by Arnie Schoenberg

version: 1 September 2022

Figure 6.3 Early human handprint at * Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave about 30,000 years ago by Carole Fritz et Gilles Tosello, CNRS, Équipe Chauvet, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication ©2019

6.13 anatomically modern Homo sapiens

Anthropology asks the broad question: "Who are we?" Paleoanthropology asks a more specific question: "How did we get to be what we are?"

In this part of the class we go back in time to follow the branch of the tree of life that leads to us. In the previous sections, we compared and contrasted ourselves to other vertebrates, then to other mammals, then to primates, and mostly to hominoids (apes). In paleoanthropology we start from the split that separates apes from humans and continue on that branch, and all its side branches, until we get to us.

Paleoanthropology deals with hominins (also called hominids), or bipedal hominoids; apes that walk on two feet.

In previous sections, we compared ourselves to living creatures that you can see running around in their natural habitat, but in the paleoanthropology section, most of our knowledge is based on data gathered through archaeology, and we focus on hominin fossils, and how to interpret them.

The next few sections are going to bombard you

with specific dates, exotic places, hard to pronounce names, and plenty of

Latin. Please try not to miss the forest for the trees. We need to sweat the

details. The details are what paleoanthropologists use to support their very

tenuous hypotheses. But make sure that when you hear a specific factoid, that

you put it in context with a larger framework. So, if you hear "Toros-Menalla" you should think "that's kinda northwest of where most of

those other hominin fossils were found." If you hear a species called Homo ergaster you think "well it's later than the

australopithecines because it's of the genus Homo, but it's not quite us

because the species name is different than sapiens."

If you see a date for Lucy is 3.7-3.5 mya you think: "well she didn't use

stone tools because those only appear around two and a half million years

ago." If you read that Sahelanthropus tchadensis had a cranial capacity of 320-380 cc, you think

"before australopithecines hominins had about the

same size brain as chimps do now"

We have found hundreds of thousands of hominin fossils which represent tens of

thousands of individuals. When someone claims that there is no "missing

link" between apes and humans they are ignoring that huge body of evidence

gathered by thousands of scientists. The real debates are about how to include

those ten thousand individuals in our family tree, because these thousands of

fossils are just a tiny fraction of the billions of hominin ancestors that have

lived rich and important lives, but left no physical traces. A genealogical

analogy is that you may know from your last name that you belong to certain

clan, but you might not be able trace all your relatives back to that apical

ancestor; in paleoanthropology there are many gaps.

Try not to get lost in the details of paleoanthropology, and always bring it back to the context of time, place, and relation to the major trends. Important factors for fossils are: dates, where found, morphology (shape), and associated tools.

An excellent resource for this entire paleoanthropology section is Barbara Welker's 2017 The History of our Tribe: Homini

* articles on paleoanthropology are available from the journal PaleoAnthropology.

Footprints have become an icon of humanity, some left by an australopithecine around 3,500,000 years ago, which led to footprints on the moon.

Figure 6.1 * Laetoli footprints by Momotarou2012 (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Figure 6.2 lunar footprint NASA (public domain)

Feet are important, but another way to look at humanness, is the hand.

Figure 6.3 Early human handprint at * Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave about 30,000 years ago by Carole Fritz et Gilles Tosello, CNRS, Équipe Chauvet, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication ©2019

What makes us different from any other lifeform is this ability to leave our handprint. Of course, the two go together, because to make art with your hands, you first need to walk upright on two feet.

It's convenient for us to summarize the evolution of our species into a few broad trends that fit on the back of flash-cards: two feet, smaller teeth, big brains, culture, tools, language, large body size, wide geographic range... This is how evolution made us different from our closest living relatives: bonobos, chimpanzees, and gorillas.

But at the same time it's important to remember that evolution is not directional. Life doesn't progress towards an ultimate goal. There is no human essence that our species strives to become. This is more of that philosophical baggage we have leftover from Aristotle.

Scientists do use a creation metaphor, the concept of mosaic evolution, to describe how evolution creates a picture out of many different pieces.

Figure 6.4 Charles Darwin ©2009 Charis Tsevis, TIME Inc.

"Mosaic evolution" is a metaphor for how the picture of a living species can be seen as the evolution of many characteristics, or pieces of colored stones that work together to form a pattern, even though each of those pieces may have evolved at a different rate, and in our case, we can see a picture of modern human beings as a composite of many trends in hominin evolution. With locomotion we are concerned with the development of bipedalism. A fancy way to talk about an increase in brain size in the evolution of a clade (branch) is encephalization. The reduction of dentition is another trend. Toolmaking behavior is the only direct evidence we have for culture in early hominins. A good example of biocultural evolution are the trends in dentition and tool use: as we developed better tools, we no longer relied on our teeth to process food.

We are the only primate to walk on two feet. All primates can walk bipedally if carrying something or injured, but it's not their normal mode. This is a trend that goes back to primate evolution and our arboreal adaptation. Natural selection selected for being comfortable while vertical, both for vertical clinging and leapers with their torsos aligned with the vertical trunks of trees, and brachiators, where gravity pulls us into a vertical position as we swing from tree to tree.

There are several hypotheses for why evolution selected for bipedalism in basal hominins. Using two feet instead of four is more efficient for traveling long distances. Walking on two feet freed our hands for tools and communication. Walking tall meant we could see over the tall grass of the savanna to notice food and predators, and it could have help intimidate rivals or predators, and some claim that it would have helped us wade through shallow water. Getting up off the ground could have kept us cooler in the savanna heat, by moving our head farther away from the hot ground, and decreasing the amount of sun that hit our bodies when it was at its strongest. Anthropology's acceptance of multi-causal arguments means we don't have to choose one, and we can evaluate the likelihood and contributions of each hypothesis in different situations.

* Locomotor Energetics in Primates: Gait Mechanics and Their Relationship to the Energetics of Vertical and Horizontal Locomotion

* !Kung San persistence hunting suggests bipedal advantages:

cepha is Greek for head, encephalization is the head getting bigger, but we're really more concerned with the brain. Paleoanthropologists used to take skulls and fossil skull casts and pour rice into the foramen magnum until it was full, and then pour it out and you got the individual's cranial capacity. Now we use 3-D scanners instead of rice, but it's the same principle: how much brain did the individual have. It's usually measured in volume, like cubic centimeters, abbreviated as cc'. Both the absolute and the relative brain volume tends to grow as time goes on with hominin evolution, with a few exceptions. Neandertals actually had on average bigger brains than anatomically modern Homo sapiens.

Figure 6.5 the ratio of brain to body size by Peter Aldhous, Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0)

Besides having a bigger brain relative to our body size, the part of our brain dedicated to higher thinking is vastly bigger than any other animal.

.png)

Figure 6.6 Cerebral cortex neurons by Peter Aldhous, * "Does Brain Size Matter?" (CC BY 4.0)

Comparing the kind of brain may be even more significant than just comparing size or ratio, but when paleoanthropologists study encephalization in fossils, most of our data is limited to the size of the skull.* article on our scaled up primate brains

* article on the SRGAP2 gene associated with brain development and the origin of language

The classic theory is that bipedalism freed the hands from locomotion and allowed them to specialize in tool use, and this was supported by the correlation between complexity in stone tools and encephalization in hominins such as Homo habilis. Recent discoveries are pushing the dates of the first stone tools back before significant encephalization had occurred, but this is consistent with our observations of living primates. If we can see primates today make tools with a 400cc brain, we can imagine our ancestors doing the same with 450cc brain.

Figure 6.7 comparing finger bones by Tracy L. Kivell, from *"Early human ancestors used their hands like modern humans" ©2015

* Radio interview on the origin of the precision grip:

compare the tool sections of these pages: Oldowan to the Acheulian to the Mousterian to the Upper Paleolithic

* article that maps brain patterns to the hands and feet of primates suggests the dexterity required for tool used evolved before bipedalism

Figure 6.8 * flake attributes by Jos-Manuel Benito ēlvarez from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.5)

The evolution of the human capacity for language is tied to the development of encephalization and culture. You need a brain to process language, and language enables complex cultural transmission. Unfortunately, the evidence for the evolution of human language is scanty. The study of the evolution of human language was even banned by the French linguistic society in the 1800s.

* Approaches towards the origin of language

* article and video on an orangutan's capacity for producing human sounds

The evolution of hominin teeth is basically reduction, with a few counterexamples. Teeth are the hardest bone in the body, and so they tend to fossilize more than other bones.

skim the evolution of hominin dental morphology

Figure 6.9 "Puny Humans" by Abstruse Goose (CC BY-NC 3.0 US)

The methods of paleoanthropology are basically the same as paleontology: find a fossil or a gene, and then compare and contrast it to every other fossil, bone, or gene currently known. It is very detail oriented work on all fronts, with surprisingly few "aha!" moments, and many of the debates often come down to the interpretation of statistics.

Taphonomy comes from the Greek "taphos" or death, and it basically means the study of what happens to you after you die. The study of rotting and decay, and especially important for us, the study of how fossils are formed. This is a big problem because when we try to recreate an image of the past our data is sketchy. For example, we have a ton of pig fossils, and can talk in exhaustive detail about the evolution of pigs, but when it comes to human ancestors we have less to work with. We would love to find DNA from early hominins but the same capacity for unzipping for replication and protein synthesis makes it a fragile molecule that is unlikely to survive more than 100,000 years.

Remember that fossils are not bones, they are casts of bones. The general principle is that the older something is, the more difficult it is to date. Bones are living organs when they're in the body, and even after the individual dies, it takes a while for all the DNA and carbon to decompose. So with bones we can get accurate dates within hundreds or thousands of years. Fossils are the casts of bones; rock that has filled the space where a bone once was. Those are harder to date, and we usually use the geology where we found the bone, and dates are less accurate, +/- hundreds of thousands and millions of years.

Here is a metallurgy analogy. One of the oldest ways to make metal sculptures is called the lost wax method. You shape the object in flexible wax, then cover it with plaster to make a mold, then you pour molten metal into the mold and it melts the wax and takes the form of the mold. In fossilization, a bone gets buried, and the mud or ash solidifies around the bone to make a cast. Then acid in the groundwater slowly dissolves the bone, and harder minerals replace the more flexible hydroxyapatite, filling the mold and solidifying into the fossil.

READ DENNIS O'NEIL ON FOSSILS

Getting the dates right is crucial, but we hardly ever get an exact date, like something you could use for a time machine, usually it's just a statistical approximation. But, by combining multiple dating techniques our dates get more reliable, good enough to make conclusions about how to put fossils into groups of paleospecies.

READ DENNIS O'NEIL ON DATING OVERVIEW

READ DENNIS O'NEIL ON RELATIVE DATING

READ DENNIS O'NEIL ON CHRONOMETRIC DATING 1

READ DENNIS O'NEIL ON CHRONOMETRIC DATING 2

play around with this physics simulator of radioactive decay

* podcast on Cosmic rays date ancient human ancestor

Along with the hominin species that we find, we want to understand what kind of world it lived in. We try to recreate the ecology.

* human ancestors had many predators, including crocodiles CSI: Olduvai Gorge. The work of Jackson Njau [scroll through the different pages]

Read Dennis O'Neil's intro to climate change and hominin evolution

* Climate change and paleoanthropology

Genetics gives us two major lines of evidence, existing and ancient. Our own DNA gives us many clues to our evolution. We can compare ourselves to other living primates, and other humans, and the differences will suggest pathways to evolution. Ancient DNA has only been found in the most recent hominins

* review of molecular paleontology

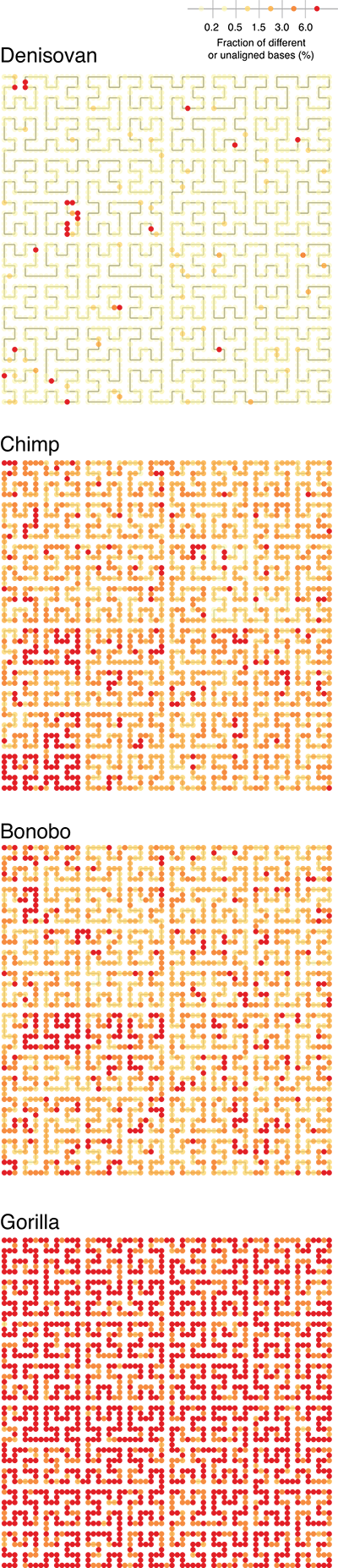

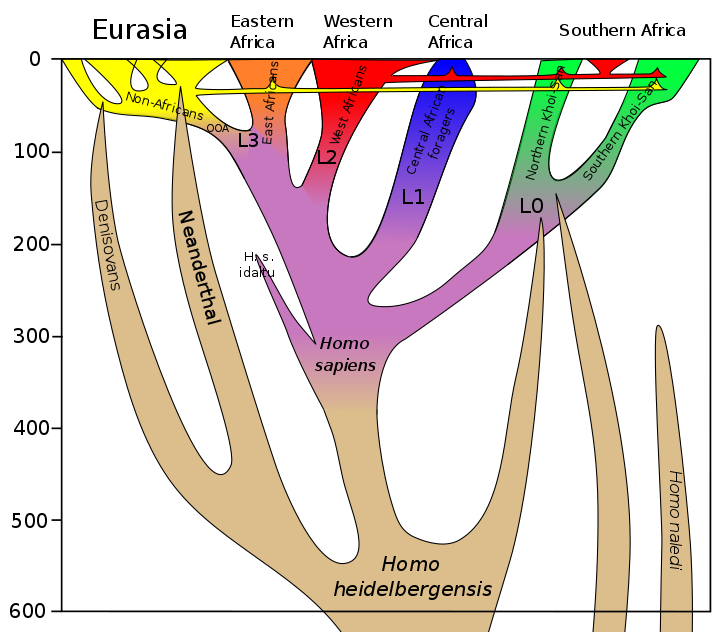

In several recent hominins (such as Neandertals and Denisovans), DNA is preserved, and we can see more than just the skeleton. The DNA tells us what proteins were produced and hints at soft tissue and behavior. The graphic below shows our genetic similarity to Denisovans, chimps, bonobos, and gorillas. The lighter the color, the more genetic similarity to humans; the darker the color, the more genetic distance.

Figure 6.10 using * Hilbert curves to compare the genetic distance to Homo sapiens by Martin Krzywinski / Canada's Michael Smith Genome Sciences Center © 2014

* article on genetic evidence for the difference in brain size between humans and other apes

* no bones, just the dirt; article on recovering Neandertal and Denisovan DNA from Pleistocene sediments

Linnaeus put all life into a huge family tree and correctly included humans on the primate branch. One of the goals of paleoanthropology is to fill-in as many details as possible for all the twists and turns of how that branch leads to us. The family tree metaphor can sometimes be misleading, Stephen J. Gould described taxonomy as more of "luxuriant bush", but for this introductory class, it is useful to minimize the groupings, so we don't get overwhelmed. When paleoanthropologist find a fossil they try to fit it into the existing taxonomy, and there two broad strategies: 1) if you call it another example of an existing group, you are a "lumper" (you're lumping them all together) or 2) if you call it a brand new species you are a "splitter" (you're splitting the branch into two). Splitters tend to get more attention on the news, but for this class we'll lean towards lumping hominin fossils into fewer manageable groups: pre-australopithecines, australopithecines, the genus Paranthropus, early genus Homo, later genus Homo, anatomically modern Homo sapiens (us).

Figure 6.11 "The Hominin Tree of Life" by Katy Wiedemann (used in * The Origins of Humans is Surprisingly Complicated 8-19-14) © 2014

Now is a good time to revisit the taxonomies we looked at in Section 4:

Figure 4.12 * Reed DL, Smith VS, Hammond SL, Rogers AR, et al. (2004) Genetic Analysis of Lice Supports Direct Contact between Modern and Archaic Humans. PLoS Biol 2(11) (CC BY 4.0)

Figure 4.13 "Homo lineage 2017 update" based on * Stringer, C. (2012). "What makes a modern human". Nature 485 (7396): 33–35. by Conquistador, Dbachmann via Wikimedia (CC BY 4.0)

Figure 4.14 Extension to 600 kya (Homo sapiens). 2018 by Dbachmann via Wikimedia (CC BY 4.0)

Vocabulary for 6.1-6.2

Imagination Questions

Encephalization

Visit https://africanfossils.org and compare Paranthropus boisei (KMN ER 406) with Homo habilis (KNM ER 1813), and if it isn't working just take a quick tour of the lab.

For lack of a better name, we can define this group as primate fossils that date before the known group of australopiths, that show evidence of bipedalism, or dentition similar to later hominins who show bipedalism.

One of the major frustrations of paleoanthropology is that this represents a huge time period, and we're trying to answer some of the most important questions of hominin evolution centering around our coming down from the trees with just a handful of fossils.

read Dennis O'Neil's Early Hominins

Australopithecines currently come in two flavors, gracile and robust.

australopithecines = australopiths

The robust australopithecines were re-grouped into a separate genus, Paranthropus, because they are so different from the hominins that came after them.

READ Dennis O'Neil on australopithecine vs. paranthropoid species

Gracile australopiths have a wide range of dates and can be grouped into several species.

Explore Lucy's Story at the Arizona State University Institute of Human Origins

Kenyanthropus platyops is another hominin around the time of Lucy often lumped into the australopithecines.

Explore the 3D model of Kenyanthropus platyops (KNM WT 40000).

We've had problems figuring out where to put the robust australopiths in our family tree. Kind of like that distant cousin that you have to invite to the wedding but can't find a seat for. They are bipedal, so they are definitely closer to us than bonobos, chimps or gorillas, and they have many morphological similarities to other australopiths. But they look much different, with huge mandibles and molars, and a big muscle-head (sagittal crest) like the rest of the great apes. They were nicknamed "Nutcracker Man" because of the huge mandibles, and there is probably some truth to that because we can tell from their teeth and jaws that they had a hard diet or did a lot of chewing. So far, we haven't found any stone tools associated with them. The robust australopiths have had their genus renamed a few times, from Titanohomo, Zinjanthropus, to Australopithecus, and now most paleoanthropologists have settled on Paranthropus.

* article using current Baboon diets to suggest that Paranthropus ate mostly grasses and sedges

We originally defined the genus Homo because of two interrelated factors: the first evidence for stone tools and significantly bigger brains.

READ Dennis O'Neil on early genus Homo

Homo habilis is the first set of fossils to be so similar to us that they were assigned our same genus: Homo. The habilis was named for the dexterity and ability required to make stone tools. Their brains were about a third bigger than australopiths too, and we correlate bigger brains with better tools.

Imagine an awards ceremony at the end of the universe, judging all the hominins that have ever existed, "...and for the most successful hominin... " and then our hopes are dashed as Homo erectus takes the stage, with a big prognathic smile from its parallel dental arcade, jabbing an Acheulian hand axe towards the sky in a triumphant gesture.

Homo erectus is significant for many reasons, but one of the most important is because unlike so many contested hominin paleospecies, we have found so many Homo erectus that almost all paleoanthropologists agree that there was such a thing. Homo erectus was important for its longevity, more than any other hominin so far. It will take us another million years to beat their record, and many scientists are predicting that we don't make it.

Homo erectus was also important as the first documented hominin to leave Africa, and they definitely got around, because their geographical range covers Africa, Europe and Asia (but not Australia or the Americas). Homo erectus begins the human trend of globalization and makes migration (gene flow) one of the important evolutionary forces for humans.

Homo erectus begins in Africa and then emigrates. The Homo erectus found in African shortly after 2 mya tend to more gracile, and many paleoanthropologists have found enough differences from Eurasian Homo erectus to warrant another species name: Homo ergaster. You can think of Homo ergaster as a gracile, African, Homo erectus.

* a range of hominins from different periods have been found at Lake Turkana in Northern Kenya

* Eugene Dubois found the first Homo erectus on the island of Java in Indonesia.

* Classic Zhoukoudian fossils were found near Beijing, and they were originally sold in apothecary shops as "dragon bones".

* article on very early Homo erectus in China

* Tautavel man from Arago Cave

The Dmanisi fossils are special for how old they are (1.77 mya), how small they were, how small their brains are, and how simple their tools are, and that they're found in Europe. The old theory is that Homo erectus was the first hominin to leave Africa, enabled by their large overall size, large brains, and complex tools. But, the Georgian hominins were small, had small brains, and used simple tools, they were similar to australopithecines in many ways.

* article on Skull 5: variations within the Dmanisi suggest that all hominins can be lumped into Homo erectus

* article on Dmanisi toothpick use

We want to ask what kind of intelligence is required to work stone with this amount of symmetry and precision?

.png)

Figure 6.18 Lanceolate (lance-shaped) hand axe from the Acheulean site of San Isidro, Madrid, Spain. Hugo Obermaier (1925): El Hombre fósil. Madrid (public domain)

Almost all paleoanthropologists acknowledge Homo erectus as a category of hominin in between Australopithecines and anatomically modern Homo sapiens. The transition from Homo erectus to Homo sapiens is less clear. Extreme lumpers consider Homo erectus as the beginning of a single chronospecies that leads to us, extreme splitters have dozens of species designation for different sets of fossils based on their time, region, and morphology.

A hominin found in Europe from around 1.2 mya to 800,000 ya, with a morphology very similar to Homo ergaster.

* Article on Homo antecessor dentition

Dennis O'Neil on Homo heidelbergensis

vocabulary

Imagination Questions

The animal rights movement has contributed to politicizing the human diet. Paleoanthropological evidence can be used to support both veganism and raw steaks. Would scientific evidence about our evolutionary propensity for a certain diet effect what you eat?

Figure 6.19 arguing for a vegan diet by Choose Hope for the Animals ©2014 (permission pending)

For the hominins in the last section, paleoanthropology hasn't settled on a single name, so it gets a little confusing. Some lumpers just call them all "humans", some splitters come up with taxonomies of dozens of species. There are different ways to group these hominins: by geological period, glacial period, tools (from broad lithic periods to the more specific archaeological industries), and names of paleospecies (mostly based on bone morphology), and they don't always fall in neat categories. This means that weather, tools, and osteology don't always go together.

The Pleistocene is defined by repeated events of glacial advance and retreat, which meant radical weather changes. Geologists have pushed the boundary between the Pliocene and the Pleistocene back to 2.5 mya to account for new data on early glacial periods. This date happens to fit pretty well with the first stone tools found, and hence our definition of the genus Homo. Section 6.9 focuses on hominins in the Middle Pleistocene, especially the transition from Homo erectus to the very noncommittal term "Premodern Humans". The "human" part acknowledges that they were a lot like us. The "premodern" part recognizes that there are enough differences in their bone morphology and cultural attributes to question whether they had a mind different enough to think of ourselves as different from them. I'm not sure myself. A famous paleoanthropologist said that if a Homo erectus sat down next to you on a bus you might want to change seats, but if it were a Neandertal (a kind of European Middle Pleistocene hominin) you just might stare a little. We'll continue this kind of "us" or "them" debate into the next section.

Some of the most fascinating recent research are the advances in decoding the Neandertal genome, especially that some were redheads and had an allele (FOXP2) involved with language. You will definitely hear more details about this in your lifetime.

Read Dennis O'Neil's intro to Neandertals

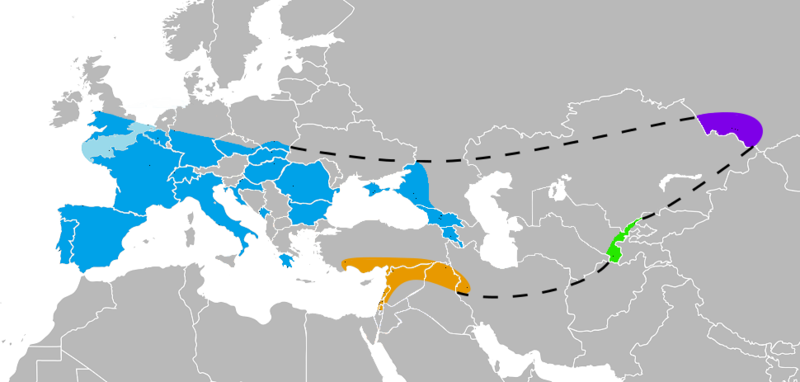

Figure 6.20 Known Neanderthal range in Europe (blue), Southwest Asia (orange), Uzbekistan (green), and the Altai mountains (violet), as inferred by their skeletal remains (not stone tools) by Nilenbert, Nicolas Perrault III (GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Figure 6.21 * Humans from La Chapelle aux Saints [in French] by Emmanuel Roudier © 2010

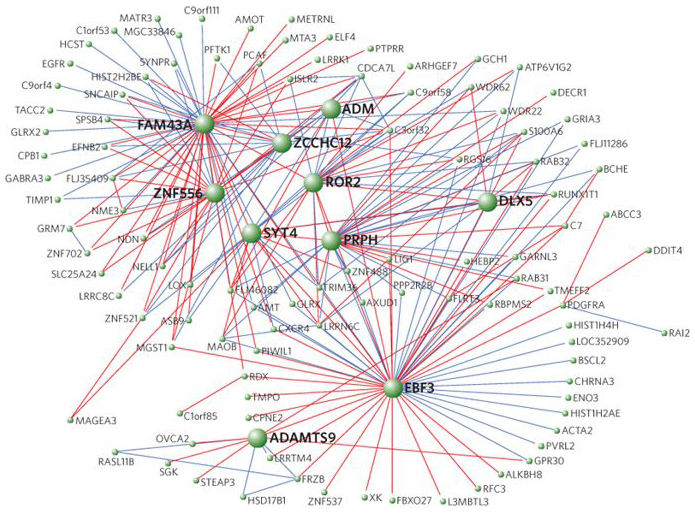

Figure 6.22 "Visualization of one of the modules containing FOXP2 and FOXP2 chimp differentially expressed genes." in Genevieve Konopka, et al. "Human-specific transcriptional regulation of CNS development genes by FOXP2" Nature volume 462, pages 213–217 (12 November 2009) © 2009

* FOXP2 network, a neural network in modern Homo sapiens brains also found in Neandertals.

* a good introduction to Neandertals by Svante Pääbo, one of the scientists responsible for working out the Neandertal genome

* Read the first 5 pages of this article on Bone tools made by Neandertals What is a lissoir? What was it used for? How do the archaeologists know that it is a tool and not just food remains?

* article on Neandertals eating pigeons a good example of the range of foods that hominins were exploiting.

* article showing the major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neanderthals

Mousterian is a tool industry associated with Neandertals.

Chatelperronian is a tool industry used by Neandertals.

Figure 6.23 Chatelperronian blades (Public Domain)

Our fascination with Neandertals in popular culture reflects many of the paleoanthropological debates of our relation to Neandertals. Are they us? Are we them? Is there something in between our philosophical categories of Man and Beast?

Figure 6.24 "Flintstones Cartoon Characters Names Drawing" by pixy.org (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

A playlist of music and standup comedy from around the world about Neandertals:

Figure 6.25 The Croods by DreamWorks ©2013 (fair use)

A blog about how we depict hominins:

April 11, 2012/in Comics, Evolution /

Have you ever noticed that almost all artist renderings of ancient hominins are dudes? There were other non-man cave people, you know. I am here today to correct this imbalance.

Let's first even out the gender ratio here.

That's better. She is woman. She is cave. She has a great zebra print top. And I'm not done yet. There are other subgroups that need representation.

and

Cave-people-equal-representation problem solved. You're welcome.

Figure 6.26 "Lesser Known Cave People" by Beatrice the Biologist ©2012

We use neandertals as a symbol of our past.

The Denisovans are another group of hominins that most group as a kind of Homo sapiens. They have a combination of big teeth, which we usually associate with older hominins, but some complex tools and symbolic behavior that we associate with anatomically modern Homo sapiens.

read this Nat Geo intro to Denisovan DNA

* another overview of Denisovans

* genes found in Tibetans that help them survive high altitude shared with Denisovans

Wow! San Diego is on the map as a game changer in hominin evolution! Evidence that 130,000 years ago, someone cracked open the bones of mastodons with hammerstones.

Visit the San Diego Natural History museum's exhibit.

Why were they breaking bones? To get to the marrow? To shape the bone into other tools?

Who were they? Homo sapiens? a middle Pleistocene hominin? Homo erectus? We didn't find any remains of the people using the tools, so we wait on future discoveries.

Most evidence points to the first settlement of the Americas reliably at 15,000 years ago, or possibly as old as 30,000. But this find is so much earlier, 130,000 years ago, it really is a game changer.

Homo floresiensis is a hominin found on Flores island in Indonesia that lived around 50,000 years ago. It is unusual for its overall small size and small brain size, and very recent dates. Because of its small size it has been nicknamed the "hobbit".

* an explanation from 2014 of the questions about Homo floresiensis

Scientists often use Law of Parsimony (Occam's Razor or the Keep It Simple, Stupid principle) to interpret limited data. So, since Homo floresiensis co-existed with both Homo erectus and anatomically modern Homo sapiens, an early research question was whether Homo floresiensis were descended directly from Homo erectus or if they are within the range of variation of Homo sapiens.

But, recent evidence suggests the last common ancestor with Homo floresiensis may be much earlier, closer to Homo habilis than to either H. erectus or H. sapiens.

* research from 2017 suggesting Homo floresiensis may be a sister species to Homo habilis

One of the arguments to include them as a variation of Homo sapiens is the numerous examples of animals with smaller versions on islands. Here on the Channel Islands we find fossils of pygmy mammoths that were about the size of a pony, and we still find today a species of pygmy fox. This could help explain the small stature of Homo floresiensis.

* read about insular dwarfism

Homo naledi is an amazingly large number of hominin fossils found in a cave in South Africa. The dates haven't been determined but the morphology shows fairly small brains compared to the development of their lower bodies. Also amazing is the difficult of getting bodies to the location, which implies the cultural practice of burial.

* Original article on Homo naledi

* the geological and taphonomic context

The phrase "anatomically modern Homo sapiens" is the scientific consensus for the group of hominin skeletons that everyone agrees to call "us".

Chris Stringer talk, watch the first 18 minutes

This is the end of paleoanthropology section. It brings us up to what most scientists agree is all the same species as what we are now, with no significant biological differences. There are obviously cultural differences, and you can study those if you take the Introduction to Archaeology class, but when scientists say "anatomically modern", they are saying that these hominins are biologically the same as us, and excuse the science fiction scenario, but if you somehow extracted enough DNA from one of these anatomically modern Homo sapiens bones found around 100,000 ya, cloned it, raised it in a typical family, he or she would end up an indistinguishable member of our society.

When reading about the different models for recent human origins, you continually need to be asking yourself the question: "What is the evidence that supports this model?" Get into the nitty-gritty details. Don't worry that there is conflicting evidence, that's OK, in fact, that's typical of science. We try to keep an open mind and see both sides of an issue; it's ok to hold multiple hypotheses. This is similar to the idea I mentioned the Anthropological Imagination where anthropologists are skeptical of unicausal explanations. More evidence comes from the DNA of at least three groups of Neandertals, and another coexisting group, the Denosovans.

Even though this debate has been pretty much resolved, it is still a good example of the scientific process and complex and varied forms of evidence that anthropologists use to answer questions.

Figure 125 results from Arnie Schoenberg's Genographic test Arnie Schoenberg/National Geographic © 2013 (fair use)

skim Dennis O'Neil on the origins of modern humans

* watch Svante Pääbo talk about Neandertal DNA

We are still debating how much genetic material the regional continuity of hominins contributing to our modern DNA, but we don't think it's very much. We mostly come from Africa very recently. The genetic evidence points to a bottleneck event between around 50,000 to 100,000 years ago for everyone who left Africa. Genetic Drift made all non-Africans extremely homogeneous.

To get a sense of the Upper Paleolithic revolution try taking some of the virtual tours available for the cave art, e.g. Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave.

Also, compare the Lower Paleolithic and Middle Paleolithic to the Upper Paleolithic. Count how many years it takes for people to invent a way of making stone tools so different from before that it justifies a new name for the assemblage.

* Watch the movie: Cave of Forgotten Dreams Werner Herzog, 2010:

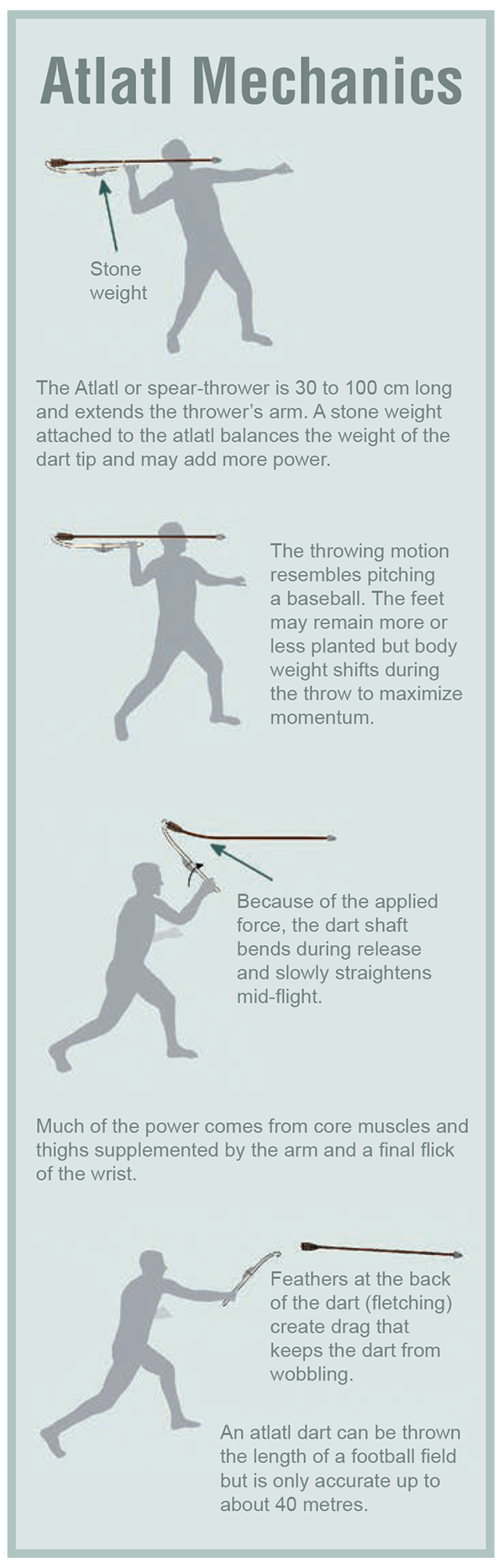

Figure 6.29 Atlatl Mechanics by Todd Kristensen from * "Alberta's Record of Ancient Atlatl Hunting" by Todd Kristensen, Brian Vivian, and Colleen Haukaas in Alberta Outdoorsmen, October ©2017

* an author searches for the origin of consciousness

Paleoanthropology usually stops at around the Upper Paleolithic, and you would normally take an archaeology class to learn about more recent humans, and their recent inventions like ceramics, agriculture, metal, cities, etc.

* Ötzi the Iceman (5,000 ya in the alps)

* an update on Kennewick Man (9,000 ya in Washington state)

Vocabulary for 6.13

Draw a genealogical chart of your family and expand it to include the three taxonomies we've seen in this class:

At each juncture, give the approximate date when that individual was born, or the last common ancestor between the two groups of species existed.

Why an Atlatl Works

Figure 6.30 "Atlatl Lessons" by Janice Cotcher, Math Central, University of Regina © 2019

When we talk about speed, we usually refer to linear velocity or the speed as an object travels in a straight line. The path of the dart is not linear while it is in the thrower's hands -- it is approximately circular. Angular velocity is the speed in a circular motion or through an angle -- it is commonly measured in radians per second. Radians are a measure of a portion of the circumference along a circle with radius of 1 unit so one revolution is 2π. The relationship between linear and angular velocities is as follows:velocity=radius x angular velocity

v = r × ω

Distance thrown is dependent upon the speed, the angle, and the height of release of the dart. An atlatl allows a human to throw faster and further by "extending" the throwing arm. For example, say a person with 0.68 m long arm can throw a dart at 6.5 revolutions/sec (about 34.9 rad/sec):

v = 0.68m x 13π rad/sec = 27.8 m/s =100.0 km/h

[from "Atlatl Lessons"by Janice Cotcher, Math Central, University of Regina © 2019]

If the same person used a 2 foot (0.61m) atlatl (see the figure above), what would the linear of speed of the dart be? How much faster would they throw the dart with the atlatl?

previous section: 5 primatology

next section: 7 human variation

problems (mistakes, bad links, etc.)