Spring 2023 San Diego Community College Student Anthropology Journal

Edited by Arthur Flores

Cover Illustration by Brandon Estrada

Published by Arnie Schoenberg

http://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/journal/spring2023

Volume 7,Issue 1, Spring 2023

latest update: January 29, 2024

Unless otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

More issues at http://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/journal/

contact: prof@arnieschoenberg.com

Anthropology is a field that looks at human culture holistically, taking all the different aspects and subfields of anthropology to form a whole a view. Ethnology specifically observes the characteristics, relationships, and actions of peoples and the reasons behind them. For example, as will be discussed in this article, why we play certain games and how we adapt them to changing factors within society, and whether those games are part of spiritual beliefs or used for conflict resolution.

The Trobriand Islands off of New Guinea is one of many places that dealt with British colonization and adapted in certain ways in order to retain some of their identity. A specific example would be the adaptation of cricket; an iconically British game brought to the islands by the colonizers. The indigenous tribes took the game and made it their own, as they themselves declare that the game is now theirs. Over time, the game replaced their tribal battles and military traditions, something seen as positive by many Western thinkers and colonialists. But this could also be seen as a loss, a cultural loss that allowed them to become easier to dominate and colonize. Yet the fact that some of the traditions and customs were transferred into the context of the game instead of battle shows how not all was lost and perhaps if it had not been for the game, those traditions would all have been lost entirely (Leach and Kildea 1976).

The fact that the games and customs no longer have a clear connection to a long historical context, shows that all indigenous peoples put up a fight in different ways. The Trobriands turned a recreational game that was basically forced upon them into a ritualistic and political tool, one of conservation and agency to keep some form of their ways from completely dying out. Had the Trobriands not done this, it is very likely that rituals and characteristics of their culture would have been wiped out violently by the British Empire as was done to countless others.

Like the Trobriand Islands, the Americas were also colonized and culture was violently repressed by the Spanish. Of course other nations colonized many parts of the Americas but Spain was responsible for the areas where an ancient Mesoamerican ball game was played. The ball game had political and militaristic significance, and it was heavily religious and ritualistic (Aguilar-Moreno 2014). The Spaniards, seeing it as demonic, foreign, and another obstacle to their rampage of colonization and evangelization, banned it. The games were connected to observations about planetary movements and in turn of myths and religious beliefs of these civilizations. Its different aspects and rules were reflective of beliefs about the underworld, fertility, and the duality of nature and the cosmos. Many human sacrifices were determined by the game’s outcome, and in some places players actually competed to be sacrificed, while in others the losers were sacrificed. Most ball games included the concept that blood is like rain and is needed for the world to continue as we know it. It was also a link between cities and empires, one of political processes, status and storytelling so that religious beliefs and myths could be performed (Aguilar-Moreno 2014). The ball game has been revitalized to a certain degree since colonization, but many have transitioned into playing it somewhat secularly.

The contemporary players of the game can be grouped into 1) those who played because of a long line of playing it through the context of colonialism, or 2) those who are reviving it because of their desire to strengthen and rescue the game, and play it as close to its original pre-colonial context as possible. There are also the ones who transition from the first group into the second; the letting go of colonizing beliefs, something that is healing and further connects them to ancestors (Aguilar-Moreno 2014).

Comparing sports in Mesoamerica and the Trobriand Islands shows different ways of resisting colonization and with each indigenous group we find they have various ways of keeping their own identities alive and refusing to allow history to put them in a passive light. There is outright fighting back against an imperial force that wants to eradicate you, and there are the more nuanced and subtle ways of taking what is put upon you and infusing yourself into it, even if it means some of you is lost to save the majority.

Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel. 2014. Ulama: Pasado, Presente Y Futuro del Juego de Pelota Mesoamericano. California State University, Los Angeles.

Hasty, Jennifer, David G. Lewis, and Marjorie M. Snipes. 2022. “Chapter 19: Indigenous Anthropology.” Introduction to Anthropology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/introduction-anthropology.

Leach, Jerry and Gary Kildea. 1975. Trobriand Cricket. Journeyman Pictures TV.

Stuart Gieger, R. 2006. Trobriand Cricket: An Indigenous Response By Colonialism. Creative Commons.

Andrea Vega Marshall is a Mexican-American student born and raised in San Diego, California, and is currently attending San Diego City College to transfer to Cal Poly Humboldt and major in Tribal Forestry, and potentially minor in Wildlife Conservation. The natural world and its inhabitants has always been a passion for her and she hopes to make it a career, one that involves minimal cubicles and computer time. Subjects like the one written about here have always been of interest and importance to her, and she hopes to help in the fight to make sure tribes and indigenous get the sovereignty and agency that is rightfully theirs. She is a lifelong student, artist, and reader.

Confronting mortality is a defining aspect of life, both on a micro-level involving individual experience, and on a macro-level referring to a larger cultural context. Death is a universal experience–an equalizer–and this implies a universal emotional impact. These emotions could include introspection, grief, or ease. Here I will compare two articles: “Introduction: Grief and a Headhunter’s Rage”of Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis” by Renato Rosaldo (1993) and “Exploring Contemporary Forms of Aid in Dying: An Ethnography of Euthanasia in Belgium and Assisted Suicide in Switzerland” by Natasia Hamarat, Alexandre Pillonel, Marc-Antoine Berthod, Dolores Angela Castelli Dransart and Guy Lebeer (2022). These texts include ethnographies on the subject of death, including both the process of aid in dying and the process of killing. While death marks the end of physical life, death can also initiate an emergence of consciousness for life. I will argue that death enables a conscious analysis of emotions to gain a greater sense of existence. While death has marked the whole history of humanity as a consequence of conquest or war, it is also perceived as a state of transition or as a journey towards an afterlife. For example in my own Mexican Culture, Día de Muertos is observed as a celebration to remember those who have passed. It can also be seen as a mockery of death, or more recently the plot of a Disney movie. Within my Catholic upbringing, death is seen as a price for sin and part of the passage towards heaven, purgatory, or hell. The connections between death, punishments, and consciousness enable cultural practices to form and become fixed. In “Introduction: Grief and a Headhunter’s Rage”of Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis”, Renato Rosaldo re-conceptualized the emotional force of death as it pertains to Ilongot headhunting. He analyzes his observations within a new framework that aims to be critical of the position and reposition of the subject in relation to the culture in the environment. In “Exploring Contemporary Forms of Aid in Dying: An Ethnography of Euthanasia in Belgium and Assisted Suicide in Switzerland”, two major case studies involving fieldwork from assisted suicide in Switzerland and euthanasia in Belgium are used to focus on the processes of normalization that structure aid in dying.

Independent of the context of any particular cultural background or belief system, the impact death can cause by loss of a loved one or the ability to live life as one anticipated creates profound and complex emotions. Experiencing grief and anger as a result of death can last for a long period of time. Renato Rosald hypothesized that rituals, with an emphasis on Ilongot headhunting, model a synchronization of multiple coexisting social processes (Rosaldo 1993, 172). “Exploring Contemporary Forms of Aid in Dying” (Hamarat et al. 2022) compares the individual experiences of those who are involved in the process of assisted suicide in Switzerland and euthanasia in Belgium. Both European ethnographic studies were able to illustrate the intricate personal social and ethical aspects that contribute to these controversial medical operations. Head hunting could be viewed as a ritual, although lacking the structure of planned anticipation. It serves as an important marker of social identity among the Ilongot. Headhunting is an outlet for mourning (Rosaldo 1993). Within the structure of western society, killing is frowned upon. However, considering the history of genocide and conquest, along with modern day war and economic and military occupation for the sake of globalization, it would be hypocrital to view this practice as “uncivilized” or “incomprehensible”. Renato Rosaldo proposed that rituals, with an emphasis on Ilongot headhunting, model a synchronization of multiple coexisting social processes and Rosaldo supports the hypothesis through the reexamination of his previous understandings with a new framework that resulted from his own personal experiences with the emotions of loss through death (Rosaldo 1993, 172). Death causes such a strong emotional reaction partly because it provides the opportunity to confront mortality as well as the nature of fragility for human life. It enables people to question the purpose and meaning of existence.

The perception and emotional experience of death by an individual or group depend on social frameworks, and in the case of the ethnographer, is influenced by their methods. The method for Hamarat’s (2022) research consisted of comparing large scale fieldwork surrounding euthanasia in Belgium and assisted suicide in Switzerland. This was able to offer insight on different cultural contexts and different legal frameworks. As a result there was a deeper comprehension of the influences to the implementation and execution of aid in dying practices. Death can be accepted as a natural part of life or as a tragedy. “Euthanasia” in Belgium and “assisted suicide” in Switzerland are replaced with the general term “aid in dying”. This allows for a comprehensive center to analyze both cases of field work. Within Western society, death gets viewed through a medical perspective, where there is a categorization based on diagnosis, treatment, or subject of study. This process often excludes the emotional consequences, and will devalue the emotional impacts. Hamarat’s hypothesis is that normalization consists of a process that is partially attributed to the current legislation, which underlies the relationships that are formed between those seeking aid in dying and the healthcare staff, volunteers, and loved ones (Hamarat et al. 2022, 1593). Through an examination of the diverse elements that make up the personal experiences, the practice, and the legal frameworks, this article is able to offer an awareness of the process of aid in dying. Renato Rosaldo also emphasizes personal experiences, specifically the death of his wife, Michelle Rosaldo. They lived and conducted field research in the upland area about 90 miles from Manila, Philippines. The Ilongots had a population of 3,500 and lived in an upland area that is about 90 miles northeast from Manila, Philippines. Their participation observation lasted 30 months between the years 1967, 1969, and 1974 (Rosaldo 1993,167-168). Renato Rosaldo analyzes his observations within a new framework that aims to be critical of the position and reposition of the subject in relation to the culture in the environment. To achieve this Rosaldo returns to his field notes and redefines his data after experiencing death, rage, and grief in his personal life (Rosaldo 1993, 172). Each specific experience in participant observation with individuals who have direct active roles in the process of aid in dying is specific to a particular region, and the individual expression has a cultural context.

I hypothesize that situations of death enable a conscious analysis of emotions to gain a greater sense of existence, aid in dying exhibits a different approach and there is an extensive comprehension of one’s own life and the emotions surrounding their life and ultimate decision for death. Empirical data is exclusive to a certain area but under particularly similar circumstances and it points to a broad commonality that highlights new paradigms for aid of dying in the contemporary term (Hamarat et al. 2022, 1593). Although this is able to offer insightful unique accounts, it could be seen as lacking in sufficient evidence for an extensive social analysis for aid in dying, death, or grief. Medical statistics usually include: excerpts from dialogue observed in the field work, the legal process for a patient to complete the aid in dying process, and patient stories. This is the foundation for a focus on an exploration of the contemporary forms of aid in dying and its processes of normalization. Situations of death enable a greater sense of existence and deciding that the patient has experienced a fulfilling enough life to choose to end it. As religion is universal, it can be considered too abstract to condense into a singular definition. However it is a crucial aspect of humanity to understand as religion is intrinsically social (Hasty, Lewis, and Snipes 2022,13.4). In reference to the Ilongots, the practice of headhunting involves symbolism as through the process of decapitation, tossing a head also carries a sense of throwing away the emotions of grief and rage that accompany experiencing death. The Ilongots do not keep the heads as a trophy, which can be indicative of a sacredness to process emotions and continue with life (Rosaldo. 1993,174). The emotions surrounding decisions about death help us gain a greater sense of existence.

In conclusion, the emotional impacts of death are complex, profound, and universal. Death has important impacts on the emotional process that is required to have a conscious analysis to gain a deeper understanding of existence. There are diverse ways to process death based on individual and cultural frameworks. These case studies offer insights to a collective process of death and applied to define the new paradigmatic forms to aid in dying in the contemporary era (Hamarat et al. 2022,1604). Through re-evaluation of shared experience, Rosaldo was able to recognize that rage is born of grief and headhunting allows the Ilongot to carry the anger (Rosaldo. 1993,167). Although there is a wide range of emotional responses, grief and loss impact all humans. These experiences of emotions unite all people. Although death calls for the end in human life, there is an opportunity to explore and connect to elements of existence.

Hasty, Jennifer, David G. Lewis, and Marjorie M. Snipes. “Religion and Culture .” Introduction to Anthropology. Houston, Texas: OpenStax, 2022. Introduction to Anthropology | OpenStax.

Renato Rosaldo, ‘‘Introduction: Grief and a Headhunter’s Rage,’’ in Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis (Boston: Beacon Press; London: Taylor & Francis, 1993), 167-178. 15 Grief and a Headhunter’s Rage

Hamarat, Natasia, Alexandre Pillonel, Marc-Antoine Berthod, Dolores Angela Castelli Dransart, and Guy Lebeer. “Exploring Contemporary Forms of Aid in Dying: An Ethnography of Euthanasia in Belgium and Assisted Suicide in Switzerland.” Death Studies 46, no. 7 (2021):

1593–1607.https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/07481187.2021.1926635?needAccess=true&role=button.

I am Verenice Arroyo, a student at San Diego City College. I am double majoring in general business and anthropology. Due to the opportunity of taking college classes while in highschool, I was able to get a head start in my higher education. My initial curiosity to pursue a career in Anthropology started with a professor I had for a Chicano Studies course who was a doctor in anthropology. Next I took Anthropology 102 and my interest deepened. I am eager to learn as much as I can from this course. My goal would be to work as a museum director.

Small local businesses serve an integral role in their community, benefiting the local economy and influencing the culture they are a part of. Restaurants are one of the most common local businesses. Lola’s Bistro and Bakery, the restaurant I work at, is a key part of the community in the town where it serves. The dedicated individuals who work at Lola's are the driving force behind the restaurant's success and good reputation. Despite the positive and successful work environment that has been structured here, I have noticed inconsistencies with the staff that have caused the business to suffer. The tight-knit community and family dynamic that exists is what I think opens the possibility for some employees to disregard policies and not take things ‘too seriously.’ I hypothesize that family owned businesses suffer from inconsistencies in the work ethic between management and staff. The comfortable, less demanding environment of Mom and Pop restaurants encourages staff to take a more relaxed approach to their work, resulting in oversights or overlooked details.

As an active employee working shifts at the Lola’s Bistro and Bakery, I took time to observe the moments I was living through and also took notes on days I was not scheduled, to try to notice things from a different perspective. I also observed moments in our all-staff meetings, which included Mary, the owner. In addition, I referenced three sources; an anthropology textbook by Jennifer Hasty (2023), a thesis by Amanda Shigihara (2014) titled “A ‘Professional Backplace’: Ethnography of Restaurant Workers”, and a recording of a TED talk presented by Aaron Silverman (2019) titled “How I built the number one restaurant in America.”

Anthropology is best known as the study of humans. Specifically, their development and the evolution of culture. Cultural Anthropology is one of the four main subfields of anthropology. There is a subdiscipline known as ethnography which focuses and interprets today’s cultures (Harris and Johnson 2007, 2). In this ethnography, I will discuss the culture that has developed in my workplace and the role organizational culture plays in the work environment. Organizational culture is the social structure of a business and the interactions of the staff.

I observed the relationships, interactions, and behaviors of my coworkers and determined that these all contribute directly to the culture that has been defined at Lola’s in recent times. Mary’s restaurant has always had a family dynamic and tight community within it. Starting with the vocabulary used at the restaurant - “Front of House” and “Back of House” to differentiate positions and responsibilities. Despite the titles of front or back, because it is a small business we are all equally expected to help eachother out no matter what. Mary never refers to her staff as individuals who work for her, instead she says they work with her. The core of the business is built on trust and reciprocity, one of the two most important features of a successful business (Silverman 2015, TED.) Generally speaking, not only the clientele but also the staff has benefited greatly from this. Blurred lines of leadership have advantages, but the costs may include staff getting too comfortable in situations that sabotage their performance.

At the head of our operational on-the-floor team is Chef. Chef has worked for Mary for over five years which has contributed to a close relationship unlike other ‘bosses’ to their employees. Chef is expected to set an example and lead the team to perform at their best. Chef's personality, in combination with her close relationship with Mary, makes it hard for her to define her position successfully. At her core she is very social and casual, two great qualities in an individual but qualities that, in my opinion and observation, may serve as a disadvantage while at work. Chef brings her personal life to work, she is hesitant with confrontation, and oftentimes takes shortcuts. She repeatedly chooses shortcuts even though Mary has made it clear they are not allowed. One specific example that went on for weeks was that she would “86” items (meaning they were unavailable) when we actually did have them. I believe the reason she 86’d the items was because she just did not want to take the time to prep them, or did not want to walk to storage to get them. It was easier for her to just say that they were out of stock. It was unthinkable for me to question her since we all place our trust in her as head of the restaurant and follow her lead. The other cooks soon picked up on this habit and began to make these decisions themselves even when she was not there. Two individuals took it further and started making decisions that resulted in being reprimanded, suspended, and one of them even lost his job. They closed the kitchen early on several occasions, gave discounts when they shouldn't have, and took food without paying for it. This resulted in below standard service as a restaurant as a whole, and in general not meeting any standards of what our jobs entailed. Another incident of Chef’s role as a leader who does not set good examples is when I saw her playing video games on her phone when she was supposed to be placing orders for the restaurant and checking on her team. Despite Mary’s efforts at accommodating staff and reciprocating their contributions, many still take advantage of this, which brings up a question of character as an employee. Without mutual exchanges, people’s motivation is driven by their desire to get more for what they give (Hasty 2023, 7.6), and this results in greedy individuals whose only interest is themselves rather than a common and social well-being. From my observations, there are plenty of mutual exchanges in the restaurant. Many employees, especially the individuals used as examples, have been awarded raises and given accommodating schedules in hopes of motivating them to perform at a standard level and meet expectations.

Gender roles could also be a factor here because employees might be less likely to respect and or follow rules that their boss implements because she is a woman, stemming from gender inequality. “Interpersonal inequalities, which are power imbalances that are rooted in personal biases, occur every day, reifying and naturalizing inequalities that exist at institutional and systemic levels” (Hasty 2023, 9.1). I did not witness anything that can confirm this assumption but it is something I have questioned before. Interestingly enough, we have developed a leadership team of all women. Starting with the restaurant being woman owned, the head chefs are both women, the general manager is a woman, our head lead at the bistro is a woman along with our head lead at the bakery too. All but one of five assistant leads are also women.

The work ethic of the customer service industry includes expectations of being welcoming, friendly, and efficient. Mary emphasizes these expectations and establishes that at Lola’s Bistro and Bakery our guests are always the priority during service hours. Mary’s work ethic differs from many of my coworkers. She gives it her all and puts in long hours to achieve her goals. Some of my coworkers come in and are satisfied with doing the bare minimum or less. Outside of the self-interested behaviors that have developed with many employees, there are also the positives. I have noticed my behaviors, which Mary has commented on being positive, have been mirrored by coworkers. Likewise, I follow my teammates whose work ethic I admire, those who function with the sense of urgency I think we all should have. These are the kinds of inconsistencies in work ethic found in family owned businesses.

Hasty, Jennifer, David G. Lewis, and Marjorie M. Snipes. 2022. Introduction to Anthropology.

Harris, Marvin, and Orna Johnson. 2007. Cultural Anthropology. 7th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

Shigihara, Amanda Michiko. 2014. A “professional back place”: An ethnography of restaurant workers. PhD diss. University of Colorado at Boulder.

Silverman, Aaron. 2019. “How I built the number one new restaurant in America.” TED.

My name is Tamia Manosalvas Cordova. I am a student at San Diego City College and have been taking classes here since the fall of 2019. I am a Communications major and a future educational goal of mine is to transfer to a 4-year University to get my degree. I am fascinated by language and hope to learn more languages throughout my life. With language comes different cultures which is also something I am extremely drawn to. I work best in group settings and in open discussions, I love working with people and talking, which is why I chose to study Communications.

Obesity, a condition characterized by excessive body fat accumulation, has reached epidemic proportions worldwide, affecting millions of people. While environmental factors such as diet and physical activity undoubtedly play a significant role in obesity, there is increasing evidence suggesting that genetics also contribute to this multifaceted condition. If culture and genetics play a part in obesity, how much, and what could this mean for the future of medicine? In this article, I will closely examine the relationship between genetics and obesity, drawing insights from three articles: "Genetics and Obesity" by Ekta Tirthani et. al (2021), "Twin Studies in Finland" by Jaakko Kaprio (2012), and "The Genetics of Obesity" by Blanca M. Herrera and Cecilia M. Lindgren (2010). We now understand and can isolate predetermined genetic variants associated with obesity. With CRISPR-Cas9 technologies we may be able to suppress obesity in predisposed individuals through new medicine.

The background section of the articles provides a comprehensive overview of the current understanding of the genetics of obesity. Tirthani (2021) emphasizes how recent advancements in genetic research, such as the discovery of genes responsible for monogenic forms of obesity, have shed light on the complexity of genetic factors involved in obesity. Kaprio (2012) cites the increasing prevalence of obesity and its potential familial aggregation as key motivations for investigating the heritability of obesity. Herrera and Lindgren (2010) discuss the possible genetic variants associated with obesity, emphasizing the significance of the FTO gene in influencing body weight.

Their methods range from looking at entire populations to gene variants. Tirthani (2021) used a combination of in vitro cell culture experiments and animal models to elucidate the mechanisms by which genetic variants influence obesity. They highlight how the discovery of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology has enabled researchers to determine the significance of specific genetic variants in regulating body weight. Kaprio's (2012) research involves twin studies, utilizing the unique genetic similarity between monozygotic and dizygotic twins to estimate the heritability of obesity. Herrera and Lindgren (2010) primarily conduct genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to identify genetic variants associated with obesity in large populations.

The authors present compelling data that supports the hypothesis that genetics contribute to obesity. Tirthani (2021) demonstrates how the knockout of certain genes involved in appetite regulation leads to obesity in animal models. Kaprio's (2012) twin studies reveal a significantly higher concordance for obesity in monozygotic twins compared to dizygotic twins, suggesting a strong genetic component. Herrera and Lindgren (2010) identify several genetic variants, including the (fat mass and obesity associated) FTO gene, that are robustly associated with obesity.

Tirthani (2021), concludes that genetic factors are indeed pivotal contributors to obesity, highlighting the crucial role of genes involved in appetite regulation and energy balance. Kaprio's (2012) findings suggest that genetic influences account for approximately 40-70% of the variation in body mass index (BMI) and obesity, reinforcing the importance of genetics in obesity etiology. Herrera and Lindgren (2010) emphasize the need for further research to decipher the biological mechanisms underlying the genetic variants associated with obesity. Schoenberg (2023, 2.4.2.2) reinforces the importance of environmental factors. For instance, you may have the FTO gene and still maintain a low BMI for years. If you were to become inactive due to injury or illness you would suddenly be taking in more calories than your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) and accumulate more adipose tissue due to an environmental change. If you had the FTO gene, you would gain more.

These articles have far-reaching implications for medicine and the treatment of obesity. The identification of specific genetic variants involved in obesity opens up possibilities for precision medicine, where tailored treatments based on an individual's genetic makeup could be developed. Tirthani (2021), argues that the research on CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in the context of obesity holds promising prospects for future therapeutic interventions. They argue that a deeper understanding of the genetic determinants of obesity could potentially lead to personalized treatment strategies targeting specific genetic variants. Kaprio's (2012) twin studies highlight the potential for genetic counseling and early intervention in individuals with a strong genetic predisposition to obesity. Herrera and Lindgren (2010) underscore the importance of integrating genetic information into obesity prevention and treatment strategies, enabling personalized interventions based on an individual's genetic risk profile.

In conclusion, the articles "Genetics and Obesity" by Tirthani (2021), "Twin Studies in Finland" by Kaprio (2012), and "The Genetics of Obesity" by Herrera and Lindgren (2010) collectively emphasize the substantial impact of genetics on obesity. The interaction between genetic and environmental factors in the etiology of obesity underscores the complexity of this condition. These studies pave the way for further research into understanding the intricate genetic mechanisms that contribute to obesity, ultimately leading to improved prevention strategies, personalized treatments, and enhanced healthcare outcomes for individuals grappling with this pervasive health issue.

Herrera, Blanca M., and Cecilia M. Lindgren. "The genetics of obesity." Current diabetes reports 10 (2010): 498-505.

Kaprio, Jaakko. "Twin studies in Finland 2006." Twin research and human genetics 9, no. 6 (2006): 772-777.

Schoenberg, Arnie. Introduction to Physical Anthropology version: 10 July 2023 https://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/bio/intro/section2.html#cellular%20biology

Tirthani, Ekta, Mina S. Said, and Anis Rehman. Genetics and obesity. (2021).

Timothy Nelder, a graduate of Stow-Munroe Falls High School in Stow, Ohio, embarked on a career journey by enlisting in the Marine Corps as a diesel technician. During his service as a marine, Tim attended multiple schools and held various positions. However, it was his time at recruiting school that eventually led him to his current academic pursuit. For three years, Tim served as a recruiter in Detroit, Michigan, an experience that proved to be immensely challenging yet rewarding. Being part of the community and assisting young individuals in pursuing their aspirations brought him great joy. Tim excelled in his role, performing exceptionally well, and this fueled his desire to channel his passion into a related career path after medically retiring from service. Recognizing similarities between the real estate industry and his previous responsibilities, Tim made the decision to utilize his education benefits to acquire real estate licenses and pursue a degree in Business.

Comparing Gorillas and Humans through primate observation can provide valuable insights into the behavioral similarities and differences between these two species. About 8-9 million years ago, the descendants of the dryopithecines in Africa diverged into two lines--one that led to gorillas and another to humans (O’Neil 2012). By observing their behaviors, researchers can unravel evolutionary links and gain a deeper understanding of the complex social structures, communication patterns, and cognitive abilities that define and represent these two intelligent beings on a level that’s very familiar; this comparative approach helps shed light on the evolutionary processes that have shaped the behaviors of both species, offering valuable perspectives on the origins and development of human traits and social dynamics. Studying Gorillas and Humans side by side also highlights the unique aspects of each species' behavior and cognition. Humans possess advanced language skills, complex problem-solving abilities, and intricate cultural practices that set them apart from their Gorilla counterparts. By observing Gorilla behavior in their natural habitat and comparing it to human behavior, researchers can identify the distinctive features that make us truly human. This research fosters a deeper appreciation for the rich diversity of life and helps us better understand our place within the primate family tree while encouraging efforts to protect and conserve these remarkable beings and their habitats.

The observation of primates is a part of biological anthropology as primates are our closest living relatives. Biological Anthropology, also known as Physical Anthropology, is the study of human evolution and the variations of all humans. By analyzing and studying primates, we can find the similarities between our species and make new discoveries on how our ancient ancestors may have behaved and evolved into the modern humans of today (Schoenberg 2022).

For decades it’s been known that humans and gorillas have genetic similarities and now share a common ancestor, however distinguishing our behavioral similarities has been questioned. We wanted to truly find out if we can find similarities between humans and gorillas in terms of their behavior and physical traits at the San Diego Zoo.

The comparison of Gorillas and Humans through primate observation serves as a valuable endeavor rooted in respect for both species and a dedication to expanding our understanding of the natural world. This study is conducted with a commitment to ethical research practices that prioritize the well-being, dignity, and conservation of these intelligent beings. Our observations are carried out with a deep sense of responsibility toward the subjects involved. We recognize that Gorillas, as well as Humans, possess unique traits and qualities that deserve admiration and protection. Throughout our research, we ensure minimal intrusion into their natural behaviors and habitats, prioritizing non-disruptive observation methods.The knowledge acquired from this study is pursued with an intention to contribute positively to the fields of evolutionary biology, behavior, and conservation. By unveiling the shared and distinct characteristics of Gorillas and Humans, we seek to further conservation efforts and promote awareness about the significance of safeguarding their habitats and well-being. Our ethical compass guides us in fostering a culture of understanding and compassion. We acknowledge that the study of primates carries ethical responsibilities that extend beyond research. As stewards of this knowledge, we endeavor to communicate our findings accurately and responsibly, inspiring empathy and fostering informed decision-making among both the scientific community and the broader public.

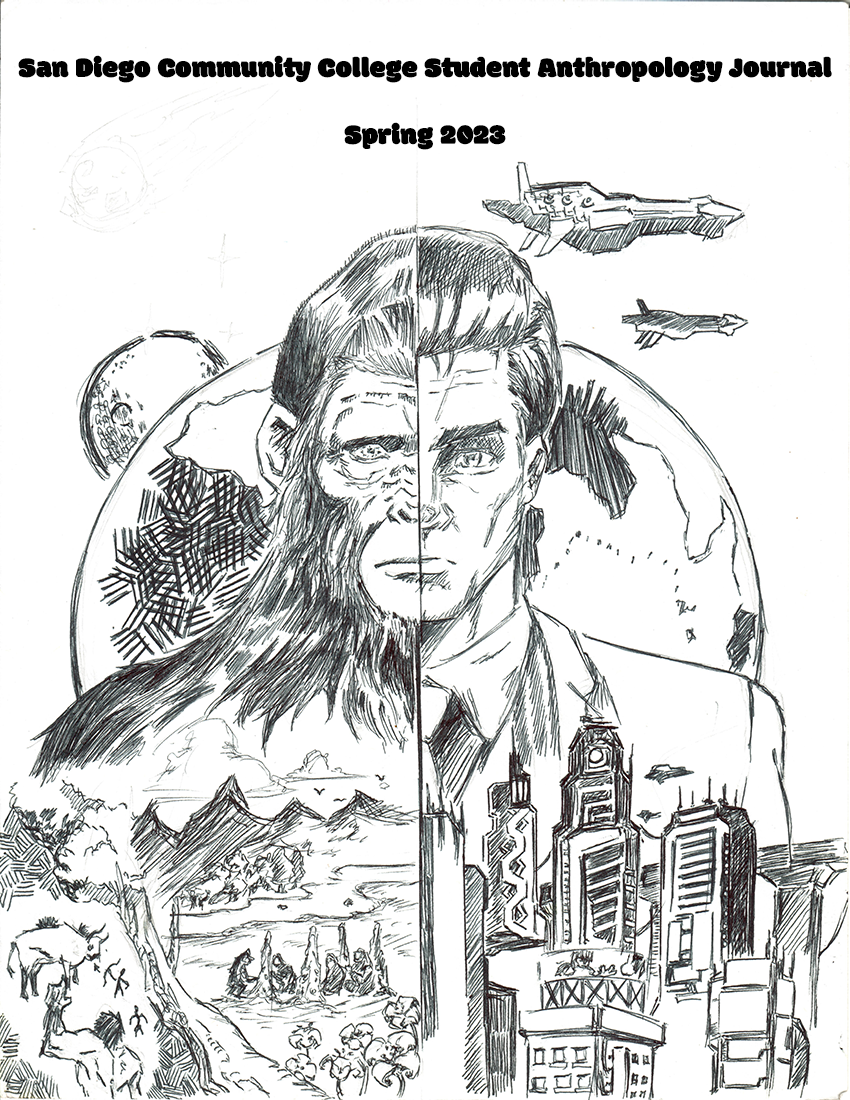

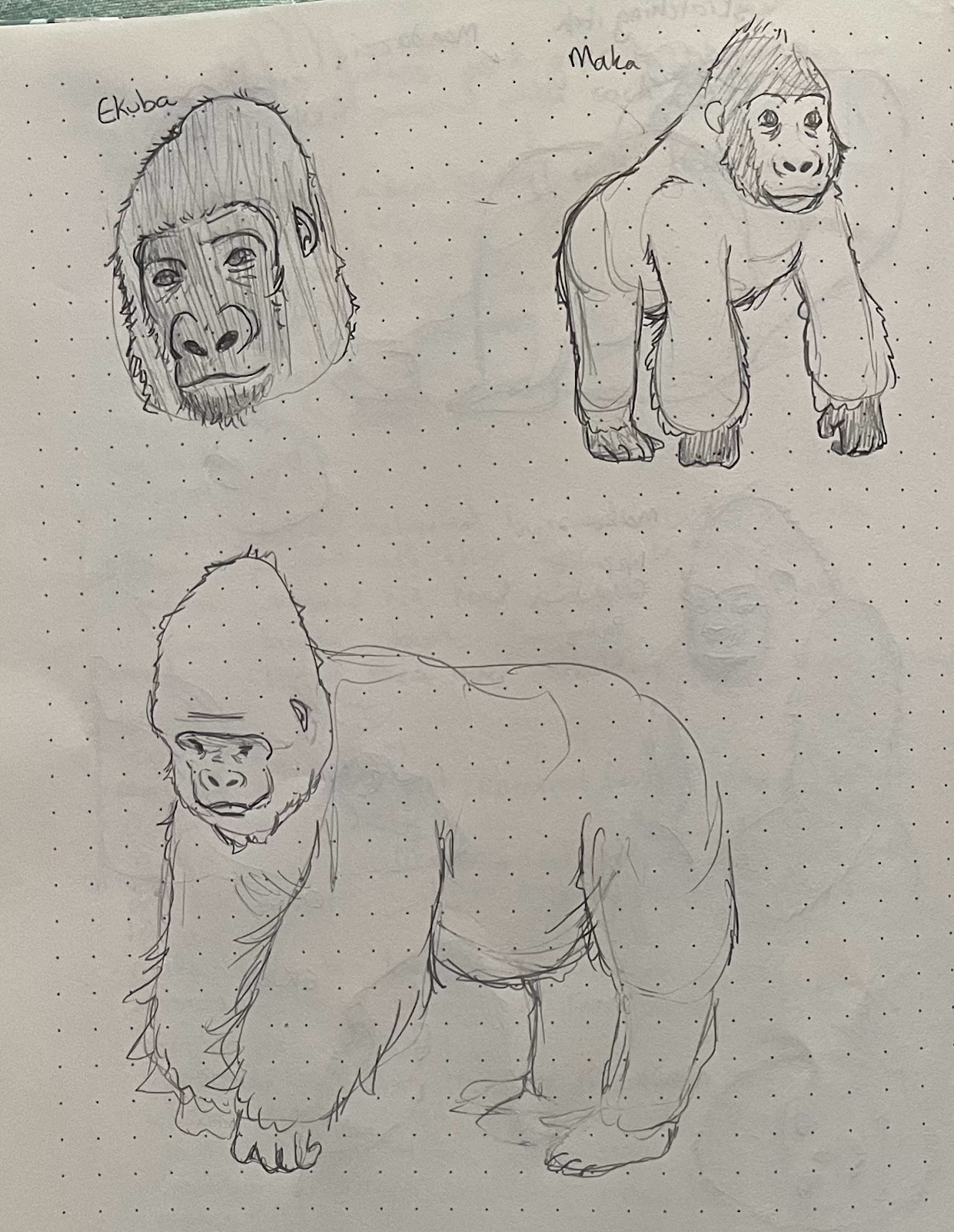

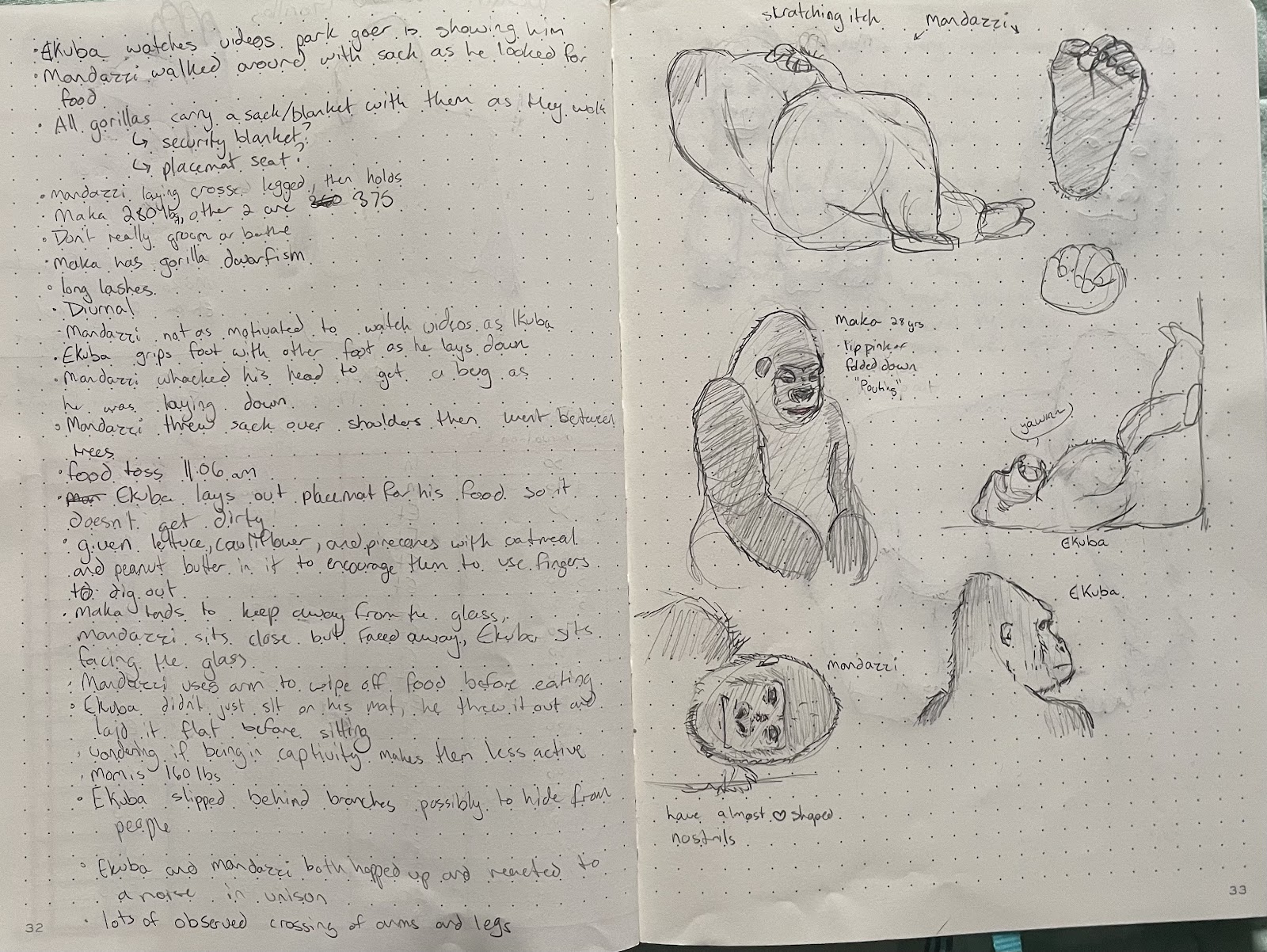

We read articles to gain more information about gorillas, about their physicality, behaviors, as well as some information about the evolutionary line connecting gorillas and humans. We went as a group to the San Diego Zoo on a Sunday and conducted observations between 11 am and 2 pm. Equipped with notebooks, we each created charts for timed focus observations of individuals within the pen, collaborating to put together ethograms for each observation. Each observation period was 10 minutes, broken up to mark a noted behavior every 30 seconds at the ring of a timer. We also spoke with the staff on hand to gather more information about the present gorillas, such as names, ages, and specific physical characteristics to tell them apart for a second ad libitum note taking observation. Darrian also made drawings (figure 2.)of the observed subjects and did a secondary observation day on Wednesday August 8 of two of the gorillas .

Below are the behaviors and codes used for the ethogram during observation:

Stick Use = St

Eating = Et

Display (chest beating, teeth bearing) = Ds

People Watching = Pw

Interacting with Others = Wo

Moving = Mv

Inactivity = In

Out of Sight = OOS

Inactivity was used to document when the subject was laying still or sitting without looking at the onlookers of the park.

We observed 6 western lowland Gorillas at the San Diego Zoo. The zoo staff splits the 6 gorillas into 2 separate naturalistic groups and releases them into the exhibit at different parts of the day. We watched them in 10 minute intervals over the course of 4.5 hours for a total of 116 observations, removing instances where the gorillas were out of sight. In the morning we observed a troop of 3 male gorillas named Maka, Mandazzi, and Ekuba (figure 1.).

Figure 1. Ekuba and Maka

Their behavior was relatively similar throughout the morning we watched them, spending most of their time either eating, staying sleepy and inactive after eating their meal, and their primary favorite activity–people watching. As lazy as the gorillas were that morning, it’s easy to compare them to ourselves, as if we were in our homes all day, every day. The behavior most exhibited was Inactivity. The gorillas would sit against the glass or lay with their backsides pressed to glass while faced away from the guests of the park without sleeping or moving for extended periods. The second most common behavior witnessed was eating. We were fortunate to be able to witness feedings of the gorillas, however it limited the amount of data we could collect on other behaviors.

Figure 2. ethogram

Towards the afternoon into the evening, they swapped in the second troop of gorillas, a family consisting of an older male gorilla named Paul, the female gorilla Jessica, and their 8 year old son, Denny. For a short time we got to watch Paul in particular, and he seemed especially hungry as all he did was eat the entire time, before going out of sight for quite a while. The outlier of the group was the youngest, Denny, who while feeding would move around the enclosure and played a few times with his food. We noticed that Ekuba was the gorilla who watched and interacted with the crowd the most. He would sit facing towards the glass watching people gathered around him, though reacting minimally. There was even an instance observed where a guest of the zoo came up and showed him an iPad playing videos of the gorillas enclosed and Ekuba would watch the video shown to him. On Wednesday, Ekuba again was observed watching the crowd that gathered and he pressed his face to the glass before baring his teeth, before he then laid down facing away from the glass again. This was the most extreme of the behaviors noted for all observation periods.

The physical attributes of gorillas and humans provide fascinating insights into the evolutionary paths these two species have taken. Here, we delve into the key differences and similarities in their physical characteristics.

Gorillas possess a robust skeletal structure optimized for their quadrupedal locomotion in forested environments (Thorpe 2007). The elongated arms and relatively short legs of gorillas are adaptations that aid in efficient movement through the dense vegetation of their habitats. Their shoulder blades are positioned to accommodate the demands of knuckle-walking, where they support the weight of the gorilla's body as it moves on all fours. In contrast, humans have evolved to be bipedal, with an upright posture and a distinct arrangement of the skeletal system. The shape of the human pelvis, spine curvature, and arrangement of lower limb bones enable efficient walking and running on two legs (Cunningham 2010).

Figure 3. ad libitum observations

Gorillas are renowned for their remarkable physical strength, particularly in males who develop large muscles, especially in the upper body. The silverback gorilla showcases significant muscle mass and power, which plays a role in asserting dominance and maintaining group cohesion (Briggs 2021). Human muscle structure differs from that of gorillas due to our bipedal nature. While gorillas rely heavily on upper body strength for activities like climbing and knuckle-walking, humans have developed lower limb musculature that facilitates sustained endurance activities such as long-distance walking and running. Gorillas have longer arms relative to their legs, whereas humans possess longer legs in comparison to their arms. These differences reflect the adaptations required for their distinct modes of movement (Choe 2018).

In conclusion, the comparison of Gorillas and Humans through primate observation holds significant importance in advancing our knowledge of both species and the broader field of evolutionary biology. By studying these remarkable creatures' side by side, we gain invaluable insights into our shared past and the intricate web of life that connects us. Understanding the behavioral and physical similarities and differences between Gorillas and Humans not only deepens our comprehension of our own origins but also contributes to conservation efforts and ethical considerations for these endangered animals. Moreover, such research gives us a sense of humility and wonder, reminding us of the remarkable diversity of life on our planet and the urgent need to protect and preserve it. By continuing to explore and appreciate the unique characteristics of both Gorillas and Humans, we embark on a journey of self-discovery and ecological responsibility, fostering a harmonious coexistence with our primate cousins and the natural world.

Thorpe, Susannah K. S., Roger Holder, and Robin H. Crompton. “Origin of Human Bipedalism As an Adaptation for Locomotion on Flexible Branches.” Science 316, no. 5829 (June 1, 2007): 1328–31. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1140799. Cunningham, Christopher B.,

Nadja Schilling, C. Anders, and David R. Carrier. “The Influence of Foot Posture on the Cost of Transport in Humans.” The Journal of Experimental Biology 213, no. 5 (March 1, 2010): 790–97. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.038984.

Helen Briggs, BBC News. 2021. “Secrets of Gorilla Communication Laid Bare,” April 8, 2021, sec. Science & Environment. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-56676124.

Hashmi, Anita, and Matthew Sullivan. 2020. “The Visitor Effect in Zoo-Housed Apes: The Variable Effect on Behaviour of Visitor Number and Noise”. Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research 8 (4):268-82. https://doi.org/10.19227/jzar.v8i4.523. Langergraber, Kevin E., Kay Prüfer, Carolyn Rowney, Christophe Boesch, Catherine Crockford, Katie Fawcett, Eiji Inoue et al. "Generation times in wild chimpanzees and gorillas suggest earlier divergence times in great ape and human evolution." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, no. 39 (2012)

O’Neil, Dennis. 2012. “The First Primates” https://www.palomar.edu/anthro/earlyprimates/early_2.htm

Schoenberg, Arnie. “5 Primatology” Introduction to Physical Anthropology https://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/bio/intro/section5.html#primatology October 2021

My name is Kiran McKee, I’m the 5th generation in a long lineage of Veterans within my family looking to make use of my GI Bill and carve out a future career path that I would find genuinely rewarding and fulfilling. I’m personally interested and intrigued about the topics of evolution and our origins as a species and look forward to learning more as I’ll develop a better understanding of the world around me. And while my current passions may not be grounded in very scientific fields, I still have an interest in human and technological development as well and can’t wait to work on more of these projects!

My name is Darrian Major (she/they). I was born and raised in San Diego, raised by my grandparents who are both from Baton Rouge, Louisiana and very proudly Cajun. My grandmother's background is in nursing and mental health care while my grandfather was an engineer who assisted in the creation of the modern day GPS, so they both are from fairly intense careers that I had no interest in most of my life. Since highschool, I have previously been only a visual arts major- Painting, Drawing, and Photography specifically. I spent 7-10 years with that as my main focus before stepping away from academics when I was 18 to focus on working a variety of full-time jobs. As I approached age 28, I decided it was about time to possibly try attending school again, although deciding what I wanted to pursue was extremely difficult. I have personal interest in many fields from the arts to different sciences. It was only as the end of the 2022 year approached that I decided to try majoring in anthropology. I have always been fascinated by people and the history of the world as a whole, so I believed digging deeper into the field would be perfect for me. As much as my grandparents who raised me wanted me to dip into both of their respective fields, I get squeamish around blood and I'm bad at math. It did not seem likely for me- Whereas all the possibilities with anthropology fascinates me and there are unlimited possibilities of what can be learned from the world around us presently as well as the world past. My anthropology journey only recently began beginning 2023, so I am still learning and figuring it all out. I have taken Cultural Anthropology, Archaeology, and Biological Anthropology classes thus far.

Hello I'm Ryan Kestler, aged 30, and a former Navy veteran. I've been happily married for 11 years and am a proud father of two wonderful children. During my time in the Navy, I had the incredible opportunity to work on the flight decks of both the USS Boxer and USS Nimitz. This experience not only enriched my life but also took me to countries I had never imagined visiting. I'm currently embarking on my second year of college and just began my first Anthropology class. My aspiration is to major in Anthropology, with a specific focus on becoming an Archaeologist. Although I was born in Bad Kreuznach, Germany, I've called various places home, including South Carolina, North Carolina, California, and Washington State. At present, I lead a full-time RV lifestyle, allowing me to combine my love for travel with my pursuit of education. Immersing myself in nature is a passion of mine, and I indulge in activities like disc golf and hiking whenever I can. My ultimate goal is to attain a degree in Anthropology and secure a position in South or Central America, though I'm open to opportunities anywhere in the world. The prospect of contributing to archaeological endeavors and exploring new cultures fills me with excitement and purpose.

Primate self-medication, characterized by the ability to use specific herbs and non-food substances to alleviate discomfort caused by ailments, is a remarkable demonstration of their adaptability and survival skills that have been honed through natural selection. Humans, like primates, possess similar learning systems and patterns, acquiring knowledge about the medicinal properties of substances through observations and teachings from parents, neighbors, and doctors. This exchange of knowledge provides insights into the field of zoopharmacognosy, which studies self-medication behaviors in various animals (Domínguez-Martín et al. 2020, 1). The study of primate self-medication offers valuable contributions to fields such as cultural anthropology and physical anthropology. By analyzing articles and comparing data from the field, researchers can explore the connections between human and primate medicine. Furthermore, human advancements in medical developments have been facilitated by studying the effects of medication on primates, particularly chimpanzees (Downum 1993). Self-medication behaviors in primates, driven by the desire to alleviate unpleasant sensations, demonstrate their ability to recognize specific ailments and utilize different substances to address them. Primates, such as chimpanzees, exhibit changes in behavior that indicate the presence of parasites, itchiness, or diarrhea, prompting them to seek out and consume specific herbal medicines separate from their regular diet (Huffman 1997, 178).

Learning from previous generations is a crucial aspect of primate self-medication. Parents pass on knowledge about medicinal herbs and their seasonal use to their offspring. Similar patterns can be observed in other species, where adults warn younger members about toxic substances or dangerous objects (Rapaport & Brown 2008, 193). The transmission of knowledge through generations reinforces the idea that primates possess a deep understanding of medicinal practices. Studies examining primate behaviors have identified instances where primates rub substances into their fur or selectively consume minerals that are not part of their regular diet but serve medicinal purposes. Observations of feces have shown the presence of herbal remnants, further indicating the intentional consumption of medicinal herbs by primates (Huffman 1997, 178; Baker 1996, 264). Moreover, the study of primate self-medication offers insights into the interconnectedness of humans and primates. Human interactions with primates and their environments have led to advancements in medical developments. Likewise, the observation and study of primate medicines provide potential benefits to pharmacological studies and human medicine.

In conclusion, the phenomenon of self-medication in primates highlights their remarkable capacity for natural healing and adaptation. The exchange of knowledge between humans and primates mutually benefits both species and has the potential to revolutionize pharmacology and human medicine. By uncovering hidden medicinal properties and continuing research in the field, we can enhance medical outcomes for both humans and primates.

Baker, Mary “Fur rubbing: Use of medicinal plants by capuchin monkeys (Cebus capucinus)”, https://www.primatesmesoamerica.org/costarica/proyectos/Baker%20M.%201996.%20Fur%20rubbing%20use%20of%20medicinal%20plants%20by%20Cebus%20capucinus.pdf. 263-270 (1996).

Domínguez-Martín EM, Tavares J, Rijo P, Díaz-Lanza AM. Zoopharmacology: A Way to Discover New Cancer Treatments. Biomolecules. 2020 May 26;10(6):817. doi: 10.3390/biom10060817. PMID: 32466543; PMCID: PMC7356688.

Downum, Kelsey R., John T. Romeo, and Helen A. Stafford, eds. Phytochemical potential of tropical plants. Vol. 27. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

Huffman, Michael A. "Current evidence for self‐medication in primates: A multidisciplinary perspective." American Journal of Physical Anthropology 104, no. S25 (1997): 171-200.

Huffman, Michael A. “Self-Medicative Behavior in the African Great Apes: An Evolutionary Perspective into the Origins of Human Traditional Medicine: In Addition to Giving Us a Deeper Understanding of Our Closest Living Relatives, the Study of Great Ape Self-Medication Provides a Window into the Origins of Herbal Medicine Use by Humans and Promises to Provide New Insights into Ways of Treating Parasite Infections and Other Serious Diseases.” OUP Academic, August 1, 2001. https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/51/8/651/220603?login=false.

Rapaport, Lissa G., and Gillian R. Brown. “Social influences on foraging behavior in young nonhuman primates: learning what, where, and how to eat.” Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews: Issues, News, and Reviews 17, no. 4 (2008): 189-201.

Schoenberg, Arnie. Introduction to Physical Anthropology. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/bio/intro/section5.html#theory%20of%20mind.

My name is Carlyne Ada and I'm currently a sophomore at San Diego Mesa College, where I'm majoring in Computer Science. I've completed two semesters of Java and I'm really excited to learn more about technology and its various languages. I come from a mixed heritage, with a Filipino and Chamorro background. Growing up in a U.S. Territory was quite different from San Diego, where I'm now based for college. I'm still adjusting to the fast-paced lifestyle of the city, but I'm really enjoying it so far. Unfortunately, I grew up in an abusive household, so it was really important for me to leave that environment and start a new life. Since then, I've noticed a significant improvement in my behavior and overall well-being. Despite being a top student, I never really studied as much as I should have so that plummeted my grades in my freshman year as I did not have that push from my parents. But now that I'm more independent, I'm learning how to be more conscious of my learning style and how to study more effectively to boost my grades and overall understanding of different concepts. My ultimate goal is to pursue a career in technology, which I believe will provide me with stability and a better future for myself and my future family. I'm determined to continue my education and build a successful career, so I can enjoy a stable and fulfilling life.

My name is Yumi Hardy. I am originally from Japan and I was a dental hygienist. I came to the United States for church volunteer work for the first time. I got a scholarship for college and got married so I had to stop going. It was a very abusive marriage and I made money to put into my husband's college funds. I supported him for 4 years but after his graduation, he didn't give me a chance to go back to college. After he graduated, he became an FBI agent and pulled a gun on me. The abuse was too much and I had to run away from home with my 5-year-old son so we became homeless. A lot of Americans don't know there are international laws for American kids. I couldn't go back to my home country, Japan, because I will be a criminal for kidnapping my own child. Because of this, I established my own massage business and taught holistic care. I traveled around the world and have been a massage therapist for 20 years. When I see my massage patients, I really want to heal them with a more holistic approach including massage, herbal medicines, meditations, counseling, hydrotherapy, energy healing etc. There are tons of medications everywhere and I decided I will be a naturopathic doctor. I have been coming back to Mesa College since 2018. Believe it or not, a homeless single mom will be a doctor in the future. It is very challenging working and going to school on top of being a mom. I don't want to become a Chinese medicine doctor or acupuncture doctor. They only make 80K a year while naturopathic doctors make 200K a year. It also takes a long process(10-12 years) to be a doctor. When I finish my 2 more years of pre-med(Biology, chemistry, organic chemistry, math, physics, and 1 more GE) I will transfer to UCSD. My major will be Biological anthropology. This is why I am taking these courses right now. I will go to a Naturopathic medicine doctor's program for 6 more years. When I get my doctor's license, I want to open medical clinics in California & Japan. I have been creating my community already before going back to Mesa, so I have patients already. I have more business plans already as I have been to 38 countries and I am going to use my network for bringing doctors and researchers to the U.S. and Japan. I will be a seminar provider and I am also going to teach online. 3000 students with $30-50 a month for tuition, will come as I used to do before Covid19. Most people don't know how to do business however, I know how to do it already. I love running a business so I can travel the world and work more too. More studies will mean I will be able to save more lives. I read a lot of people's reasons but they don’t tell how they are helping others or how they do it or their ideas. I want to share mine. I have been giving FREE massages to doctors at my massage office because I can't go to Ukraine to save people. However, if I care for doctors here, maybe this spirit will reach Ukraine. This Christmas, I am going to go to the 39th country, Egypt and stop by Italy. I have been to Italy more than 20 times. I am so excited to see bones in Egypt too. I took an ethnic costume class from Mesa College a few years ago and it also taught me something similar to anthropology. I had a hard life but I still love people and I would love to connect with people more.

My name is Areli Sandoval. I spent most of my childhood growing up in Tennessee Joe in a very hectic and packed household. Growing up in that space led me to art in almost any form. If you had asked me what I was doing in middle school as a hobby, I would've said reading, writing, painting, and drawing-just about anything that could be considered artistic. Throughout middle school and high school, I never knew what I wanted to do for a living. I had ideas, maybe being a writer, although the option of being a teacher would've also been an amazing opportunity. Maybe being a small business owner would've also suited me. However, a month before graduating high school, my dad told me about one of his coworkers who was leaving to continue his side job as a graphic designer. At the time, I had an internship making and designing merchandise, marketing, and selling it. After many appointments with my counselor, we found out that the best path for me to become a graphic designer would be to declare myself as a fine arts major, graduate with my associate's degree, and transfer to a four-year university with an emphasis on graphic arts.

Anthropology is the study of humans and our relatives, other hominids. It studies how humans are shaped by the environment, and how the environment shapes us. It is not surprising that we have a large influence on the environment, as humans changed from being shaped by the environments (evolution/natural selection) to being the ones to shape how we live. Yet, this does not change the lasting impact that nature has on humans and other hominids. Biological anthropology explores changes in hominid biology.

One constant throughout human evolution, apart from the need for rest and energy intake, is our need to defend ourselves from microscopic pathogens. Humans are a warm, nutrient-rich resource that otherwise would be attacked by many microorganisms in the world. I research here a few papers on the immunology and evolution of humans (Homo sapiens) and other hominids. I will focus on the book Immunity, the Evolution of an Idea by Alfred I. Tauber (2017); it deals with what we know about human and hominid immunity, as well as touching on the history of discoveries. In conjunction with Tauber, I will reference two other articles, “Evolution and Immunity” by Jim Kauffman (2010), and “Impact of Historic Migrations and Evolutionary Processes on Human Immunity” by Jorge Dominguez-Andres (2019).

This research is particularly pertinent right after the devastating COVID-19 pandemic changed the world. The prospect of disease has haunted human populations since the beginning of time, from the devastation of Athens (Littman 2009), to how the bubonic plague shaped the modern world. By learning how humans and other animals have evolved and changed over time to strengthen their innate defenses, it could help humans rely less on antibiotics. Overusing antibiotics has been linked to the creation of “superbugs”, antibiotics-resistant pathogens that are much more dangerous for susceptible populations (Llor 2014).

The book Immunity, the Evolution of an Idea sets out with a very intriguing question: how much does the immune system shape the identities of the individuals? If an individual could be shaped by their own immune system, the same could be said about a species. Humans have evolved much since the earliest known fossil of hominid species, with multiple morphological changes to bones and muscle structures (Schoenberg 2021). The same thing can be seen in the immune system. On a broad scale, the development of a species can be measured by sophistication of their immune system. In this way, species can be put into three different categories depending on how they deal with pathogens: 1) innate adaptive immunity, 2) lymphocytes, and 3) antigen receptors.

Contrary to previous assertions, researchers have found that insects and vertebrates do have an adaptive immune system (Kauffman 2010). This evolved into more sophisticated means of defense, like lymphocytes, which can be seen in jawed fish, which create lymphocytes, like T cells and B cells. With both innate immunity and lymphocytes, the immune system is resilient enough to stop most pathogens, but it is still scattershot. The main ways these organisms destroy the pathogens are to create enough lymphocytes to absorb the pathogens, but it is almost impossible for the individual to get adaptive immunity, which means it is liable to be reinfected by the same pathogens multiple times, weakening its ability to survive long term, because fighting off infections is very energy consuming. The evolution of antigen receptors for specific antigens allowed individuals, and the species, to more efficiently adapt to diverse infections and diseases.

Entire branches of the animal kingdom can be defined by the presence or lack thereof of a certain immunity system, but within a single species, including humans, immune systems are shown to be much different based on geographic location. Each environment humans are part of promotes and discourages certain cultural practices and behaviors, and it also promotes certain biological traits in human populations as well, especially diseases (Kauffman 2010). Migration to different environments was the greatest evolutionary pressure on hominids (Dominguez-Andres 2019). The multiple geographic locations and isolation promoted specialization in the human immunity system. The selective pressure could create a “bottleneck” event where most of the survivors have the beneficial traits (Schoenberg 2021).

One example of this adaptation is the presence of malaria and sickle cell disease in Africa.

Populations remaining in sub-Saharan Africa have been exposed to malaria for such long periods of time that their genetic structures have been shaped by the severity of malaria (Plasmodium sp.) infections. In 1954, Allison described that sickle cell disease distribution was confined to Africa and was associated with the geographical presence of malaria. [...] This finding led to the more recent description of the existence of mutations in the Hemoglobin-B (HBB) gene as a result of natural selection driven by evolutionary pressure for protection against malaria [Dominguez-Andres, 2019]

Sickle cell disease happens in Africa because malaria is prevalent there, and the HBB gene is a net benefit against this very dangerous and infectious disease. It is a net benefit because the mutations that cause sickle cells and affect the hemoglobin’s shape and protect the cells from malaria.

Geographic location is not the only cause of specialization and differentiation of humans and other hominids. One other way it could appear is between human subspecies. An incredible possible discovery is the possibility that Neanderthals are immune, or at least resistant to, HIV-1 through the TLR-10 expression (Dominguez-Andres 2019). This expression is also linked to increases in immune response speed to other pathogens and diseases as well. These differences can be seen in Neanderthals who have migrated from Africa. Not having to worry about malaria pathogens makes HIV one of the biggest threats to the neanderthal populations, and the more diverse amount of pathogens would selectively pressure more proactive responses to more diseases.

The change in Geography can be seen even in modern humans. For example, Africans and people with African origin tend to have greater inflammation and cytokine reactions to diseases. This advantage is a net positive, yet the more robust and more extreme reactions to pathogens could also cause higher rates of autoimmune disease (Dominguez-Andres 2019). This shows how most mutations come with drawbacks, which the advantages and disadvantages are completely relative to the location and the environment.

This research focused on changes in immune systems, and the way the immune systems and the systems of self defense that human and hominid evolution has created to help us survive. This could prove to be useful in pharmaceutical and medical fields, with breakthroughs in gene therapy and genetic modifications. It could prove necessary to protect the public against new and deadlier pathogens in the future.

Dominguez-Andres, Jorge. “Impact of Historic Migrations and Evolutionary Processes on Humans” Trends in Immunology, 27 Nov. 2019. https://www.cell.com/trends/immunology/fulltext/S1471-4906(19)30210-8

Kauffman, Jim. "Evolution and Immunity." National Library of Medicine, 1 Aug. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2913256/. Accessed 3 Aug. 2023.

Littman, Robert J. "The Plague of Athens: Epidemiology and Paleopathology." National Library of Medicine, 1 Jan. 2009, DOI: 10.1002/msj.20137 Accessed 4 Aug. 2023.

Llor, Carl, and Lars Bjerrum. "Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem." Therapeutic advances in drug safety 5, no. 6 (2014): 229-241.

Schoenberg, Arnie. Introduction to Physical Anthropology. 10 Oct. 2021. arnieschoenberg.com/anth/bio/intro/index.html. Accessed 3 Aug. 2023.

Tauber, Alfred I. Immunity: The Evolution of an Idea. Oxford University Press, 2017.

My name is Truc. This is my second year at college, and my aim for this year is to catch up. I arrived in the middle of COVID, and everything was in chaos, and I basically missed two years of school. I really want to excel at school, and not to lose any more progress. I want to focus on Computer Science. I have two siblings, and I want to make sure they can be proud of me when they grow up.

Humans stand out among Earth’s life. Our profound impact on the planet is incomparable to any other species alive today. There was however, an event in the distant past to which we can draw parallels and perhaps can help the way we think about the crisis we face. During the “Great Oxygenation Event” (GOE) around 2.4 billion years ago, cyanobacteria caused a dramatic increase in oxygen in the atmosphere (Schirrmeister et al. 2015, 769). Humans, then, are not the first to cause a climate change. This study will compare literature on the evolution of cyanobacteria and the GOE, with the evolution of humans and modern climate change to identify similarities and differences between these events. As modern climate change is an ongoing event, the end results can not be compared. The GOE resulted in likely “the greatest of all mass extinctions on planet Earth” (Dorado et al. 2010, 53). Humans shall determine whether our event ends similarly or differently.

Cyanobacteria are among the oldest forms of life on Earth, and their origins possibly date back over 3 billion years ago. They can be characterized by photosynthesis, and in fact “cyanobacteria are the only organisms in which oxygenic photosynthesis has evolved” (Schirrmeister et al. 2015, 769). All other life that photosynthesizes, such as plants, only do so through a symbiotic relationship with cyanobacteria (Sagan 1967, 225). In the time leading up to the GOE, cyanobacteria flourished. “The autotrophic lifestyle of cyanobacteria enabled them to conquer a variety of habitats including marine, limnic and soil environments, ranging over a wide scale of temperatures, from arctic regions to hot springs” (Schirrmeister et al. 2015, 769). Autotrophic refers to the “diet” of the cyanobacteria, and means that they sustain themselves on inorganic material. Photosynthesis may not have been the only key to their success. Genetic evidence suggests that multicellularity evolved in cyanobacteria around the time of the GOE (Schirrmeister et al. 2015, 769). Between photosynthesis and multicellularity, cyanobacteria were able to dominate their environment to such an extent that the oxygen they produced made a significant change to Earth’s atmosphere (Schirrmeister et al. 2015).

The evolution of humans is the focus of biological anthropology. In order to examine what separates us from the rest of animals, as well as what could have led us to impacting our climate, we shall focus on the hominins. The hominin branch comprises bipedal apes, of which Homo sapiens is the only extant species (Schoenberg 2022, 6). In other words, this is the human branch. The fossils of hominins show two significant trends: bipedalism–the defining trait of hominins–and encephalization, meaning the increase in brain size (Schoenberg 2022, 6.1).

Bipedalism was the first of these changes, and provided a number of benefits to hominins: including efficient long distance travel, increased visibility, and improved cooling (Schoenberg 2022, 6.1.1). The improved efficiency of bipedalism may have been crucial in enabling our next evolutionary trend, encephalization. A study of birds found that bigger brains are correlated with smaller pectoral muscles (Isler et al. 2006, 228). The pectoral muscles allow for more powerful but less efficient flight (Isler et al. 2006, 238). The implication is that the body must compensate for the energy costs of larger brains, and the authors make the connection to human evolution: “the trade-off between locomotor costs and brain mass in birds lets us conclude that an analogous effect could have played a role in the evolution of a larger brain in human evolution” (Isler et al. 2006, 228).

Encephalization may be the most significant evolution on the hominin branch. Encephalization is associated with more advanced tool creation and use, the development of language, and culture–the passing of learned information between generations (Schoenberg 2022, 6.1). As this evolutionary trend is occuring, hominins begin to emigrate out of Africa to occupy habitats around the world (Schoenberg 2022, 6.2.6). The trend of encephalization continued to the present, with the largest brains found in recent hominins such as Neandertals and Homo sapiens (Schoenberg 2022, 6.1.2). It is important to note that evolution is a slow process, and so we humans living today are “biologically the same'' as those that lived 100,000 years ago (Schoenberg 2022, 6.13.1). This means that the significant changes to human life that happened in recent history such as agriculture, civilization, and industry should be attributed directly to human culture, and only indirectly to encephalization.

In the 20th century, we noticed evidence that Earth’s climate is changing, and “the warming over the past century is unprecedented in the past 1000 years” (Crowley 2000, 276). It is now scientific consensus that this climate change is caused by human activity, with this stance exceeding “99% in the peer reviewed scientific literature” (Lynas et al. 2021, 1). A 2007 intergovernmental panel noted that “the observed widespread warming of the atmosphere and ocean, together with ice mass loss, support the conclusion that it is extremely unlikely that global climate change of the past fifty years can be explained without external forcing, and very likely that it is not due to known natural causes alone” (Alley et al. 2007, 10).

This changing climate poses significant threats to humanity. The negative impacts are too numerous to list, but those considered to be “very likely” include: increased incidence of death and serious illness in older age groups and urban poor, increased heat stress in livestock and wildlife, increased risk of damage to a number of crops, increased electric cooling demand and reduced energy supply reliability, extended range and activity of some pest and disease vectors, increased flood, landslide, avalanche, and mudslide damage, increased soil erosion, and increased pressure on government and private flood insurance systems, and disaster relief (Adger 2001, 4). This crisis will affect the world’s ecosystems as well: “we should expect both massive extinction and some evolution as variations in populations are selected for in the new ecological niches caused by extreme weather, drought, flooding, acidification of the oceans” (Schoenberg 2022, 8.1.3). In short, we are facing a disaster of our own making.

Our situation parallels in many ways that of the cyanobacteria 2.4 billion years ago. Photosynthesis and multicellularity in cyanobacteria can be considered analogous to bipedalism and encephalization in humans. Both humans and cyanobacteria evolved traits that allowed them to conquer habitats around the world. Both flourished to such an extent that they had a significant impact on their environment. Both caused an event that was harmful to themselves and caused mass extinctions. We can then consider the Great Oxygenation Event to be a cautionary tale for humans.

There is a key difference between the GOE and human-caused climate change. The GOE was caused by cyanobacteria evolution directly. Photosynthesis produces oxygen, so the oxygenation would have simply happened once the cyanobacteria were numerous enough to alter the atmosphere. Human climate change is associated with greenhouse gasses, primarily carbon dioxide (Crowley 2000, 276). The temperature and carbon dioxide levels of Earth’s atmosphere have stayed within a small, stable range for at least the past 1000 years (Crowley 2000, 272-275). Humans empires and nations covered the globe during that time. This means that climate change is not caused by simply the presence of humans, but rather the more recent greenhouse gas-producing activities after the industrial revolution. As previously mentioned, these behaviors are the result of human culture, as opposed to human biology.

This comparison offers us some insight and hope in facing the climate crisis. While cyanobacteria’s disaster was the result of their evolutionary path over hundreds of millions of years, we have created a crisis from rapid changes we have made in the past 200 years. The ability to make such significant changes in short periods of time suggests that we have the tools needed to alter our course to at least avoid worst-case climate change scenarios. It is important to acknowledge this hope if humans are to make actions to combat climate change, but it is equally important to note that while there is hope, the situation is dire. “Anthropogenic warming and sea level rise would continue for centuries due to the timescales associated with climate processes and feedbacks, even if greenhouse gas concentrations were to be stabilized” (Alley et al. 2007, 17). Climate change is already under way, so we must have a serious and determined approach if we are to limit the damage.

Humans are following a trail that was blazed 2.4 billion years ago by cyanobacteria. We are causing climate change that will result in human disasters and mass extinctions. We have the ability to make rapid changes to combat the crisis. Now each one of us will play a role in determining the outcome; whether we avoid disaster or prove to be no better than cyanobacteria.

Adger, Neil et al. "Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation And Vulnerability" Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change. (2001).

Alley, Richard et al. "Climate change 2007: The physical science basis." Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change. (2007).

Crowley, Thomas J. "Causes of climate change over the past 1000 years." Science 289, no. 5477 (2000): 270-277.

Dorado, Gabriel, Isabel Rey, T. E. Rosales, F. J. S. Sánchez-Cañete, F. Luque, I. Jiménez, A. Morales et al. "Biological mass extinctions on planet Earth." Archaeobios 4 (2010): 53-64.

Isler, Karin, and Carel van Schaik. "Costs of encephalization: the energy trade-off hypothesis tested on birds." Journal of Human Evolution 51, no. 3 (2006): 228-243.

Lynas, Mark, Benjamin Z. Houlton, and Simon Perry. "Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature." Environmental Research Letters 16, no. 11 (2021): 114005.

Sagan, Lynn. "On the origin of mitosing cells." Journal of theoretical biology 14, no. 3 (1967): 225-IN6.

Schirrmeister, Bettina E., Muriel Gugger, and Philip CJ Donoghue. "Cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event: evidence from genes and fossils." Palaeontology 58, no. 5 (2015): 769-785.

Schoenberg, Arnie. 2022. Introduction to Physical Anthropology. https://arnieschoenberg.com/anth/bio/intro/index.html

My name is Austin Gray and I am a physics student at Miramar and Mesa College. I am a thinker, and I like to spend my free time pondering the nature of our Universe. What will be its future? Are we alone, or are there others amongst the stars? What is the meaning of life? And what is the meaning of MY life? This is how I like to spend my free time! The question that really keeps me up at night however, is how will we deal with climate change? While I don't have all the answers (or any for that matter), who is to say what future generations might discover? It is this idea that has led me to believe I should use my life to help with solving the problems that threaten all of humanity. I would like to encourage others to consider just how important your life is- the future is in your hands!

Finding a cure for people who have AIDS may involve understanding their immune systems and how they fight off the disease. The immune system is determined by both the evolution of our own genetics, and some cures also include stopping the virus from multiplying and keeping up with the parasite’s evolution.