulate in the peripheral blood until they are (4) taken up by a female anopheline mosquito when it feeds. [Cox, 2010]

Figure 1: "Life Cycle of the Malaria Parasite" by National Institutes of Health 2009 (Public Domain)

The United States went through nearly a century focused on the eradication of entire mosquito populations, not considering the complexity and resistance of the disease (Patterson, 2009:9). Throughout the 1900s, in the United States, predominantly white, middle-class groups of people launched campaigns focused solely on the eradication of entire mosquito populations. However, these campaigns had less to do with disease control and more to do with eliminating “nuisance pests” in hopes for higher property values. To deter mosquitoes, communities created drainage ditches to eliminate stagnant water areas. In 1942, the use of insecticides became the predominate factor to mosquito control, as more soldiers were sent overseas and came back home. As insecticides became more popular, past preventative measures were abandoned for what appeared to be a more viable prevention tool. The use of intense chemicals as a preventative method harmed many ecosystems. Furthermore, reliance on this method resulted in a severe lack of community education as mosquitoes became more resistant to the insecticides (Patterson 2009:9-10). The failure of these campaigns to eliminate malaria, the global will to eradicate malaria declined significantly and instead placed priority on malaria control. While some countries have managed to eradicate malaria from their countries effectively with current preventative methods, other countries continue to struggle severely with this disease (Shah, 2010). In 2007, the Gates Foundation reignited the eradication campaign and empowered the World Health Organization to join in the eradicate malaria campaign (Shah, 2010). One of the few species who do carry the malaria trait are the female Anopheles population. Current preventative methods have shown a dramatic decline in the transmission rates and resulting death rates in the past 20 years, but these results are now reaching a plateau as these mosquitoes become vaccine and insecticide resistant (Matthews, 2018).

In 2012, CRISPR brought gene drive theories to reality (Esvelt, 2017). Not even 10 years after its’ invention, gene drive testing is creating successful results in the lab and at an impressive rate (Esvelt, 2017).

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) genome editing has catapulted prior theoretical speculation into reality, at least in the laboratory [9, 10]. Encode a desired genomic change along with the components of the CRISPR system, and it will cut and replace the original sequence with the new version in each generation. [Esvelt, 2017]

Despite these lab successes, there remain many ethical considerations regarding this technology. One ethical consideration of gene drive is that utilizing gene drives will attract unintended consequences in the local ecosystems (Esvelt, 2017). One argument is that gene drives that “self-propagate” will inherently cause the species to be “highly invasive” in the local and neighboring ecosystems by spreading to untargeted species (Esvelt, 2017).

Another consideration against gene drive use in mosquitos is that “a slippery slope” effect will ensue (Neves, 2017). Nearly new biotechnologies in the past half century have seen some form of this “slippery slope” effect with positive and negative consequences (Neves, 2017). If gene drives can surpass these ethical implications, who determines what other insect or animal populations see the use of these gene drives, and how can regulations deter scientist of nefarious testing (Matthews, 2018)? Companies around the world are currently testing gene drive methods to determine sustainability of such powerful technology and identify issues in testing.

There are a few gene drive methods that researchers hypothesize will eliminate or replace malaria carrying mosquitos. The “Selfish” gene, in which a gene is edited to interfere with the fertility in the population, “driving-Y” in which x chromosomes are impacted, causing mosquitos to have male offspring, eventually eliminating, or “collapsing” the entire population in the local area. One of the more popular methods for testing is the Selfish gene drive relies on releasing sterile males into the population. With this method, population eradication seems likely as female mosquitoes in the locality will not be able to reproduce.

Through mathematical model researchers simulate vector control in 2 Sub-Saharan regions, Namawala District in Tanzania, the Garki District in Nigeria. Each of these regions provide high vectors of mosquitos as well as significant weather data that contain a large enough sample size to test the parameters (Eckhoff, 2017). Over a thousand parameters are used to simulate the three commonly proposed gene drives. Parameters include characteristics such as seasonal weather, feeding and fertility patterns of the An. Gambia population. In conjunction with gene drive release, the models consider a random variable known as a “nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) “wild type” allele that persists when a gene is not fully “cleaved and repaired” within the gene drive release. This wild allele can become resistant to further gene editing, and in the worst-case scenario, the mosquito population returns with the gene-drive resistant gene intact. This study differs from previous studies that focused on “single larvae” habitat which produced more skewed results, as there are typically many more than one larvae habitat in a locality. To produce more realistic results, approximation is used to place a fixed mortality rate parameter (Eckhoff, 2017).

The model used in this manuscript assumes there are many small habitats across the landscape that add up to the time-varying larval capacity in the basic model (22). Rather than tracking many small habitats, which would be very difficult to parameterize or localize, a “many-puddle” approximation is made. Eggs laid into a small habitat in which there will be fourth-instar larvae while the hatched eggs are first-instar larvae are deemed to have much higher mortality. Thus, a saturation function is applied for each day’s closed-loop egg laying; the higher the local larval population relative to the patch’s larval carrying capacity, the more the number of viable eggs laid is reduced. [Eckhoff, 2017]

These studies found that seasons will dramatically affect the advantages of gene drives (Eckhoff 2017). Each region has different weather patterns that will determine the effectiveness for gene drive release. The “dual-germline” testing models found that an extremely dry season, vector models show that releasing gene drives will suppress the population enough to dramatically show growth by the start of the wet season. In more consistent weather, the population control does not show as much of a significant decline. In the Driving-Y testing models, the models showed that if more males are born with only the Y gene, population collapse could be seen within 8 years. Of note, one model run presented a scenario in which all male mosquito had the only the Y gene, but enough wild females were born to be able to sustain the population (Eckhoff, 2017).

In cases of severe seasons, such as the Garki District in Nigeria, the models showed extreme seasons will be a challenge to implementing gene drives (Eckhoff, 2017). The mosquito population is sparse in the dry season, so implementing gene drives in this time frame has a higher risk of missing pockets of wild mosquitoes that will sustain the population in the wet season. The researchers suggest that these challenges can be overcome by a calculated and “aggressive” gene drive release strategy (Eckhoff, 2017).

The Target Malaria campaign is currently testing its gene drive Anopheles mosquitoes in secured labs (Target Malaria, n.d) There are two gene drive strategies being implemented in their lab. The first gene drive method is to modify mosquitos so that at least 90% of the population is male (Driving-Y method). Genetic alterations of the X gene in the male mosquitoes requires that its’ offspring will only inherit the functioning Y-gene, therefore suppressing the female Anopheles population. The second focus is to reduce fertility of the Anopheles female. This method involves ensuring that an altered female mates with an altered male and receives a duplicate copy of the altered gene, subsequently making her infertile (Target Malaria n.d.).

In a 2018 small scale study, researchers part of the Target Malaria campaign sought to identify the if the dsxgene in Anopheles would advance the goal of population infertility (Kyrou, 2017). Utilizing Cas-9 CRISPR systems to target the dsx allele, two cages were tested containing both wild type mosquitoes from Sub-Saharan Africa and genetically altered lab mosquitoes. By generation 8 in Cage 1 and generation 12 in Cage 2, infertility was gained at 100% and successfully collapsed the mosquito populations. Resistance to this gene drive was not found by researchers, however they note that larger scale testing needs to be done to determine the validity of this finding (Kyrou, 2017). Until gene drives can guarantee resistant-free mosquitoes, collapsing or eliminating permanently will prove a significant challenge (Calloway, 2018).

The mathematical models, as well as the small-scale lab testing, show efficient and quick population collapses in the Anopheles mosquito populations. In both studies, the Driving-Y method of gene drive release have similar contributions to population collapse. Both studies point to the need for further testing in the field to determine real successes, but they lay important groundwork for field testing once approval can be gained. One of the weaknesses that the studies do not include is how these finding will translate to high risk communities who will be on the receiving end of any field trials supported by these studies. This will be important to the sustainability of successful population collapses.

As of 2016, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), who has regulation authority over genetically engineered mosquitos, has approved field testing for the company Oxitec to pursue gene drive release into wild mosquito populations in Florida (Meghani, 2018). However, the proposed field trial from Oxitec to the FDA is controversial. Opponents of Oxitec’s application argue that regulatory practices by the FDA are not effective towards this rapidly evolving technology. Of note, risk assessment of the local ecosystem effect from the multiple releases that Oxitec’s altered mosquito would need to support the gene drive. Researchers stress that regulatory agencies need to evaluate their risk assessment in order to provide transparencies to the communities who receive the gene drive (Meghani, 2018). At the time of this paper, no significant field trial data have been published for peer review.

Overwhelmingly, there is a clear consensus that use of gene drives in mosquitos is the quickest and most cost-effective measure towards eradicating malaria. It is likely that this research will once again be up for debate within the United Nations in the years to come. Gene drives are humanity’s best chance at eradicating malaria, but we must proceed cautiously and with full informed consent of the communities who are directly affected (Matthews, 2018). As the CRISPR systems are less than a decade old at the time of this paper, there is at least one thing that both proponents and opponents agree on, scientists must be able to guarantee that these systems will work without consequence and without reintroduction or increased spread of disease (Neves, 2017). The lack of testing of gene drives in wild mosquito populations remains the weakness of every lab test that proves success. Unfortunately, there is not yet enough published and peer-reviewed field data to determine viability of these methods in a wild population (Neves, 2017). Time is of the essence with millions of people suffering from malaria each year, however, it is not ethical to release gene drives into a locality until there has been enough testing done outside of lab scenarios, as well as significant community education in the localities where CRISPR mosquitos will be released. In conclusion, gene drives are showing potential for real population collapse. Based on current lab testing a more aggressive and regional approach to release strategies will be necessary for the most efficient and cost-effective use of gene drives on Anopheles mosquitoes and ultimately eradicate malaria.

Achenbach, Joel. "'Gene Drive' Research to Fight Diseases Can Proceed Cautiously, U.N. Group Decides." The Washington Post. November 30, 2018. Accessed March 21, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2018/11/30/gene-drive-research-fight-diseases-can-proceed-cautiously-un-group-decides/?utm_term=.8f2d9f85d463

Questions and Answers about CRISPR." Broad Institute. August 04, 2018. Accessed April 19, 2019. https://www.broadinstitute.org/what-broad/areas-focus/project-spotlight/questions-and-answers-about-crispr